Eastern King Prawn – New South Wales Ocean Trawl Fishery

Assessment Summary

Eastern King Prawn

Unit of Assessment

Product Name: Eastern King Prawn

Species: Melicertus plebejus

Stock: Eastern King Prawn – Eastern Australia

Gear type: Otter Trawl

Fishery: NSW Ocean Trawl Fishery

Year of Assessment: 2017

Fishery Overview

The Ocean Trawl Fishery can be divided into two sectors, the Ocean Fish Trawl and the Ocean Prawn Trawl Fisheries. Although the two forms of trawling target different species and are different in operation, they take many common species and have a significant level of geographic overlap (NSW DPI, 2007). The non-selective nature of trawl nets, and the broad range of substrates over which trawling occurs, results in a large number of finfish and shellfish species being taken. The major species targeted by ocean prawn trawlers vary with the depth of fishing, and include Eastern King Prawn, Eastern School Prawns and Royal Red prawns, and Eastern School Whiting. Fish trawling mainly targets species such as Silver Trevally, Tiger Flathead, Southern Calamari, Eastern School Whiting and a number of shark and ray species (NSW DPI, 2007). The prawn sector can be divided further into three sub-fisheries:

- Inshore prawn trawl, which uses otter trawl gear to target prawns within 3nm of the coast;

- Offshore prawn trawl, which uses otter trawl gear to target prawns from waters outside 3 nautical miles and west of the 280 metre (150 fathom) depth contour; and

- Deepwater prawn trawl, which uses otter trawl gear to target prawns east of the 280 metre (150 fathom) depth contour.

The inshore and offshore sectors generally target Eastern King Prawns, with the offshore sector operating out to the edge of the continental shelf (approximately 230 m). The deepwater prawn sector targets species of deepwater prawns, such as Royal Red Prawns, at depths in excess of 310 m (Macbeth et al. 2008). The fish trawl sector can also be further divided into two sub-fisheries:

- The Fish (northern zone) fishery, is authorised to take fish using an otter trawl net (fish) or a Danish seine trawl net (fish) from ocean waters north of Barrenjoey Headland (latitude 33°35′ south).

- The Southern Fish Trawl sector is authorised to take fish (other than prawns) using an otter trawl net (fish) or a Danish seine trawl net (fish) from ocean waters inside 3 nautical miles and south of Barrenjoey Headland.

Trawlers off NSW catch four of the eight known species of Ibacus, collectively marketed as ‘Balmain Bugs.’Commercial catch statistics do not differentiate between the four species, but 90% of the catch taken while vessels are targeting Eastern King Prawn is Smooth Bug (Haddy et al., 2007).

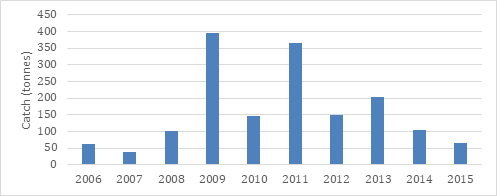

Figure 1 Catch trends

Risk Scores

|

Performance Indicator |

Risk Score |

|

MEDIUM |

|

|

1A: Stock Status |

LOW |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

LOW |

|

C2 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF FISHING |

MEDIUM |

|

MEDIUM |

|

|

2B: ETP Species |

MEDIUM |

|

2C: Habitats |

MEDIUM |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

MEDIUM |

|

C3 MANAGEMENT |

MEDIUM |

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

MEDIUM |

Summary of main issues

- The most recent stock assessment of Eastern King Prawn indicates the stock is fluctuating at or around levels consistent with MSY, however there is considerable effort latency in both the Qld and NSW trawl sectors which harvest this shared cross-jurisdictional stock. Current active effort levels are sustainable although they are influenced more by economic constraints than effective effort or catch controls. It is not clear whether the existing harvest strategy is sufficient to maintain stocks at productive levels should economic circumstances change;

- There are no well-defined harvest control rules in the fishery which would serve to reduce exploitation as the point of recruitment impairment is approached;

- The information available on discard and ETP species interactions in the fishery is relatively limited and there has been no ongoing independent, spatially representative monitoring of the fishery;

- The information base to support assessments of habitat impacts from the fishery is limited compared to other trawl fisheries in Australia and internationally. Detailed mapping and habitat classification of the NSW continental shelf has recently been undertaken, though there appears to be only limited information on the fine scale spatial distribution of effort in the fishery, particularly overlayed against potentially vulnerable habitat types.

Outlook

| Component | Outlook | Comments |

| Target species | Improving ↑ | The harvest strategy in both main fisheries (ECOTF, OTF) is expected to be strengthened in the coming few years. In the OTF, the NSW Government has implemented a Commercial Fisheries Business Adjustment Program which will reduce excess harvesting capacity by increasing minimum shareholdings with a plan to introduce ITEs in the Inshore and Offshore Prawn share classes by end 2018. In the ECOTF, harvest strategies with well-defined harvest control rules will be developed by 2018 as part of the Queensland Government’s Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027. |

| Environmental impact of fishing | Stable = | No major changes are expected to Component 2 PIs. |

| Management system | Improving ↑ | Reforms being implemented through the Commercial Fisheries Business Adjustment Program may lead to a reduction in some risk scoring, if there is stronger evidence of regular internal management system review and higher rates of compliance. |

COMPONENT 1: Target species

1A: Stock Status

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing.

| (a) Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

Eastern King Prawn (Melicertus plebejus) is endemic to Australia. Eastern King Prawn occurs on the eastern Australian coast between Hayman Island in Queensland and north-eastern Tasmania (20–42°S respectively), and the species exhibit strong stock connectivity throughout their range. Eastern King Prawns are harvested in Queensland and New South Wales fisheries, and are considered a single multi-jurisdictional biological stock (Prosser and Taylor, 2016). This assessment examines the status of the Eastern Australian biological stock.

Prosser and Taylor (2016; and references therein) report that the most recent assessment estimates that biomass in 2010 was 60–80 per cent of the unfished 1958 levels. The assessment developed minimum monthly catch rate reference points that imply levels of biomass would be sufficient to sustain catches of MSY in each fishery region. For the Queensland component of the stock, standardised monthly regional catch rates were mostly above MSY catch rate reference points between 2009 and 2015, indicating the level of biomass was sufficient to sustain catches at MSY. For the New South Wales component of the stock, the median nominal commercial catch rates were relatively stable between 2012 and 2015, and slightly greater than catch rates prior to 2012, indicating stable or increased abundance. Fishery-independent surveys of recruit abundance show variable recruitment to the fishery with no discernible trend over 10 years, with peaks in 2008 and 2012. Recruitment in most prawn species is thought to be environmentally influenced. Based on the above, Prosser and Taylor (2016) conclude that the stock is unlikely to be recruitment overfished.

The high estimated ratio of current to unfished biomass is evidence the stock is highly likely to be above the point of recruitment impairment (PRI) and probably fluctuating at or around levels capable of producing MSY.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

1B: Harvest Strategy

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place.

| (a) Harvest Strategy |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

Despite the broad distribution of Eastern King Prawn, all sources of mortality are well understood and estimates of catch are available for all sectors. Catch is split approximately 80:20 between Queensland (where the main adult habitats are) and NSW (where the major recruitment grounds are) (O’Neill et al., 2014).

The main fishery for Eastern King Prawn in Queensland is the East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery (ECOTF). The main elements of the harvest strategy for the QECOTF include:

- Limited entry through a requirement to hold a Commercial Fishing Boat License (FBL), as well as limited entry into the various sub-components of the fishery through the allocation of fishery symbols (T1, T2, M1 and M2);

- Limits on the Total Allowable Effort (TAE) in the ECOTF, allocated to each license holder as tradable ‘effort units’. The combination of effort units held and the size of the vessel determine the number of fishing days each operator can work (larger vessels require more effort units to fish one day than small vessels);

- Gear and mesh restrictions;

- Vessel hull size restrictions;

- Spatial and temporal closures, including the closures associated with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan;

- Vessel horse power restrictions;

- Daily catch and effort reporting;

- Monitoring effort usage through VMS;

- Periodic assessment of stock status for key species.

Although the ECOTF is currently effort limited with a cap on effort of 5% less than 1996 levels, a key weakness in the harvest strategy is the existence of substantial latent effort, despite licence buybacks in 2001 and 2005. In 2016, there were a total of 2.75 million effort units for the East Coast and 73,387 effort units for T2 (Concessional) licenses of which 64% and 27% respectively were utilised (DAF, 2017a). At present, there are few mechanisms to prevent reactivation of this latent effort, or to manage effort shifts within the fishery (either geographically or across different target species). Overall effort in each sector is influenced more by economics that any effective catch or effort constraint. There are no well-defined harvest control rules for any of the main target species which serve to reduce effort as the PRI is approached.

The Queensland Government has recently announced the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027 which commits amongst other things to the adoption of harvest strategies for all major fisheries by the end of 2020, with a priority to develop trawl, crab and inshore fisheries harvest strategies by the end of 2018 (DAF, 2017b). It is intended that harvest strategies will include well-defined harvest control rules that aim to maintain stocks at levels above MSY.

In NSW, catches are primarily taken in the Offshore Trawl Fishery (OTF). The main measures in the harvest strategy include:

- Limited entry;

- Gear and mesh restrictions;

- Spatial zoning;

- Spatial and temporal closures;

- Daily catch and effort reporting;

- A Fishery Management System (FMS) that requires a recovery strategy to be implemented if the fishery status is assessed as ‘overfished’ or ‘recruitment overfished’[1];

- Periodic assessments of stock status.

Limited entry is implemented through a share management scheme under which access to the fishery is limited to shareholders or their nominated fishers who hold sufficient shares to satisfy the minimum shareholding levels established for each share class in the Fisheries Management (Ocean Trawl Share Management Plan) Regulation 2006 (the OT SMP) (NSW DPI, 2011). There are two main share classes relevant to the harvest of Eastern King Prawns:

- Inshore prawn trawl, which allows for the take of ‘fish’ using an otter trawl net (prawns) from inshore waters (inside 3 nautical miles); and

- Offshore prawn trawl, which allows for the take of ‘fish’ using an otter trawl net (prawns) from offshore waters (outside 3 nautical miles) that are west of the 280 metre (150 fathom) depth contour.

There has been some consolidation in the number of shareholders in both sectors (e.g. DPI, 2011), however Stevens et al (2012) reported considerable levels of excess harvesting capacity (latent effort) in the OTF. For example, in the inshore Ocean Trawl Fishery – prawn trawl sector, 48 out of 199 shareholders accounted for 95% of the catch (or 76% latency).

Latency across the commercial fishing sector is being addressed through a Commercial Fisheries Business Adjustment Program (the BAP) which aims to link shares to either catch or fishing effort, provide assistance to fishing business to adjust their operations and streamline current fishing controls that impact fishing efficiency[2]. In the OTF, all shareholders in the Inshore and Offshore Trawl fisheries must hold a minimum of 50 shares by December 2017. In addition, an effort quota (in the form of transferable hull unit days) will commence by end 2018[3].

Using a spatially structured stock assessment model covering six separate regions of the fishery across Queensland and NSW, O’Neill et al. (2014) estimated Eastern King Prawn MSY at 3100t (95% c.i. 2454–3612 t). The 2015 catch was 2892 t (2363 t in Queensland; 529 t in New South Wales), which is below the estimate of MSY. The average catch in 2013–15 was 3135 t, which is slightly above the estimate of MSY.

Prosser and Taylor (2016) report that the most recent assessment estimates effort (E) at MSY (EMSY), standardised to the number of boat-days in 2010, as 38,002 boat-days (95% c.i. 27,035–50,754 boat-days) assuming no further increase in fishing power or costs. An alternative estimate of 28,300 boat-days (95% c.i. 20,110–37,663 boat-days) accounts for a three per cent per year increase in fishing power over the next decade and costs from 2010 levels. Effort in 2015 was 20,076 boat-days (14,688 boat-days in Queensland; 5,388 boat-days in New South Wales), which was well below both estimates of EMSY and the peak effort of around 30,000 boat-days in 2000, but similar to levels in 2013. However, the decline in effort since 2000 has been offset by increases in fishing power. The number of boats accessing the fishery has remained stable in Queensland since 2013, but has continued to decline in New South Wales.

Unlike many other species targeted in the ECOTF, the proportion of the stock protected by closures in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) is very low and the level of protection afforded by other closures (e.g. State marine parks, closures under the Fisheries Act) has not been reported. An effort cap for the Southern Trawl Fishery area is in place which, if exceeded, limits each license to no more than 24 trawl fishing days per month for the months May, June and July. The intent of this measure is to maintain effort at levels consistent with EMSY estimated by Courtney et al (2014). Nevertheless, the extent to which this measure can effectively limit overall effort is unclear because (a) days are likely to be lost each month through bad weather anyway and (b) there is nothing to prevent latent or active licences entering the fishery in years when the rule is triggered.

While the Eastern King Prawn stock is currently being fished at levels consistent with maintaining the stock at or above BMSY, this appears to be largely due to economic constraints rather than harvest controls which actively limit exploitation to sustainable levels. Considerable capacity for additional fishing mortality currently exists within the fishery and it is not clear that existing harvest strategy arrangements are sufficient to achieve the stock management objectives in criterion 1A(i) if economic circumstances should change. The Eastern King Prawn stock does not appear to have the same ‘safety nets’ afforded by spatial closures as some other stocks. Accordingly, this SI has been scored precautionary high risk. Future scoring of this SI should take into account progress towards management reforms in both jurisdictions.

[1] The FMS notes that “‘Overfishing’ occurs when fishing mortality is much greater than natural mortality and indices of stock abundance have declined. ‘Recruitment overfishing’ is used to describe cases where the fishing pressure has reduced the spawning stock to such a low level that recruitment is significantly affected.”

[2] http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/commercial/reform

[3] http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/commercial/reform/decisions/ot-inshore-offshore

| (b) Shark-finning |

|

|

NA – only scored if the target species is a shark.

CRITERIA: (ii) There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place.

| (a) HCR Design and application | ||

| Eastern King Prawn |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

There are currently no well-defined HCRs in the OTF harvest strategy which require a reduction in exploitation as the PRI is approached. There are some ‘in house’ trigger points used in the annual stock assessment workshops such as presence of a certain number of age classes indicating health of spawning stock or an approximation of recruitment, but these are not publicly available. The FMS and SMP set out a framework of trigger points against prescribed goals and performance indicators, but action to review exploitation of primary species is triggered only after a species is declared ‘overfished’ or ‘recruitment overfished’, rather than before the stock reaches PRI. Stock status is assessed periodically according to the Framework for the Assessment of Harvested Fish Resources in NSW (Scandol, 2004).

In the ECOTF, there are currently no well-defined HCRs which set out pre-agreed measures to limit exploitation as the PRI is approached. The best approximation of a HCR in the fishery was the Performance Management System (PMS) which established trigger points, which if breached, triggered a review of available data and management arrangements if required (QG, 2009). Nevertheless, use of the PMS has been largely discontinued, with the most recent report available from 2012 (DEEDI, 2012). There is also evidence from other key target stocks within the ECOTF that existing arrangements have not served to reduce exploitation as the PRI is approached (e.g. saucer scallops; Kangas and Zeller, 2016). Accordingly, it not clear that generally understood HCRs are in place that are expected to reduce exploitation as PRI is approached.

Notwithstanding that, stock monitoring in recent years has detected no evidence of recruitment overfishing for Eastern King Prawns and effort levels are at very low levels historically. Accordingly, we have scored this SI precautionary high risk. The Queensland Government has recently committed to the development of a harvest strategy with well-defined HCRs for the ECOTF by the end of 2018 (DAF, 2017b).

PI SCORE – PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK

1C: Information and Assessment

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy.

| (a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|

Stock structure for Eastern King Prawn is well understood including areas of recruitment, distribution and movement in both New South Wales and Queensland. The biology of this species is also well understood (e.g. Courtney et al. 1995; Courtney et al. 1996; Lloyd-Jones et al. 2012). There are extensive catch and effort records from various fisheries in both states, and these have been used to develop a bio-economic model that provides appropriate measures such as effort at MSY and effort at MEY to support the harvest strategy and potential harvest control rules (Courtney et al, 2014; O’Neill et al, 2014). Also, fleet dynamics for the fishery are understood (including VMS data for the ECOTF), with estimates of vessel power previously published (O’Neill and Leigh, 2007).

| (b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

LOW RISK |

|

In the Eastern King Prawn sector, removals from the stock by commercial fisheries are monitored through compulsory catch and effort logbooks, while recreational catches are periodically estimated (e.g. West et al, 2016). Fisheries Queensland has routinely monitored stocks using an annual Fishery Independent Trawl (FIT) survey since 2006[1]. The FIT survey is conducted in key juvenile Eastern King Prawn habitats in southern Queensland waters during the peak recruitment period for the species (November and December). The index of abundance of recruit Eastern King Prawn produced by the survey is combined with other available fishery data to assess the status of the stock annually. These survey results, combined with standardised commercial catch rates and periodic stock assessments (e.g. O’Neill et al, 2014), are sufficient to support an effective HCR for the stock.

[1] https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/fisheries/monitoring-our-fisheries/commercial-fisheries/species-specific-programs/monitoring-reporting/eastern-king-prawn-update

| (a) Stock assessment |

LOW RISK |

|

O’Neill et al. (2014) provide a comprehensive bioeconomic model for EKP that simultaneously assesses six different regions across Queensland and NSW and provided several different management strategy evaluations. The model estimates biomass relative to the reference year 1958 when data and catch history were first available, and produced estimates of MSY and effort at both MSY and Maximum Economic Yield (MEY). The model is appropriate for the stock and estimates status relative to reference points which are appropriate and can be estimated.

| (b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

LOW RISK |

|

O’Neill et al (2014) accounted for uncertainty in parameters such as stock-recruitment steepness, natural mortality and annual recruitment variation through Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis, as well as alternative model sensitivity runs accounting for different estimates of fishing power. The methodology used and outcomes were published in a peer-reviewed journal.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

2A: Other Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI.

| (a) Main other species stock status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The intent of this scoring issue is to examine the impact of the fishery on ‘main’ other species taken while harvesting the target species. ‘Main’ is defined as any species which comprises >5% of the total catch (retained species + discards) by weight in the UoA, or >2% if it is a ‘less resilient’ species. The aim is to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired and ensure that, for species below PRI, there are effective measures in place to ensure the fishery does not hinder recovery and rebuilding.

The OTF Prawn Fishery encompasses multiple bioregions, gear types and target grounds. As a result, the composition of other species taken in the fishery varies both spatially and temporally (e.g. Macbeth et al, 2008). Previous studies have shown that the fishery interacts with a very large number of species, most of which occur only very infrequently in trawls (e.g. Kennelly et al, 1998; Macbeth et al, 2008). The OTF FMS lists other main species as: Eastern School Prawn, Royal Red Prawn, Octopus, Cuttlefish (Sepia spp.), Southern Calamari, Tiger Flathead, Sand Flathead, Silver Trevally and Fiddler Shark. However, the last five species are probably more targeted by the OTF Fish Trawl Fishery.

There are few recent published estimates of the species composition of discards for the various sectors of the OTF, so two different information sources have been used to identify main other species taken in the fishery:

- Catch data for retained species reported in logbooks between 2010-11 and 2014-15; and

- Species compositions reported from onboard observer studies (e.g. Kennelly et al, 1998; Macbeth, 2008).

Balmain bugs and Eastern School Whiting have been assessed under Component 1 in the full assessment report. Only Eastern School Prawn (12%) comprised >5% of the retained catch in the Inshore and Offshore Prawn sectors combined during the period 2010-11 to 2014-15. Of the remaining species, Stout Whiting accounted for 3.5% of the retained catch and a group of undifferentiated ‘trawl octopus’ accounted for 6.7% although is likely to be made up of multiple species. Based on this, Eastern School Prawn is assessed here as a main other species based on reported catch data.

Kennelly et al (1998) examined catch composition of the prawn sector in the OTF across four main ports in northern NSW in a two-year observer-based study. They found significant variations in species-specific abundances at all spatial and temporal scales sampled, such that the occurrences and abundances of particular bycatch species depended on the location, season and year examined. In catching an estimated 1,579t of prawns during the two-year survey, oceanic prawn trawlers from the four ports were estimated to have caught approx. 16,435t of bycatch (a bycatch-to-prawn ratio of 10.4:1). Of this bycatch, 2,952t were estimated to have been retained for sale and 13,458t were discarded. Although catch by weight was not reported, the only individual non-prawn species accounting for >5% of the total catch by number (retained + discarded) were stout whiting and Eastern School Whiting (albeit called Red Spot Whiting in the study). The cuttlefish and octopus groups also accounted for >5% of the catch by number, although may have comprised multiple species.

More recently, Macbeth et al (2008) examined the impact of square mesh cod ends on catch composition in the northern part of the OTF in paired comparisons against standard diamond mesh cod ends. While the data in this report is based on catch rate by number of fish rather than weight, there appeared to be no very large discrepancies between the average weights among individual species. Apart from Eastern King Prawns and Eastern School Whiting, other species accounting for >5% of the catch in this study were Eye Gurnard (Lepidotrigla argus) and Longspine Flathead (Platycephalus longispinus). All other species accounted for <5% of the total catch by weight.

On the basis of the two observer studies, we have also assessed here as main other species Stout Whiting, Eye Gurnard and Longspine Flathead, albeit we note that recent evidence of full catch composition in the OTF is limited.

For Eastern School Prawn, Taylor et al (2016) report that the NSW stock of Eastern School Prawn is unlikely to be recruitment overfished. They note that fluctuations in stock abundance appear to be environmentally-driven, rather than driven by the fishery itself, with recent research establishing that environmental factors can have a strong influence on Eastern School Prawn catches. Accordingly, the stock is likely to be above the PRI.

For Stout Whiting, Roy and Hall (2016) report that population modelling conducted in 2014 indicated that biomass was marginally above the biomass that would produce MSY. Accordingly, the stock is highly likely to be above the PRI.

No assessments have been conducted for either Eye Gurnard or Longspine Flathead. Fishbase lists Eye Gurnard as having high resilience with low to moderate vulnerability (Froese and Pauly, 2017). Longspine Flathead is reported as having medium resilience and low to moderate vulnerability. While the status of each species against the PRI is not known, given the relatively productive nature of both species, there is a plausible argument that the measures in place (e.g. vessel/gear limits, BRDs, spatial closures) are at least likely to ensure the fishery does not hinder recovery or rebuilding if necessary. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

Nevertheless, we note the fishery would be better placed against this SI with a more recent estimate of catch and discards composition by weight based on information directly from the fishery, and assessments of likely impact on key non-target species. NSW DPI (2017a) report that observer field work in the fish trawl sector of the OTF has been completed with a final report due in December 2017. In the prawn trawl sector, observer field work commenced in June 2017 incorporating the 2017/18 and 2018/19 fishing seasons.

CRITERIA: (ii) there is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species; and the UoA regularly reviews and implements

| (a) Management strategy in place |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The OTF manages bycatch and byproduct harvest through limiting effort, gear design (e.g. minimum mesh size, including allowances for smaller square mesh cod ends; mandatory bycatch reduction devices), actively trying to reduce effort through the SMP as well as a series of closures (summarised in NSW DPI, 2011). Specific management interventions have been introduced for species of concern (e.g. Gulper Shark[1]; Mulloway[2]).

The FMS also has a specific PI with a trigger for the development of a recovery plan if any byproduct species is assessed as overfished (e.g. Mulloway recovery plan). The FMS also includes triggers for management action if there is a significant change in species composition of catch and if discards in the fishery increases substantially between consecutive observer surveys (NSW DPI, 2007). While these measures are intended to maintain main other species at levels above the PRI, limited and sporadic monitoring of other species catch composition and discard rates means it is difficult for the management agency to assess trends and therefore to have confidence that other species are highly likely to be above PRI. Accordingly, we have scored the fishery medium risk against this SI.

[1] http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/commercial/fisheries/ocean-trawl/gulper-shark

[2] http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/commercial/fisheries/ocean-trawl/managing-the-otf-impact-on-mulloway

| Danish seine – north |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

Danish seining is limited by similar types of measures as those applied in the prawn otter trawl fishery: limited licensing, gear restrictions (e.g. minimum of 83mm mesh throughout the net), spatial closures and other species specific measures (e.g. Mulloway). Given the absence of information on total catch composition, there is little evidence to assess the effectiveness of management measures against the scoring guidelines. Accordingly, we have scored the gear type precautionary high risk against this SI.

(b) Management strategy evaluation

| Otter Trawl – Prawn |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Given the healthy stock status of Eastern School Prawns and Stout Whiting, the relatively productive nature of the other two main other species and observer studies documenting reductions in bycatch through BRDs (e.g. Macbeth et al, 2008), there is a plausible argument that the existing measures are likely to be limiting fishing mortality on other species to levels likely to be above the PRI. Nevertheless, we note that there is minimal objective evidence that the strategy is working, and no recent independent evidence that it is being implemented successfully.

| Danish seine – north |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

It is unclear if the existing measures will work.

| (c) Shark-finning | ||

NA

CRITERIA: (iii) Information on the nature and amount of other species taken is adequate to determine the risk posed by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage other species.

| (a) Information Otter Trawl – Prawn |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Some quantitative information is available for retained non-target species through commercial logbooks, and for total catch composition (by number) through targeted, occasional research studies (e.g. Kennelly et al, 1998, Macbeth et al, 2008). There is no ongoing monitoring of non-retained species composition and volume. The available information is adequate to broadly identify the likely main other species in the fishery and estimate the impact of the fishery, but is not sufficient to assess the impact of the fishery with respect to status of main other species or to detect increased risk to them.

| Danish seine – north |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

There is very limited public information on catch composition in the Danish seine sector.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

2B: Endangered Threatened and/or Protected (ETP) Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species.

The UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The OTF Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) found all threatened and protected fish species to be at low or moderately low risk from the operation of the OTF (NSW DPI, 2004). The risk of the OTF impeding the conservation and recovery of threatened marine mammals and reptiles was assessed as low or moderately low, and that for threatened seabirds moderately low (NSW DPI, 2011).

No ETP interactions have been reported in commercial logbooks for the OTF since reporting was made mandatory in 2005. With the current gear used in the prawn otter trawl nets, an onboard observer based study observed very few ETP interactions (Macbeth et al. 2008). These included infrequent interactions with certain species of syngnathid; Hippocampus tristis, Solegnathus lettiensis and Solegnathus spinosissimus (20 individuals in total) and one Sandtiger Shark (Odontaspis ferox) caught over four trips. All of these individuals were returned to the water alive. Nevertheless, it is worth noting the study had relatively limited spatial and temporal coverage and relatively high levels of observer coverage are required to reliably estimate occurrence of infrequent events.

Gulper sharks have also been taken in the deeper areas of the OTF, although are unlikely to be incidentally taken in the fishery for the target species assessed here.

While qualitative information suggests that the impact of the fishery on ETP species is low, and that the fishery is therefore unlikely to be hindering recovery of ETP species, independent evidence (e.g. observer coverage) is very limited so it cannot be concluded with confidence that the fishery is highly unlikely to be hindering recovery of ETP species. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

- meet national and international requirements; and

- ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Under the FM Act the take of ETP species by commercial fishers is prohibited. The main measures in place which serve to limit interactions with ETP species include:

- limiting effort;

- gear design, including the use of bycatch reduction devices[1]; and

- a series of closures including a habitat closure including all reef habitat in the fishery, 18 area closures mainly situated around nearshore geographical features and overfished species (Dogfish, Mulloway and Gemfish) closures in habitat areas important for their life history or known aggregation sites.

The FMS also has a specific PI with a trigger for management action if there are any observations by commercial fishers or observers that are likely to threaten the survival of ETP species. Nevertheless, observer coverage has been low to non-existent and it is not clear whether other mechanisms have been used to monitor the ETP-related trigger points.

While the available evidence suggests interactions with ETP species are low and the existing measures are expected to ensure the fishery does not hinder recovery, the absence of ongoing validation of interactions means the information required to monitor performance against indicators remains relatively limited. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

[1] http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/352237/bycatch-closure.pdf

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The OTF EIS found that all threatened and protected fish species to be at low or moderately low risk from the operation of the OTF. The risk of the OTF impeding the conservation and recovery of threatened marine mammals and reptiles was assessed as low or moderately low, and that for threatened seabirds moderately low (NSW DPI, 2011).

Available onboard observer coverage indicates that interactions with ETP species are limited, and many captured ETP species (e.g. syngnathids) can be released alive (e.g. Macbeth, 2008). Accordingly, the measures in place are likely to work based on plausible argument. However, the absence of ongoing independent monitoring in the fishery to estimate levels of interaction and verify logbook reports of ETP interactions, limits the objective basis for confidence to conclude the measures are working.

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

- information for the development of the management strategy;

- information to assess the effectiveness of the management strategy; and

- information to determine the outcome status of ETP species.

| (a) Information |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The level of ETP interaction in the OTF is monitored through mandatory reporting in commercial logbooks for the OTF. However there has been very little independent monitoring of ETP interactions to verify the accuracy of logbooks reporting. The main study conducted (Macbeth et al, 2008) suggests some degree of non-reporting. Accordingly, while some quantitative information is available through compulsory logbook reports and isolated bycatch studies, confidence that these provide an up to date representation of current interactions with ETP species in the fishery is not strong. To that end, we have scored this SI medium risk.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

2C: Habitats

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to habitat structure and function, considered on the basis of the area(s) covered by the governance body(s) responsible for fisheries management

| (a) Habitat status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

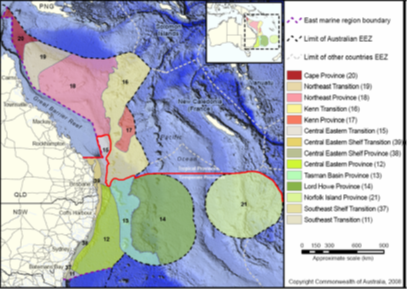

Australian seabed habitat has been classified using the Integrated Marine and Coastal Regionalisation of Australia Version 4.0 (IMCRA) (DEH, 2006) (Figure 2). The IMCRA is an ecosystem-based classification of Australia’s marine and coastal environments that was developed through the collaborative efforts of State, Territory and Commonwealth marine management and research agencies. Trawling for Eastern King Prawns is concentrated mainly off the north coast of NSW, with the majority of fishing occurring north of Newcastle in depths from 20 to 200m. Trawling targeted at Eastern School Whiting occurs year round on sandy bottoms in depths of 20 to 80m, mainly north of Sydney (DPI NSW, 2004). The majority of the Eastern King Prawn grounds occur within the Central Eastern Shelf Transition (CEST) bioregion categorised under the IMCRA. Trawling for Eastern King Prawn and Eastern School Whiting also occurs in the Central East Shelf Province (CESP).

Sediments in the CEST bioregion are relatively homogenous, dominated by sand with localised gravel deposits and negligible mud. Sand is the dominant sediment type associated with the geomorphic features found in this provincial bioregion including shelf, slope and shallow water terraces (DEWHA, 2009). Shallow water terraces in this provincial bioregion also contain a significant proportion of gravel. The absence of reefs was noted by Keene et al (2008) who characterised the Central Eastern Shelf Transition region as having <0.01% reef. In the CESP, sediment texture is dominated by sand with localised deposits of gravel in the north of the provincial bioregion. Observer studies have indicated that prawn trawling only occurs on sandy/muddy bottom (e.g. Macbeth et al. 2008).

Figure 3: Map of the East Marine Region depicting Provincial Bioregions (IMCRA v4.0) (from DEWHA, 2007)

The OTF EIS concluded that the otter-trawl gear used in the fishery had a high risk of causing enduring harm to the function and structure of biota associated with hard substratum, including biogenic habitat. Additionally, the OTF was rated as having a high risk of impacting biota associated with soft seabed habitat. The process used to identify risks to habitats and risk assessment outcomes were described in Astles et al (2009).

Since the EIS was written there have been a series of closures implemented in the fishery which protect all hard substratum as well as a substantial area of the fishery[1]. In addition, a number of new marine parks have been declared in NSW waters since 2005 (e.g. Cape Byron Marine Park, Port Stephens-Great Lakes Marine Park and the Batemans Marine Park) and large areas within these marine parks have been closed to trawling. Likewise, other management actions have been taken including prohibiting the use of bobbins on ground ropes of fish trawl nets north of Seal Rocks, and limiting the maximum size for bobbins on fish trawl nets south of Seal Rocks (NSW DPI, 2008). Work has also reportedly been done to map commercial trawling grounds out to 100 fathoms between the Queensland border and Coffs Harbour (NSW DPI, 2011), although no publicly available information on this has been found.

We have scored this SI medium risk on the basis that the evidence suggests the majority of available trawl ground is likely to be dominated by sandy habitat with little reef structure, trawlers are likely to actively avoid 3-dimensionally structured habitats and existing reef structures have received protection under law. Nevertheless, the publicly available evidence to assess the impact of the OTF on habitats is substantially weaker than comparative fisheries elsewhere in Australia (e.g. Queensland East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery; Commonwealth trawl fisheries) and the fishery would be better positioned against this SI with additional analysis to demonstrate either that risks were minor or that moderate or high risks have been dealt with to the extent that the fishery is not likely to reduce habitat structure and function of the point of serious or irreversible harm.

This is particularly the case for biota associated with soft seabed habitats for which levels of protection may not match those for reef areas. We note that considerable seabed mapping work (e.g. Davies et al. 2007, 2008a & b; Jordan et al, 2009) has been undertaken since the adoption of the FMS, and logbook reporting requirements have reportedly been refined to allow for a finer scale understanding of the spatial distribution of trawl effort. Further analyses of these data in support of achieving the FMS aim of estimating “a series of closures to trawling to protect a representative range of ocean habitats and their associated biota, in addition to those that are already protected within the boundaries of Marine Parks or permanent trawl closures” should be prepared for use in future assessments.

[1] http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries/info/closures/commercial/ot

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the habitats.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The main management measures in place which serve to limit habitat interactions in the OTF include limited entry, limits on vessel and gear size, as well as a series of closures including:

- A closure including all reef habitat in the fishery

- 18 area closures mainly situated around nearshore geographical features

- Overfished species (Dogfish, Mulloway and Gemfish) closures in habitat areas important for their life history or known aggregation sites

In addition, six multiple use marine parks covering around one third (approximately 345,000 hectares) of the NSW marine estate have been declared which include large areas closed to trawling[1].

The FMS “aims to establish a series of closures to trawling to protect a representative range of ocean habitats and their associated biota, in addition to those that are already protected within the boundaries of Marine Parks or permanent trawl closures. Included in this approach will be the closure of areas with ‘hard’ bottom habitats, which are at risk of being permanently modified by the effects of trawling. In the longer term, closures to trawling may be implemented to provide ‘refuge’ areas for species targeted by trawling as scientific information becomes available – these areas could include specific closures to protect habitats considered to be critical to the survival of any life-history stage of species taken by trawling.” The FMS also has a specific PI with a trigger for management action if there are any observations by commercial fishers or observers that are likely to threaten the survival of key habitats.

While information on the spatial footprint of fishing effort in the context of habitats within the fishery is currently limited, the available evidence suggest that fishing takes place over unconsolidated soft sediments (e.g. Macbeth et al, 2008), and there are measures in place which could be expected to ensure the fishery limits impact to areas of higher three dimensional structure (e.g. reef closures). In addition, marine parks have been established in inshore areas to protect representative samples of marine biodiversity. Accordingly, the measures in place which could be expected to ensure the fishery does not reduce the structure and function of habitats to the point of serious or irreversible harm and we have scored this SI medium risk. Nevertheless, the absence of quantitative analysis of the impacts of otter trawling and Danish seining on habitats types in the fishery mean that there is limited evidence upon which to support an effective strategy.

[1] http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/marine-protected-areas/marine-parks

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

There is a plausible argument that the management strategy is likely to work based on the fact that limited onboard observer coverage indicates that fishing occurs almost entirely over muddy/sandy bottom, and that there are large areas of sensitive habitat closed to the OTF. Prawns predominantly occur over soft seabed and prawn trawling cannot be successfully conducted over hard substratum due to gear loss. Nevertheless, there is very limited evidence to provide any objective level of confidence.

CRITERIA: (iii) Information is adequate to determine the risk posed to the habitat by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage impacts on the habitat.

| (a) Information quality |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The types and distribution of the main habitats have been well documented for the deeper shelf waters of the fishery (Bax & Williams 2001, Williams and Bax. 2001, Williams et al. 2009) and a major mapping program has provided information on the major habitat types and their location within NSW waters (Davies et al. 2007, 2008a & b, Jordan et al. 2009). The vulnerability of these habitats has been identified in the OTF EIS as well as the Commonwealth Trawl Fishery ERA. The main weakness appears to be the lack of fine scale spatial data on the distribution of trawl effort, particularly in relation to its potential overlap with vulnerable habitat types. We note that commercial logbooks have reportedly been redesigned to allow for finer scale spatial reporting which may help to address these weaknesses in future.

| (b) Information and monitoring adequacy |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Information is adequate to broadly understand the nature of the main impacts of gear use on the main habitats, including spatial overlap of habitat with fishing gear at broad scales. The physical impacts of prawn trawling has been well studied in other jurisdictions (e.g. ECOTF), however, the level of habitat interaction in the OTF at fine spatial scales does not appear to be well-understood and observer coverage has been limited in the fishery. Notwithstanding that, existing knowledge is probably sufficient to broadly understand the nature of the main impacts of gear use on the main habitats, and there is some information on the spatial overlap of habitats with fishing gear. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk. Nevertheless, the fishery would be considerably better positioned against this indicator with additional analysis of finer scale spatial effort patterns overlayed against finer scale habitat distribution maps now available for the NSW continental shelf.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

2D: Ecosystems

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to the key elements of ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Ecosystem Status |

LOW RISK |

|

Serious or irreversible harm in the ecosystem context should be interpreted in relation to the capacity of the ecosystem to deliver ecosystem services (MSC, 2014). Examples include trophic cascades, severely truncated size composition of the ecological community, gross changes in species diversity of the ecological community, or changes in genetic diversity of species caused by selective fishing.

Prawn trawling in the OTF is relatively unselective so the fishery can impact the ecosystem through removals of target, byproduct and bycatch species as well as modification of seafloor habitats. In the original EIS for the fishery five shark species, five teleost species and two crustacean species were rated as being at high or moderately risk of being overfished, and 95% of the non-commercial bycatch species (fish and invertebrates) had a high or moderately high level of risk (NSW DPI, 2004). Some of the recommendations from the EIS to mitigate the impact of these species have been implemented, such as introduction of BRDs, reduction of total effort, introduction of a network of spatial and temporal closures and the implementation of square mesh codends for high ‘bycatch areas’.

Atlantis ecological modelling undertaken on the ecosystem of the eastern Australian Continental Shelf using data from large trawl surveys completed in 1976 and 1996 indicated that, while the OTF is fully exploited with most target species being at less than half their original biomass, diversity indices are not likely to have been significantly impacted in the area of the fishery (Savina et al. 2013). The modelling predicted little change in detritus levels or in the lower trophic groups (e.g. plankton) in the 20 years to 1996, with the most significant changes in species groups that were under direct fishing pressure, where both the proportion of adults and total biomass typically decreased. Some non-harvested species, such as oceanic planktivores and mesopelagics, showed an increase in the proportion of adults, which was related to lower predation pressure from the heavily fished groups.

Notwithstanding information weaknesses around impacts on some ecosystem components (e.g. discards), the outcomes of the Atlantis modelling suggest the fishery is probably unlikely to disrupt the key elements underlying ecosystem structure and function to the point of serious or irreversible harm.

CRITERIA: (ii) There are measures in place to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The OTF FMS establishes the framework for the management of ecosystem impacts in the fishery, having as its first goal “management of the OTF in a manner that promotes the conservation of biological diversity in the marine environment” (NSW DPI, 2007). Underneath this goal, a number of objectives are set out with the aim of minimising ecosystem impacts including mitigating the impact of trawling in NSW waters on ecosystem integrity, non-retained species and habitats. For each objective a series of proposed management measures are specified including defining and mapping trawl grounds, implementing a series of closures to trawling to protect the range of ocean habitats and associated biodiversity, promoting research and collaborate with research institutions to improve our understanding of ecosystem functioning and how it is affected by trawling designing and implementing an industry funded scientific observer program to document the degree of interaction with non-retained and threatened species.

The FMS also establishes a framework of performance indicators and trigger points to monitor the implementation of the strategy.

While the FMS framework itself could be considered at least a partial strategy to restrain ecosystem impacts so as to achieve the outcome in criterion 2D(i), the extent to which the management measures have been implemented and monitored appears variable. While research on ecosystem impacts has been encouraged, limited progress appears to have been made on an observer program or habitat protection outside 3nm. Notwithstanding that, the fishery does have measures in place (e.g. gear restrictions, closed areas, BRDs) which take into account the potential impacts of the fishery on the ecosystem. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The outcomes of the Atlantis modelling provide at least some basis for confidence that the measures are working, although there is less evidence that all measures set out in the strategy have been implemented effectively (e.g. fishery observer program). Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

CRITERIA: (iii) There is adequate knowledge of the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem.

| (a) Information quality |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The key elements of the ecosystem where the OTF operates have been identified (e.g. NSW DPI, 2004, Fulton et al. 2011, Savina et al. 2013). However, given recent information on interactions with ecosystem components other than targeted species (e.g. discard volume and composition) is relatively limited, information is likely to be inadequate to detect increased risk to the ecosystem and trophic functioning.

| (b) Investigations of UoA impacts |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The main interactions of the OTF on these key ecosystem components can be inferred from existing information on species removals and broad knowledge of the food webs in this environment. While the impacts of removals by the OTF on the shelf ecosystem has been investigated using Atlantis modelling (Savina et al. 2013), data limitations around key ecosystem elements (e.g. discard composition and volume) mean that current impacts cannot be investigated in detail.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

COMPONENT 3: Management system

3A: Governance and Policy

CRITERIA: (i) The management system exists within an appropriate and effective legal and/or customary framework which ensures that it:

- Is capable of delivering sustainability in the UoA(s); and

- Observes the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom of people dependent on fishing for food or livelihood.

| (a) Compatibility of laws or standards with effective management |

LOW RISK |

|

The OTF is managed under the Fishery Management Act 1994 (Act) and regulations made under this Act. NSW DPI is the State Government agency responsible for the administration of the Act.

The Act seeks to provide for ecologically sustainable development for the fisheries of NSW through the achievement of its stated objectives, which are to conserve, develop and share the fishery resources of the State for the benefit of present and future generations. The Act is aimed at achieving sustainable fisheries in accordance with Components 1 and 2.

| (b) Respect for Rights |

LOW RISK |

|

In recognition of Aboriginal peoples’ cultural fishing needs and traditions, several significant Act amendments commenced in early 2010. They included:

- Extending the objectives of the Act to explicitly recognise the connection Aboriginal people have with the fisheries resource;

- The addition of a definition of Aboriginal Cultural Fishing to enable Aboriginal people to take fish or marine vegetation for cultural fishing purposes;

- The establishment of the Aboriginal Fishing Advisory Council (section 229) to ensure that Aboriginal people play a part in future management of the fisheries resource;

- Specific provisions under Section 37(c1) of the Act for issuing authorities for cultural events where fishing activities are not consistent with current regulation. This provision caters for larger cultural gatherings and ceremonies.

- Aboriginal persons being exempt from paying a recreational fishing fee under 34C of the Act.

In addition to the requirements of the Act, an Indigenous Fisheries Strategy and Implementation Plan (IFS) which was released in December 2002. The IFS put in place a process that will ensure discussion and negotiation to resolve problems and challenges in relation to Indigenous involvement in the fisheries of NSW.

CRITERIA: (ii) The management system has effective consultation processes that are open to interested and affected parties. The roles and responsibilities of organisations and individuals who are involved in the management process are clear and understood by all relevant parties.

| (a) Roles and Responsibilities |

LOW RISK |

|

The Organisations and individuals involved in the management process have been identified. Functions, roles and responsibilities are explicitly defined and well understood for key areas of responsibility and interaction. The Minister responsible for administering the Fishery Management Act 1994 is ultimately responsible for the management of NSW commercial fisheries. The NSW DPI undertake day to day management of the EGF and act as a primary advisor to the Minister. Other groups may also provide advice to the Minister or through the DPI, including the Ministerial Fisheries Advisory Council (MFAC), the Commercial Fishing NSW Advisory Council and the NSW Total Allowable Catch Setting and Review (TAC) Committee. For more information see:

http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries/commercial/consultation

| (b) Consultation Process |

LOW RISK |

|

Improved consultation arrangements were introduced in November 2012 following an Independent Review of NSW Commercial Fisheries Policy, Management and Administration. In addition to the Deputy Director General DPI Fisheries, who acts as the primary advisor to the Minister, key groups involved in the consultation process include:

- Ministerial Fisheries Advisory Council (MFAC) – established to provide cross-sectoral advice on strategic policy issues to the Minister for Primary Industries. It includes representatives from the commercial, recreational, indigenous, aquaculture and conservation sectors and has an independent Chair;

- Commercial Fishing NSW Advisory Council – the council is the key advisory body providing ongoing industry expert advice to Government on matters relevant to the sector. Membership covers each restricted and share managed fishery, as well as an aboriginal person who is a commercial fisher; and

- NSW Total Allowable Catch Setting and Review (TAC) Committee – The TAC Committee is a statutory body established under the provisions of the Fisheries Management Act 1994 (the Act). It is required to determine and keep under review total allowable catch (or fishing effort) levels, as required. It gives effect to the objects of the Act having regard to all relevant scientific, industry, community, social and economic factors. Membership of the TAC Committee includes an independent Chairperson, a natural resource economist, a fisheries scientist and a person with appropriate fisheries management qualifications.

Task based and time-limited ad hoc working groups may also be formed on an as needs basis to provide expert advice on specific issues. Working group members are appointed by the Deputy Director General, DPI Fisheries based on skill and expertise relevant to the tasks assigned to the working group. Current working groups include a Baitfish Working Group and a NSW Lobster Industry Working Group.

Where substantive changes are proposed to management arrangements, public consultations occurs through the release of a Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) which sets out the proposed changes, likely impacts and alternative options considered.

Accordingly, the management system has processes in place to regularly seek and accept information from interested parties.

For more information on the full process see: http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries/commercial/consultation

CRITERIA: (iii) The management policy has clear long-term objectives to guide decision making that are consistent with Components 1 and 2, and incorporates the precautionary approach.

| (a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|

The objectives of the Act include:

a) to conserve fish stocks and key fish habitats, and

b) to conserve threatened species, populations and ecological communities of fish and marine vegetation, and

c) to promote ecological sustainable development, including the conservation of biological diversity, and, consistently with those objectives:

d) to promote viable commercial fishing and aquaculture industries, and

e) to promote quality recreational fishing opportunities, and

f) to appropriately share fisheries resources between the users of those resources, and

g) to provide social and economic benefits for the wider community of New South Wales.

These objectives are consistent with Components 1 and 2.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

3B: Fishery Specific Management System

CRITERIA: (i) The fishery specific management system has clear, specific objectives designed to achieve the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2.

| (a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|

The OTF FMS has the following objectives for the fishery:

- Manage the OTF in a manner that promotes the conservation of biological diversity in the marine environment

- Maintain stocks of primary and key secondary species harvested by the OTF at sustainable levels

- Promote the conservation of threatened species, populations and ecological communities likely to be impacted by the operation of the OTF

- Appropriately share the resource and carry out fishing in a manner that minimises negative social impacts

- Promote a viable OTF, consistent with ecological sustainability

- Facilitate effective and efficient compliance, research and management of the OTF

- Improve knowledge about the OTF and the resources on which it relies

Additional fishery specific objectives and associated performance indicators and trigger points are set out in the Fisheries Management (Ocean Trawl Share Management Plan) Regulation 2006 (the ‘SMP’).

While these objectives are consistent with the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2, the main uncertainty is the extent to which the objectives as set out in the FMS actively guide management of the OTLF given the age of the document and the extent to which they have been superseded by other management initiatives (e.g. the BAP). We have scored this SI medium risk on the basis that objectives consistent with Components 1 and 2 are at least implicit within the management system, although we note that confidence in the scoring would be strengthened with additional evidence that the objectives in the FMS continue to be actively used.

CRITERIA: (ii) The fishery specific management system includes effective decision making processes that result in measures and strategies to achieve the objectives.

| (a) Decision making |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Under the NSW State Government’s fisheries decision-making process, the Fisheries Minister has ultimate responsibility for the management of the fishery and is empowered to make changes to the Fisheries Regulations and Management Plan. The Minister is advised by the NSW DPI and MFAC who, in turn, seek input from stakeholders and technical working groups.

The extent to which the management system could demonstrate that it has responded over time to all serious and other issues identified in relevant research, monitoring and evaluation in a timely, transparent and adaptive manner appears variable. For example, for Eastern School Whiting unconstrained State catches and weaknesses in data collection have long had the potential to undermine the effectiveness of the overall harvest strategy, although concerted management action appears to have been taken in recent years. A similar situation exists with the existence of substantial latent effort in the OTF, although action is now being taken through the BAP.

Nevertheless, there are examples in which the management system has responded to serious issues – for example, measures recover populations of dogfish and specific area closures implemented for the protection of critical habitats for grey nurse sharks. Given that there is some evidence that the management system responds to serious issues we have scored this SI medium risk.

| (b) Use of the Precautionary approach | MEDIUM RISK |

The use of the precautionary approach is required under the Act and is also addressed in Objective 1 in the FMS: To manage the OTF in a manner that promotes the conservation of biological diversity in the marine environment. Some examples of precautionary management in the fishery exist including prohibiting mid water trawls that target several overfished finfish species and the implementation of fishery closures on all reefs and in depths beyond 1100m. Nevertheless, there are management arrangements in place which appear to be less precautionary – for example, the existence of substantial excess harvesting capacity and limited understanding on catch composition and habitat impacts in some sectors. Accordingly, the fishery does not appear to meet the low risk scoring guidepost.

| (c) Accountability and Transparency |

LOW RISK |

|

Information on the fishery’s performance is available on the NSW DPI website, primarily through public reports of performance against the FMS trigger points (e.g. NSW DPI, 2016), stock status assessments (e.g. Stewart et al, 2015; NSW DPI, 2017b) and periodic reviews against the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries by the Commonwealth environment department (e.g. NSW DPI, 2013). Research reports relevant to the fishery are also available through the NSW DPI website (e.g. Macbeth et al, 2008) and websites of external funders (e.g. the Commonwealth Fisheries Research and Development Corporation). The findings of relevant research are discussed through the consultative structure. Where significant management changes are required, a RIS is released calling for public comment. The RIS provides an explanation of the background to the proposed changes and alternative options considered.

CRITERIA: (iii) Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms ensure the management measures in the fishery are enforced and complied with.

| (a) MCS Implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

The NSW fisheries compliance program is led by the NSW DPI Fisheries Compliance Unit (FCU), which is focused on optimising compliance with the Act, the Marine Estate Management Act 2014 and their associated regulations. The FCU is separated into seven geographic compliance zones, with a State-wide Operations and Investigations Group that undertakes major/complex investigations, and the Conservation and Aquaculture Group that provides specialist capabilities in aquatic habitat compliance management. NSW DPI Fisheries Compliance Plans are regularly reviewed for progress against the objectives of the Australian Fisheries National Compliance Strategy (AFNCS).

The MCS system in the OTLF primarily comprises commercial logbooks, at sea and land-based fisheries inspections of all sectors by the DPI Fisheries Officers and occasional observer coverage. Clear sanctions are set out in legislation enforceable through the courts with promotion of voluntary compliance through education. Additionally, there is a specific goal in the FMS to “facilitate effective and efficient compliance, research and management of the Offshore Trawl Fishery” with a trigger point to prompt a review if the percentage of inspections resulting in the detection of offences exceeds either of the following: 20% for minor offences and 10% for major offences. This trigger point is assessed at least biennially and compliance statistics are reported annually on the DPI website.

Significant prosecutions and rates of compliance are publicly reported on the DPI website. The compliance system appears to have an ability to enforce relevant management measures and rules.

| (b) Sanctions and Compliance |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Sanctions to deal with non-compliance are set out in the Act and the NSW Fisheries Compliance Enforcement Policy and Procedure document (NSW DPI, 2011). Some evidence exists that fishers comply with the management system, including providing information of importance to the effective management of the fishery (e.g. catch and effort through logbooks). DPI (2017a) report that the annual rates of compliance in the OTF during the period 2012-13 to 2015-16 were:

- 2012/13 – 83.93%

- 2013/14 – 82.91%

- 2014/15 – 81.67%

- 2015/16 – 76.74%

The rate of compliance is calculated using information collected during fisher and fishing gear inspections and recorded in program activity reports that are completed by NSW DPI Fisheries Officers. The rates of compliance reported above are lower than might be expected in a high compliance fishery, and there is some evidence that interactions with ETP species may be under-reported (e.g. Macbeth et al, 2008). Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

CRITERIA: (iv) There is a system for monitoring and evaluating the performance of the fishery specific management system against its objectives.

There is effective and timely review of the fishery specific management system.

| (a) Evaluation coverage |

LOW RISK |

|

There are mechanisms in place to monitor performance of the management system against various trigger points in the FMS and SMP, as well as through annual stock status assessments. The FMS and SMP set out operational objectives and performance indicators across the key elements of the management systems: target species, byproduct species, bycatch species, ecosystems and social indicators. In addition, NSW DPI Fisheries Compliance Plans are regularly reviewed for progress against the objectives of the Australian Fisheries National Compliance Strategy (AFNCS).

| (b) Internal and/or external review |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The fishery is subject to occasional external review by the Commonwealth Department of the Environment against the requirements of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Generally, assessments have occurred every three years, with the current accreditation scheduled to expire in 2018. The extent to which the fishery management system has been subject to regular internal review is somewhat unclear. Performance against the FMS was to be subject to biennial review under the MAC. However, the plan for reviews under the new consultative structure is not available publicly. Notwithstanding that, it is clear that at least occasional reviews of performance against the FMS have occurred (e.g. DPI, 2016). Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM

Acknowledgements

This seafood risk assessment procedure was originally developed for Coles Supermarkets Australia by MRAG Asia Pacific. FRDC is grateful for Coles’ permission to use its Responsibly Sourced Seafood Framework.

It uses elements from the GSSI benchmarked MSC Fishery Standard version 2.0, but is neither a duplicate of it nor a substitute for it. The methodology used to apply the framework differs substantially from an MSC Certification. Consequently, any claim about the rating of the fishery based on this assessment should not make any reference to the MSC.