Grey Mackerel – Gulf of Carpentaria Inshore Fin Fish Fishery

Assessment Summary

Grey Mackerel

Unit of Assessment

Product Name: Grey Mackerel

Species: Scomberomorus semifasciatus

Stock: Grey Mackerel – Gulf of Carpentaria

Gear type: Gillnet

Fishery: Gulf of Carpentaria Inshore Fin Fish Fishery

Year of Assessment: 2017

Fishery Overview

The Gulf of Carpentaria Inshore Fin Fish Fishery (GOCIFFF) extends from Slade Point near the tip of Cape York Peninsula westward to the Queensland–Northern Territory border and operates in all tidal waterways out to the boundary of the Australian Fishing Zone (AFZ).

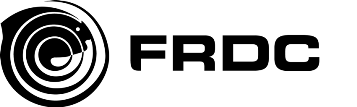

The GOCIFFF is a multi-species fishery and includes commercial, recreational (including charter) and indigenous fishing (DAFF, 2014). The commercial fishery constitutes mesh net fishing under the N3 (within 7nm of the Queensland coastline), N12 (beyond 7 nm from shore and within the AFZ), N13 (beyond 25 nm from shore and within the AFZ) fishery symbols (Figure 1), as well as commercial netting for bait under a N11 symbol within 25 nm of the shoreline (DAFF, 2014). As of 3rd April, 2017, 85 N3 symbols existed, with three N12 symbols and a single N13 symbol. The commercial sector tends to target Barramundi, King and Blue Threadfins, Blacktip Sharks, Grey Mackerel and Baitfish while the recreational sector targets these species (with the exception of Blacktip Sharks) as well as Mangrove Jack, Goldspotted Rockcod and Javelin Fish (DAFF, 2014).

Figure 1: Area of the (a) N3, (b) N12 and (c) N13 fishery symbols in the Gulf of Carpentaria fin fish fishery. (Source: Qld Department of Agriculture and Fisheries).

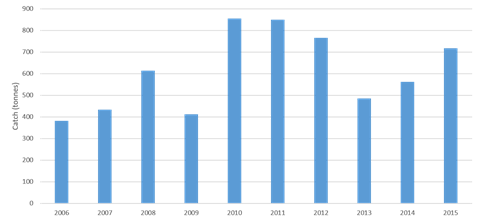

Total commercial harvest in the Gulf net fisheries in 2016 of 1,759 tonnes (t) was up slightly from the 1,560 t in 2015[1]. Grey Mackerel accounted for around 37% of the catch in 2016, with Blacktip Sharks accounting for around 12%. The other main species taken in the fishery are Barramundi (27%) and King Threadfin (10%).

Queensland and the Northern Territory share management of the Gulf of Carpentaria biological stock of Grey Mackerel through the Queensland Fisheries Joint Authority (QFJA). Queensland takes the majority of the commercial harvest (average 80–95 per cent) (Helmke et al, 2016). In Queensland waters, jurisdictional responsibility for the inshore gillnet fishery (N3) lies solely with Queensland, while the offshore fisheries (N12, N13) are managed by Queensland on behalf of the QFJA.

[1] https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/fisheries/monitoring-our-fisheries/data-reports/sustainability-reporting/queensland-fisheries-summary/gulf-of-carpentaria-inshore-fin-fish-fishery#30

Figure 2 Trends in total catch

Risk Scores

|

Performance Indicator |

Risk Score |

|

LOW RISK |

|

|

1A: Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

LOW RISK |

|

C2 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF FISHING |

HIGH RISK |

|

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

|

2B: ETP Species |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

2C: Habitats |

LOW RISK |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

C3 MANAGEMENT |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW RISK |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

MEDIUM RISK |

Summary of main issues

- There are no well-defined HCRs in place for Grey Mackerel.

- There is limited recent information on total catch composition (retained catch + discards).

- There is uncertainty around reporting of ETP species interactions, and there is currently no mechanism to independently validate interactions.

Outlook

| Component | Outlook | Comments |

| Target fish stocks | Improving ↑ | In the GOCIFFF harvest strategies with well-defined harvest control rules will be developed by 2018 as part of the Queensland Government’s Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027. Improved arrangements for monitoring and validation of fisher logbooks will also be introduced. Management arrangements in the NT ONLF are also currently under review with a new management plan scheduled to be released shortly. This is expected to include well-defined harvest control rules consistent with the NT Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy. |

| Environmental impact of fishing | Improving ↑ | Improved arrangements to monitor and assess impacts on non-target species are proposed to be introduced as part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027. These include a new ecological risk assessment (ERA) for the Gulf Fin Fish Fishery by 2020, and improved arrangements to validate ETP species interactions. |

| Management system | Improving ↑ | A range of improvements to the management system are proposed as part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027, including strengthened stakeholder engagement, measures to strengthen compliance and measures to evaluate the performance of the management system (e.g. through monitoring against harvest strategies). |

COMPONENT 1: Target fish stocks

1A: Stock Status

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing.

| (a) Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

At least five Grey Mackerel biological stocks exist across northern Australia, including a Western Australia stock, a north-west Northern Territory (Timor/Arafura) stock, a Gulf of Carpentaria stock, a north-east Queensland stock and a south east Queensland stock (Welch et al. 2009). The GOCIFFF harvests the Gulf of Carpentaria (GoC) stock.

The GoC Grey Mackerel stock has been assessed using a Stock Reduction Analysis (SRA) model (Grubert et al. 2013). The model for the GoC stock, which includes data from both Northern Territory Offshore Net and Line Fishery (ONLF) and the GOCIFFF suggests that despite recent increasing catches, the current biomass is 74% of unfished levels (Grubert et al. 2013). This evidence suggests that it is highly likely the stock is above PRI and likely to be above levels capable of producing MSY.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

1B: Harvest Strategy

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place.

| (a) Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

|

Harvests of the GoC Grey Mackerel stock are shared between the GOCIFFF and the Northern Territory Offshore Net and Line Fishery (ONLF). The GOCIFF took the majority (88 per cent) of the commercial harvest in 2015 and has averaged 80–90 per cent of the harvest in recent years (Helmke et al, 2016).

In the GOCIFFF harvest limitation for the target species is achieved primarily through limiting licences in the commercial sector, restricting gear, a minimum legal size limit of 60 cm, a recreational personal possession limit of five fish and spatial closures.

Queensland introduced changes to the net fishery at the beginning of the 2012 season to reduce pressure on Grey Mackerel. The measures decreased the total length of available net for the Queensland component of the stock by two-thirds, from 27 km to 9 km, in the offshore component of the fishery. Changes to the Queensland inshore fishery (within 7 nautical mile of the coast) also reduced the capacity for boats to target Grey Mackerel. A Performance Measurement System (PMS) was previously in place for the fishery (DAFF, 2009) that aimed to monitor trends against reference points (e.g. catch and/or catch rates being 30% above or below the annual average of the previous five years) although assessments against this framework appear to have been largely discontinued. Stock status is assessed regularly in recent years using a weight of evidence approach, and takes into account relevant quantitative assessments undertaken by other jurisdictions (e.g. Grubert et al, 2013).

The Queensland Government has recently announced the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027 which commits, amongst other things, to improved monitoring and research and the adoption of harvest strategies for all major fisheries by the end of 2020, with a priority to develop trawl, crab and inshore fisheries strategies by the end of 2018 (DAF, 2017a). Harvest strategies will include well-defined harvest control rules and aim to maintain stocks at levels above MSY.

The main management measures in place for the gillnet sector of ONLF include:

- Limited entry – 17 licensees in 2017;

- Spatial restrictions – pelagic gillnetting is permitted seaward of two nautical miles offshore only;

- Gear restrictions – maximum net length (2,000 metres) per licence with a maximum of 100 meshes drop, prohibition of bottom setting of nets, net mesh size restrictions (between 160 and 185 millimetres); and

- Effort limits – total allowable effort limits allocated through individually transferable effort units, including 1,599 net fishing days per annum.

The fishery is monitored through compulsory catch and effort logbooks requiring fishers to submit monthly summary returns. Catch and effort is validated through independent observer coverage (NTG, 2017). Periodic stock assessments are also undertaken (e.g. Grubert et al, 2013). DPIF (2016) report that the Department is currently undertaking a review of the ONLF which will likely result in the introduction of a TACC/ITQ based management system, underpinned by a formal harvest strategy.

In the GOCIFFF, there is some evidence that the harvest strategy is responsive to the state of the stock given the measures to reduce perceived pressure on Grey Mackerel introduced in 2012. Status is assessed regularly, although no formal harvest control rules are in place. In the ONLF, there has been no reason to reduce exploitation as a result of stock declines, although stock status is assessed at least biennially based on relevant indicators and tools existing to reduce exploitation if necessary. Recent estimates suggest the stock is being harvested at levels well below MSY, with SRA analysis concluding that the harvest rate is at 26 per cent of that required to achieve MSY (Grubert et al, 2013). Accordingly, we have scored this SI low risk. Nevertheless, the fishery would be better placed against this SI with well-defined harvest control rules in place which served to reduce exploitation as PRI is approached.

| (b) Shark-finning |

NA |

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place.

| (a) HCR Design and application | MEDIUM RISK | |

In the GOCIFFF, monitoring was previously undertaken against trigger points in a specific PMS for the fishery, although assessments against framework have been largely discontinued. In the ONLF, while harvest strategy performance is assessed against a set of trigger points they currently do not link clearly to the state of stock nor set out pre-agreed response to reduce exploitation if PRI is approached. Accordingly, “well-defined” HCRs are not in place in either jurisdiction.

Nevertheless, assessments of stock status are undertaken annually in the Northern Territory (e.g. NTG, 2017), as well as by both jurisdictions biennially through the Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks process (e.g. Helmke et al, 2016), and tools are in place (e.g. adjustments to net length, effort limits) that allow exploitation to be reduced if the stock was identified as approaching the PRI. Moreover, the 2012 changes to reduce the potential for exploitation of Grey Mackerel in Queensland in response to concerns about stock status provide some evidence that the management system will act in response to concerning trends. To that end, generally understood harvest control rules and tools could be said to be available which are expected reduce exploitation as PRI is approached.

We note that a harvest strategy with well-defined harvest control rules aiming to maintain stocks at levels above MSY will be developed for Queensland’s inshore fisheries by the end of 2018 as part of the recently announced the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027 (DAF, 2017a). We also note that management arrangements in the ONLF are currently under review and future arrangements are expected to well-defined HCRs consistent with the NT Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy (DPIR, 2016).

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

1C: Information and Assessment

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy.

| (a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|

The biology of Grey Mackerel is well known including information on stock structure, reproductive biology, age, growth and longevity (e.g. Cameron and Begg, 2002; Welsh et al, 2009; Broderick et al, 2011). Good information on commercial sector fleet composition is available through licensing details for both the ONLF and GOCIFFF, as well as through compulsory catch and effort logbooks. Independent information is also available through observer coverage in the ONLF. Periodic recreational fishing surveys provide information on the fleet composition and catch and effort by this sector (e.g. Webley et al, 2015; West et al, 2012). Recreational catch of Grey Mackerel in the NT was around 10t in 2013. Estimates of Grey Mackerel catch by Queensland fishers in the 2013-14 survey were uncertain, but are thought to be limited. While the Indigenous harvest is unknown it is likely to be very small given the offshore distribution of the target species (NTG, 2017). Notwithstanding the absence of well-defined harvest control rules, the available information is sufficient to support the harvest strategy.

| (b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

LOW RISK |

|

Grey Mackerel catches are monitored annually through the stock status reporting process and there is good information on catch and effort from the GOCIFFF and ONLF, which account for the majority of UoA removals. Additionally, regular information on the age and size structure of the target species is gathered during observer trips in the ONLF. Information on recreational catch is provided through periodic surveys (e.g. West et al, 2012; Webley et al, 2015), although catch estimates from the 2013/14 Queensland survey are considered uncertain. Periodic assessments of stock status have been undertaken which provide current estimates of biomass compared to B0 (e.g. Grubert et al, 2013). Although there are no well-defined HCRs in either jurisdiction, stock abundance and UoA removals are monitored with sufficient regularity to support an effective HCR (largely through assessments and monitoring undertaken in the Northern Territory jurisdiction), and there is sufficient information on other fishery removals from the stock.

CRITERIA: (ii) There is an adequate assessment of the stock status.

| (a) Stock assessment |

LOW RISK |

|

The GoC Grey Mackerel stock has been assessed using Stock Reduction Analysis models (Grubert et al. 2013). The stock is assessed using data from the NT ONLF and GOCIFFF. The output from the model estimates current biomass as a proportion of B0 and the assessment is considered appropriate for the stock and would support a biologically-based harvest control rule. The assessment also takes into account the major features of each fishery and the biology of both species.

| (b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

LOW RISK |

|

The stock assessment takes into account the major sources of uncertainty, and has been peer reviewed externally (Grubert et al, 2013). The annual stock status reports produced by the NT are reviewed internally (e.g. NTG, 2017).

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

2A: Other Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI.

| (a) Main other species stock status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The intent of this scoring issue is to examine the impact of the fishery on ‘main’ other species taken while harvesting the target species. ‘Main’ is defined as any species which comprises >5% of the total catch (retained species + discards) by weight in the UoA, or >2% if it is a ‘less resilient’ species. Blacktip sharks are assessed under Component 1 in the full assessment report. The aim is to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired and ensure that, for species below PRI, there are effective measures in place to ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery and rebuilding.

The majority of Grey Mackerel and Blacktip sharks are targeted in the ‘offshore’ component of the GOCIFFF, namely by N12 and N13 symbol holders (previously ‘N9’ symbol) and also by N3 symbol holders fishing in deeper waters (i.e. >2m at low water) (e.g. DPIF, 2006). While limited independent information is available on the total catch (retained species + discards) in recent years, a compulsory, industry-funded observer program operated in the N9 fishery from 2000 to 2006 (Stapley and Rose, 2009). The program observed a total of 368 net sets, accounting for an average of 7% of fishing effort. A total of 83,092 fish were reported captured, of which 82% were used (processed /marketed), 15.5% were returned to the ocean dead and 2.5% returned alive. Roelefs (2003) reports that while the observer program operated only between 7nm and 25nm, there is no reason to believe catch composition would be substantially different in waters outside of 25nm. He also notes that because of similarity of habitat, bycatch levels for ‘offshore’ shark and mackerel boats in the N3 fishery would be similar to those for the N9 fishery. To that extent, the information provided by the N9 observer program between 2000 and 2006 represents the best available data on likely catch composition of current vessels.

Across the seven years observed, a total of 112 species from 44 families were captured during the observer trips (Stapley and Rose, 2009). Only the number of reported captures were recorded, rather than weights. The top 10 species reported by number are set out in Table 2. Apart from the species assessed here as targets (noting that Spot-tail shark was reported separately by observers), only Longtail Tuna would qualify as a ‘main’ other species, based on numbers reported. Scalloped Hammerhead Shark would likely be considered a ‘less resilient’ species based on its life history characteristics, though is assessed as an ETP species under 2B below. It is possible that Milk Shark may account for >2% of the total catch by weight, although given the average size of Milk Sharks observed in N9 nets was smaller than most other captured species the likelihood is low. The average size of captured Winghead Sharks was larger than Milk Sharks but there is insufficient information available to determine whether the species will have accounted for >2% of the catch by weight overall. On that basis, we have assessed Longtail Tuna as the ‘main’ retained species.

Table 2: Top 10 species reported by number in the N9 observer program, 2000-2006 (Stapley and Rose, 2009)

| Species | % of catch by number |

| Grey Mackerel | 44.08 |

| Blacktip Shark (C. tilstoni and C. limbatus) | 19.60 |

| Longtail Tuna | 5.27 |

| Spot-tail Shark | 4.76 |

| Black Pomfret | 4.23 |

| Spanish Mackerel | 2.73 |

| Scalloped Hammerhead Shark | 2.43 |

| Blue Threadfin | 1.83 |

| Milk Shark | 1.73 |

| Winghead Shark | 1.21 |

Longtail Tuna

Limited information is available on the stock structure of Longtail Tuna (Thunnus tonggol) throughout its worldwide distribution (Griffiths et al, 2010). In the absence of clear stock delineation, Griffiths (2010) assumed a single stock of longtail tuna exists from the central Arafura Sea and eastward along the eastern coast of Australia. He noted that differences in the size composition at capture across different regions in Australia provide a strong argument that longtail exist as a single stock in Australian waters and that northern Australia is a nursery habitat from which fish radiate eastward and southward.

The 2006 ERA workshop estimated that 5-10t of tuna were captured in the N9 fishery annually and concluded that the impact on the stock was likely to be negligible (Zeller and Snape, 2006).

More recently, Griffiths (2010) used yield-per-recruit analyses to estimate fishing mortality for the main commercial and recreational fisheries for Longtail Tuna during the 2004 to 2006 period. He concluded that F did not exceed FMSY across a range of plausible values of natural mortality (M). Moreover, F approached a precautionary F0.1 reference point only where the lowest plausible estimate of natural mortality was used. Overall, he concluded that Longtail Tuna are ‘probably being fished at biologically sustainable levels, with some scope for a limited increase in fishing mortality’.

Since the data collection for the study was undertaken, Longtail Tuna have been declared a ‘recreational-only’ species by the Commonwealth, with Queensland commercial fishers limited to 10 fish in possession. For this reason, Stapley and Rose (2009) report that fishers tend to discard the species and targeting will not have increased. Nevertheless, given the species is taken incidentally, actual catch rates will be influenced by effort levels targeting the main commercial species in the fishery. While effort levels specific to the ‘offshore’ component of the GOCIFFF are not reported, overall levels of nominal effort in the fishery have reduced since 2004-2006[1]. Moreover, management interventions introduced in 2012 are reported to have reduced effort directed at Grey Mackerel (DAFF, 2014). To that extent, there is a plausible argument that GOCIFFF-related mortality on Longtail Tuna is unlikely to have risen substantially since the Griffiths (2010) study.

Given the above, we have scored this SI medium risk on the basis that it is at least likely that main other species are above the PRI.

[1] https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/fisheries/monitoring-our-fisheries/data-reports/sustainability-reporting/queensland-fisheries-summary/gulf-of-carpentaria-inshore-fin-fish-fishery

CRITERIA: (ii)There is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

The main management measures in place which serve to monitor and limit fishing mortality on non-target species are similar to those for the target species and include:

- Limited entry;

- Gear restrictions (e.g. number, length, drop and mesh size of nets)

- Seasonal closure covering the Barramundi spawning period; and

- Monitoring through compulsory catch and effort logbooks.

An observer program operated in the fishery from 2000 to 2006, although has since been discontinued (Stapley and Rose, 2009).

For Longtail Tuna specifically, the species has been declared ‘recreational-only’ by the Commonwealth Government and Queensland fishers are subject to a possession limit of 10 fish. While the measure prevents targeting, the extent to which actual fishing mortality has been influenced is unknown since (a) the species is taken incidentally, (b) it is typically discarded (Stapley and Rose, 2009) and (c) there has been an absence of independent monitoring since 2006. DEEDI (2010a) suggest that commercial net fishers have found the 10 fish possession limit restrictive “given the relative abundance of these species in the Gulf of Carpentaria and the resulting potential for incidental capture”.

While there is a plausible argument that the possession limit, combined with overall restrictions on effort targeted at Grey Mackerel and Blacktip Sharks, could be expected to maintain the Longtail Tuna stock at levels likely to be above PRI, or at least not hinder recovery if necessary, the extent to which this occurs in practice is difficult to assess in the absence of information on recent catches.

Accordingly, we have scored this SI precautionary high risk. We note the fishery would likely be substantially better positioned against this SI with better monitoring of catch composition.

| (b) Management strategy evaluation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The most recent assessment of Longtail Tuna concluded that the stock was probably being fished at biologically sustainable levels, with some limited scope for an increase in fishing mortality (Griffiths, 2010). Since the study was undertaken, limits on targeting through the 10 fish possession limit and measures to contain nominal effort on the main commercial species, mean that fishing mortality associated with the offshore component of the GOCIFFF is unlikely to have increased substantially. To that end, there is a plausible argument that the measures in place could be considered likely to work. Nevertheless, without more recent information on catches and use of that information to determine appropriate harvest levels , there is limited scope for an objective basis for confidence.

| (c) Shark-finning | ||

NA

CRITERIA: (iii) Information on the nature and amount of other species taken is adequate to determine the risk posed by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage other species.

| (a) Information |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

The main sources of information on non-target species in the offshore component of the GOCIFFF come from compulsory fisher catch and effort logbooks, the fishery observer program which ran from 2000 to 2006 (Stapley and Rose, 2009) and other ad hoc research projects (e.g. Salini et al, 2007). Griffiths (2010) undertook a yield per recruit based stock assessment of Longtail Tuna, while Griffiths et al (2010) examined age and growth in the species.

While there is historical qualitative and some quantitative information to assess the likely impact of the GOCIFFF on main other species, very limited public information exists on total commercial catch composition (retained species + discards) since 2006. No ongoing program exists to independently monitor commercial catch composition or verify commercial logbooks. To that end, limited information exists to either identify species which are currently likely to qualify as ‘main’ other, and to assess impacts with respect to status. Accordingly, we have scored this SI precautionary high risk.

We note that measures to independently validate commercial logbook information will be strengthened as part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027 (DAF, 2017a), and an update to the GOCIFFF ERA is scheduled to be produced in 2017-18. Both of these initiatives should better position the UoA against this SI.

PI SCORE – PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK

2B: Endangered Threatened and/or Protected (ETP) Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species.

The UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

Data on interactions with ETP species in the GOCIFFF is collected each year as part of the Species of Conservation Interest (SOCI) reporting, although reporting of interactions is not separated into inshore and offshore components of the fishery. DAF (2017b) reports that the fishery as a whole may interact with dugongs, dolphins (particularly inshore dolphin species), marine turtles, Green, Dwarf and Largetooth (freshwater) Sawfish, Speartooth Sharks, crocodiles, whales and seabirds. Annual summaries of reported interactions are provided to the Commonwealth environment department (DAF, 2017b), although the most recent year for which publicly available information exists is 2012. In that year, reported ETP species interactions for the GOCIFFF as a whole included; five saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus, with only one being released alive), two freshwater sawfish (Pristis microdon, both released alive) and one unidentified saltwater turtle (released alive) (DAFF, 2014).

The number and fate of ETP interactions reported in logbooks have historically been confirmed by onboard observer trips (e.g. Stapley and Rose, 2009), although there has been no observer coverage in the offshore component of the fishery since 2006. In the period 2000-2006, Stapley and Rose (2009) reported that nine ETP species were caught incidentally in the N9 fishery, all of which were rarely encountered except the Narrow Sawfish (which is listed under the EPBC Act as a migratory species, but not in one of the threatened species categories). Some species were reported to have high survival rates upon return to the water – for example, three of four sea turtles captured and 12 of 15 Giant Manta Rays (Manta birostris) were released alive – while others had poor survival – 10 dolphins were observed captured over the seven year period (including eight Bottlenose Dolphins [Tursiops spp.], one Indo-Pacific Humpbacked Dolphin [Sousa chinensis] and one Australian Snubfin Dolphin [Oracella heinsohni]), all of which were returned to the water dead.

An ERA conducted in 2006 on the fishery rated the offshore component of the fishery as low or negligible risk to all ETP species, except bottlenose dolphins which were rated moderate risk (Zeller and Snape, 2006).

More recently, DoE (2015) report that Largetooth, Green and Dwarf Sawfish are recorded as part of the incidental catch in the gillnet fisheries in the Gulf of Carpentaria and that in the 2011 fishing season a total of 25 interactions were reported through the SOCI logbooks. This included 12 Largetooth Sawfish and three Dwarf Sawfish of which all but one Largetooth Sawfish were released alive. However, Peverell, 2005 (in DoE, 2015) reports that interactions with sawfish occur more rarely in the offshore components of the fishery, and only Narrow Sawfish were reported captured in the 2000-2006 observer study in the N9 fishery (Stapley and Rose, 2009).

Comparisons between observer reports and fisher logbooks indicate that under-reporting of ETP species interactions may be occurring in SOCI logbooks. For example, in 2009 (the last time there was observer coverage in the N3 fishery), a total of 21 interactions were reported through the SOCI logbooks for the GOCIFFF. This included 12 Largetooth Sawfish and two Dwarf Sawfish (DoE, 2015). However, the observer program, which observed <1% of effort in the fishery, reported a total of 26 interactions with the five listed species of sawfish and river sharks including one dwarf sawfish, 20 Largetooth Sawfish, one Green Sawfish and four Speartooth Sharks (DoE, 2015). Of those, the sawfish were mostly reported as being returned alive but three of the four Speartooth Sharks died during capture. DoE (2015) concluded that “there is an obvious discrepancy between the SOCI logbook data and the observer data, which suggests a high degree of underreporting is taking place in this fishery”.

Two species that weren’t considered in the ERA as ETP species given their recent listing are the Scalloped Hammerhead and Great Hammerhead (included on CITES Appendix II in September 2014 and recognised under the Commonwealth EPBC Act). On the basis of the information available on the population of this species within Australian waters and within the Oceania region, the CITES Scientific Authority of Australia has found that current levels of catch are unlikely to be detrimental to these species (DoE, 2014). The current catch level accepted as non-detrimental to Scalloped Hammerhead and Great Hammerhead stocks has been capped at 200 t per year and 100 t per year respectively for Australian fisheries. This catch level was considered unlikely to harm stocks of either species given strict management on the take of sharks across northern Australia and some evidence of other more heavily exploited species of sharks (Blacktip Sharks) showing positive signs of recovery since being heavily fished by the Taiwanese gillnet fishery in the 1970’s and 1980’s (Bradshaw et al., 2013). DoE (2014) notes that this research may also suggest a recovery of Scalloped Hammerheads and Great Hammerheads in the same area.

In the absence of recent observer data to verify the level of interactions with ETP species, and given the possibility of under-reporting in SOCI logbooks, a robust assessment of the impact of the fishery on these species is difficult. The most recent ERA (2006) for the fishery rated the risk of the offshore component of the fishery to ETP species as moderate to negligible, however the assessment is now dated and the quantitative information on which to examine risk may be weaker in the absence of independent verification of SOCI logbooks. Given the overall operation of the fishery is unlikely to be substantially different from that observed between 2000 and 2006, we have scored this SI precautionary high risk. Nevertheless, we note the fishery would be substantially better positioned against this SI with an independent means of verifying ETP species interactions.

We note that a number of measures are currently underway or planned which may better position the fishery against this SI in future. These include an update to the ERA for the GOCIFFF by 2020, and the planned introduction of mechanisms to independently validate data on interactions with protected species as part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027 (DAF, 2017a).

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

- meet national and international requirements; and

- ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

The measures in place to manage impacts on ETP species largely comprise limiting entry into the fishery, restricting gear, spatial restrictions, a three month seasonal closure and compulsory reporting of ETP species interactions in SOCI logbooks. A prohibition on bottom setting of nets exists in offshore waters (>2m at low tide) and fishers are also required to be in ‘attendance’ at nets while fishing to minimise harm to ETP species. A Code of Conduct requiring fishers to minimise interactions with ETP species has also been developed by the Gulf of Carpentaria Commercial Fishermen’s Association[1].

A specific performance indicator existed in the PMS for the fishery that required a management response if ETP interactions in any fishing year exceed historical maximum values. Likewise, Scalloped Hammerheads also had an additional performance indicator of CPUE for this species being 30% above or below the annual average of the previous three years and any increase in the number of licences that have more than 20% of their total catch comprising of Scalloped Hammerhead. However, the extent to which assessments against this framework are still undertaken is not clear.

In January 2018, new management measures for hammerhead sharks came into force including a total allowable commercial catch of 50t in Queensland-managed Gulf of Carpentaria fisheries and more stringent reporting arrangements[2].

While collectively the measures may ensure the fishery does not hinder the recovery of ETP species, the main weakness is the uncertainty in SOCI logbook reporting. In the absence of independent mechanisms to validate ETP species interactions, SOCI logbooks are the only available indicator to track interactions in the fishery. Given the uncertainty in reporting of at least some species, it is not clear if the current measures in place could be expected to ensure the fishery does not hinder recovery.

[1] https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/7cc0ad_45b0466c3abe4e329177e8b7b4100c2a.pdf

[2] https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/about-us/news-and-updates/fisheries/news/new-rules-commence-for-hammerhead-sharks

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Limitations on effort, together with the three month seasonal closure, the prohibition on bottom setting, a requirement to attend nets and release any captured animals unharmed and to report interactions in SOCI logbooks could be considered likely to work based on plausible argument. Nevertheless, the absence of any ongoing independent monitoring of interactions and uncertainties associated with reporting in SOCI logbooks means there is limited objective basis for confidence that the measures/strategy will work.

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

- information for the development of the management strategy;

- information to assess the effectiveness of the management strategy; and

- information to determine the outcome status of ETP species.

| (a) Information |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

The biology of some ETP species encountered has been relatively well studied (e.g. Peverell 2008), although there is limited information available on the population size and structure of Bottlenose Dolphins[1] which were rated moderate risk in the offshore sector by the 2006 ERA. The fishery has been subject to some level of independent observer coverage in the past (e.g. Stapley and Rose, 2009) which provided quantitative information in interactions. An ERA was conducted which used both quantitative and qualitative information to assess likely risk to ETP species (Zeller and Snape, 2006). Nevertheless, concerns about the accuracy of SOCI logbook reporting have been expressed (e.g. DoE, 2015) and the absence of any ongoing independent monitoring to verify SOCI reporting weakens confidence that existing information is adequate to estimate the UoA related mortality on ETP species and is adequate to support measures to manage the impacts on ETP species. Accordingly, we have scored this indicator precautionary high risk.

[1] http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=68417

PI SCORE – PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK

2C: Habitats

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to habitat structure and function, considered on the basis of the area(s) covered by the governance body(s) responsible for fisheries management

| (a) Habitat status |

LOW RISK |

|

Monofilament gillnet is generally considered to be “passive” and the risk to benthic habitats is minimal. In the offshore fishery, nets are surface set and anchored to a mud bottom. Nets only interact with seabed biota in depths less than around 8 metres (the maximum drop of nets used in the fishery). Offshore waters reach about 50 m in depth. Habitat interactions by the GOCIFF gear were considered negligible in the ERA (Zeller and Snape, 2006).

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the habitats.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

The main ‘strategy’ in place to limit impacts on habitats is the use of passively fished gillnet gear, which has previously been assessed as having a negligible impact on habitats (Zeller and Snape, 2006). Together with other measures such as limiting entry into the fishery, restricting gear, prohibiting bottom setting of nets in the offshore sector, logbook reporting of effort intensity and location and evaluations of risk through an ERA, these measures together with are likely to be considered at least a partial strategy to ensure that the fishery is unlikely to reduce structure and function of habitats to a point where there would be serious or irreversible harm.

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

There is evidence that the management strategy will work based on historical observer coverage onboard commercial vessels and confidence in the gear limitations reducing interaction with the seabed to negligible levels. Additionally, the ERA for the fishery concluded that there was a negligible interaction by the fishing gear with bottom habitats (Zeller and Snape 2006). This information provides some objective basis for confidence that the partial strategy will work.

CRITERIA: (iii) Information is adequate to determine the risk posed to the habitat by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage impacts on the habitat.

| (a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

|

The nature, distribution and vulnerability of habitat types within the Gulf of Carpentaria have been characterised and mapped over several decades with much of the information compiled to support marine reserve planning (e.g. Heap et al, 2004; Post, 2006; DEWHA, 2007). Locations of fishing activity are well-known through logbook reporting and observer coverage. Given the largely passive nature of the fishing gear, the available information on habitats is known at a level of detail consistent with the nature and scale of the fishery.

| (b) Information and monitoring adequacy |

LOW RISK |

|

Information is adequate to broadly understand the nature of the main impacts of gear use on the main habitats, including spatial overlap of habitat with fishing gear. While the impacts of gillnets on habitat haven’t been explored explicitly the physical impacts of this passive gear type is likely to be negligible (e.g. Zeller and Snape, 2006).

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

2D: Ecosystems

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to the key elements of ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Ecosystem Status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Given the relatively limited impact on habitats, the main ecosystem impacts from the fishery are likely to come from the removal of target and byproduct species from the ecosystem. In particular, the removals of top order predators such as sharks are suggested to impact marine food webs (e.g. Myers et al. 2007). However, an ERA conducted on the fishery in 2006 suggested that the harvest rate of most species (including sharks) are at levels that would have a negligible impact on the ecosystem function in the GOC. Additionally, the ERA considered the low levels of bycatch in the fishery would also be having a negligible impact on ecosystem function (Zeller and Snape, 2006). To that end, it is at least likely that the UoA is unlikely to disrupt the key elements underlying ecosystem structure and function to a point where there would be a serious or irreversible harm. However, without additional information on some issues (e.g. impacts on target and main other species, ETP species), it is difficult to conclude this with a high degree of certainty.

CRITERIA: (ii)There are measures in place to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The measures in place to ensure that the fishery does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem function are the same as those listed above for target, non-target and ETP species. Specific measures were included in the PMS to monitor ecosystem components (e.g. target species, non-target species, ETP species, habitats) albeit not specifically for broader ecosystem impacts (e.g. impacts on trophic dynamics, biodiversity). The impacts of the fishery on some ecosystem components were assessed through an ERA (Zeller and Snape, 2006). Although the outcomes are now dated, the broad characteristics of the fishery are likely to have remained largely the same. The measures in place arguably take account of some of the potential ecosystem impacts from the fishery and are probably sufficient to meet the medium risk SG. The Queensland Government has undertaken to produce an updated ERA for the GOCIFFF by the end of 2020 as part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027 (DAF, 2017a).

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The ERA (Zeller and Snape, 2006) provides some objective basis for confidence that the partial strategy will work given its finding of negligible impacts by the fishery on the ecosystem, although the outcomes are now dated. Evidence available from commercial logbooks and historical observer coverage onboard commercial vessels provides additional evidence that existing management measures are limiting impacts on key ecosystem components (habitat, non-target finfish species and systematic removal of top order predators) to negligible levels (e.g. Halliday et al. 2001). Nevertheless, there are weaknesses in some in reporting/monitoring of some ecosystem components (ETP, discards) and accordingly, we have scored this indicator medium risk.

CRITERIA: (iii) There is adequate knowledge of the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem.

| (a) Information quality |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The structure and function of the main elements of the northern Australian ecosystem has been relatively well studied, with much of the information compiled to support marine reserve planning processes (e.g. NOO, 2004; Zeller and Snape, 2006; DEWHA, 2007; 2008a; 2008b) or fisheries management (e.g. Bustamante et al, 2010). However, concerns about the quality of some logbook reporting (e.g. SOCI) and the absence of independent monitoring of some ecosystem components (e.g. discards, ETP) means current information is not sufficient to detect increased risk to them.

| (b) Investigations of UoA impacts |

LOW RISK |

|

The main impacts of the fishery on the ecosystem have been investigated in the 2006 qualitative ERA and there has been dedicated investigation of at least some ecosystem impacts of the UoA specifically (e.g. Halliday et al, 2001).

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

COMPONENT 3: Management system

3A: Governance and Policy

CRITERIA: (i) The management system exists within an appropriate and effective legal and/or customary framework which ensures that it:

- Is capable of delivering sustainability in the UoA(s); and

- Observes the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom of people dependent on fishing for food or livelihood.

| (a) Compatibility of laws or standards with effective management |

LOW RISK |

|

The Queensland Government and QFJA management and legislative framework is consistent with local, national or international laws or standards that are aimed at achieving sustainable fisheries.

Sections 61-70 of the Commonwealth Fisheries Management Act 1991 set out the establishment, functions, administration and reporting requirements for Joint Authorities. Part 7 of the Queensland Fisheries Act 1994 sets out complementary State legislation and other matters relating to the establishment, functions, administration and reporting requirements of the Joint Authority and the management of Joint Authority fisheries in Queensland.

The QFJA is established in the Arrangement between the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland in relation to the Fishery for Northern Demersal and Pelagic Fish in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The 1995 arrangement provides, among other things, that the relevant commercial fisheries be managed under Queensland law. Representatives of the Northern Territory Government may act as observers at meetings of the QFJA to ensure coordination between jurisdictions (e.g. QFJA, 2014).

There is a further arrangement between the Commonwealth and the State of Queensland, in relation to commercial fishing for Grey Mackerel in the Gulf of Carpentaria, under section 71 of the Fisheries Management Act 1991 and section 132 of the Fisheries Act 1994 of Queensland. The 2003 arrangement provides, among other things, that the commercial fishery for Grey Mackerel also be managed by the QFJA under Queensland law.

| (b) Respect for Rights |

LOW RISK |

|

The rights of Aboriginal persons to fish for a customary purpose are recognized in the Queensland Fisheries Act and subordinate legislation. The rights of customary fishers are recognised by the s14 exemption in the Fisheries Act that allows for an “Aborigine or Torres Strait Islander” to take fish for “the purpose of satisfying a personal, domestic or non-commercial communal need”. Additional customary rights may be sought under Commonwealth Native Title legislation.

CRITERIA: (ii) The management system has effective consultation processes that are open to interested and affected parties. The roles and responsibilities of organisations and individuals who are involved in the management process are clear and understood by all relevant parties.

| (a) Roles and Responsibilities |

LOW RISK |

|

The roles and responsibilities of the main people (e.g. Fisheries Minister, Deputy Director General, QFJA members) and organisations (DAF) involved in the management of the GOCIFFF are well-understood, with relationships and key powers explicitly defined in legislation (e.g. Qld FA) or relevant policy statements. The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland is responsible for the day-to day management of the fishery. Accountability relationships between the main agencies and their responsible Ministers are clear. Compliance functions are carried out primarily by the Queensland Boating and Fisheries Patrol (QB&FP).

| (b) Consultation Process |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Consultation occurs either directly with license holders on operational issues affecting the fishery and/or through a number of commercial sector bodies (e.g. QSIA, Gulf of Carpentaria Commercial Fishermen’s Association, the Fishermen’s Portal). The existing system for consultation includes both statutory and non-statutory opportunities for interested stakeholders to be involved in the management system. Notwithstanding that, the management system does not have established processes that regularly seek and accept relevant information from all interested and affect parties, including local knowledge.

The Queensland Government has committed to strengthening stakeholder engagement processes as part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027 (DAF, 2017a).

CRITERIA: (iii) The management policy has clear long-term objectives to guide decision making that are consistent with the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2, and incorporates the precautionary approach.

| (a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|

Day to day management of the GOCIFFF is undertaken according to Queensland law. The overarching objectives for the management of Queensland fisheries set out in the Fisheries Act appear implicitly consistent with the outcomes expressed in Components 1 and 2 and some are explicitly set out in the Act. The Fisheries Act 1994 states that its (1) ‘main purpose’ is to ‘provide for the use, conservation and enhancement of the community’s fisheries resources and fish habitats in a way that seeks to— (a) apply and balance the principles of ecologically sustainable development; and (b) promote ecologically sustainable development. The Act also states that:

- ecologically sustainable development means ‘using, conserving and enhancing the community’s fisheries resources and fish habitats so that— (a) the ecological processes on which life depends are maintained; and (b) the total quality of life, both now and in the future, can be improved’; and

Precautionary principle means that ‘if there is a threat of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of scientific certainty should not be used as a reason to postpone measures to prevent environment degradation, or possible environmental degradation, because of the threat’.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

3B: Fishery Specific Management System

CRITERIA: (i) The fishery specific management system has clear, specific objectives designed to achieve the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2.

| (a) Objectives |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Higher levels objectives consistent with Components 1 and 2 are contained in the overarching legislation (Fisheries Act 1994) and implicit within the management system. More specific objectives for key target, bycatch and protected species were included in the PMS for the fishery, although we understand monitoring against the PMS has been largely discontinued. The UoAs would be better positioned against this SI with explicit short and long term fishery specific objectives in place for the fishery.

CRITERIA: (ii) The fishery specific management system includes effective decision making processes that result in measures and strategies to achieve the objectives.

| (a) Decision making |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The Queensland Government Minister responsible for the fisheries portfolio has ultimate responsibility for the inshore components of the fishery and the QFJA has responsibility for the offshore components, albeit Queensland undertakes day-to-day management responsibility.

The most recent major changes in the fishery were introduced in November 2011 and included the creation of the N12 and N13 fishery symbols, a reduction in the total length of net in the fishery to limit effort increases on Grey Mackerel and sharks in offshore waters and a range of other more minor changes (e.g. standardising the opening and closing dates of the Barramundi seasonal closure). Changes to limit potential effort on grey mackerel were made in response to catch increases and concerns about the sustainability of this species identified in the 2006 ERA. Other changes made in recent years have included changes to commercial logbook formats to better record species identification of sharks (e.g. DEEDI, 2010b) and changes introduced in 2018 to limit catches of hammerhead sharks.

The extent to which the management system actively responds to all serious issues identified through research and monitoring in a timely manner is arguable – for example, available research and monitoring suggests that current levels of fishing mortality will likely lead to the Gulf of Carpentaria stocks of King Threadfin becoming recruitment overfished (Moore, 2011; Whybird et al, 2016) and it is not clear that the management system has responded yet in a timely and adaptive manner. However, the grey mackerel example provides some evidence that the management system responds to serious issues (e.g. dealing with potential unsustainable fishing) and takes account of the wider implications of decisions (e.g. DEEDI, 2010a). Nevertheless, given the long intervals between management change and other supporting processes such as ERAs it is not clear that the management system responds to all issues in a transparent, timely and adaptive manner required of the low risk SG. There is also limited evidence to date that the management system has responded to the recommendation in both the Leigh (2015) and Cortes (2016) to strengthen data collection in the shark sector.

As part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027, the Queensland Government has committed to “amending the fisheries legislation (Fisheries Act 1994 and Fisheries Regulation 2008) in 2018 to clarify the roles of the responsible minister and Fisheries Queensland, to ensure decision-making is at the appropriate level and is timely and evidence-based, and that rules can be changed via declaration as far as possible to ensure sufficient flexibility” (DAF, 2017a).

| (b) Use of the Precautionary approach | MEDIUM RISK |

The use of the precautionary approach is required under the Fisheries Act, however the evidence that the fishery is being managed in a precautionary manner is not comprehensive. For example, the extent to which current management measures are precautionary in the context of substantial uncertainty around the status of the Blacktip Shark stock is not clear. Moreover, there is no independent monitoring of ETP species interactions despite concerns about SOCI reporting and a relatively high risk rating for at least some ETP species (e.g. sawfish/river sharks; DoE, 2015). Accordingly, additional evidence of precautionary management would be required to meet the low risk SG for this SI.

| (c) Accountability and Transparency |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Some information on the fishery’s performance is available through the DAF website (summary of catch, stock status, species monitoring, 2006 ERA, annual reports), as well as through other websites (e.g. Commonwealth Department of Environment and Energy website; Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks website). Annual reports were previously produced assessing performance against the PMS for the fishery, however the most recent publicly available report was for the 2012 year. Where substantive management change is proposed a Regulatory Impact Statement is required to be released for public comment, setting out proposed changes, their justification and alternative options (e.g. DEEDI, 2010a). The activities of the QFJA are tabled in an annual report to Commonwealth parliament[1]. Annual meetings of the Gulf of Carpentaria Commercial Fishermen’s Association are held to coincide with the Barramundi seasonal closure. Government staff are usually invited to attend these meetings and provide explanations for management activity.

Nevertheless, some information does not appear to be publicly available at this stage (e.g. recent summaries of ETP species interactions; annual reports provided to the Commonwealth environment department).

[1] E.g. http://www.afma.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/QFJA-2013-14-tabled.pdf

CRITERIA: (iii) Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms ensure the management measures in the fishery are enforced and complied with.

| (a) MCS Implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Compliance and enforcement in the fishery are the responsibility of the Queensland Boating and Fisheries Patrol (QBFP). The MCS system comprises compulsory catch and effort reporting, licensing, risk assessments, at sea and port based inspections, intelligence gathering and both administrative penalties and prosecutions. Compliance statistics from the most recent ASR (2012 fishing year) suggest the system generally has the capacity to enforce relevant management measures, although there is concern in relation to the accuracy of SOCI reporting (e.g. DoE, 2015).

| (b) Sanctions and Compliance |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Sanctions to deal with non-compliance exist and appear to be consistently applied. In 2012, 68 commercial net fishing vessels were inspected with 7 offences detected (DAFF, 2014). DAF (2017b) reports that, in relation to shark finning specifically, from 2011-16, 270 commercial vessel inspections failed to detect a single finning offence. While no evidence of systematic non-compliance appears to be evidence in published compliance statistics for the fishery (e.g. DAFF, 2014), the main weaknesses against this SI is the concern in relation to the accuracy of SOCI logbook reporting. To that end, we have scored this SI medium risk.

The main source of illegal shark catch in Australia’s northern waters in recent times has come from small-scale Indonesian fishers targeting sharks for fins (e.g. Salini et al, 2007; Marshall, 2011). The number of apprehensions of illegal vessels rose steadily from the early 2000s, peaking in 2005-06 at 368 apprehensions (Marshall, 2011). Based on numbers and species composition from a sample of apprehended Indonesian vessels, Marshall (2011) estimated the total illegal harvest of sharks by Indonesian vessels in 2006 (the peak calendar year of illegal activity) was 680t, with species in the Blacktip Shark complex (C. tilstoni, C. limbatus) accounting for around 17% of the catch. Apprehensions have substantially decreased since that time with only 27 apprehensions in the 2008-2009 financial year. The decrease in illegal activity has been attributed to a number of factors including increased border security by the Australian Government, the global financial crisis, high petrol prices and new domestic policies (Marshall, 2011). Illegal catches are accounted for in stock assessments (e.g. Grubert et al, 2013).

CRITERIA: (iv) There is a system for monitoring and evaluating the performance of the fishery specific management system against its objectives.

There is effective and timely review of the fishery specific management system.

| (a) Evaluation coverage |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Performance of the management system has historically been monitored through the PMS, which sets out performance indicators for: target species, byproduct species and bycatch species (including ETP species) but not for habitat and ecosystem impacts (DPIF, 2008). However, we understand the monitoring against the PMS has been largely discontinued, with the most recent annual report available for the 2012 fishing year. Stock status of key target species are assessed at least biennially through the Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks process. One qualitative ecological risk assessment has been performed to assess the likely impacts of the fishery on non-target species and habitats (e.g. Zeller and Snape, 2006). As part of the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027, the Queensland government has committed to a range of measures which will likely strengthen ongoing evaluation of fishery’s performance including the introduction of harvest strategies, improved monitoring and data collection, improved stakeholder engagement and periodic ERAs (DAF, 2017a).

| (b) Internal and/or external review |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Some parts of the management system are subject to regular review (e.g. target stock status), while others appear to be subject to only occasional review (e.g. ecological risks). The fishery is also periodically assessed externally by the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Energy under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Recent assessments have been at 3 yearly intervals according to the fishery’s WTO declaration.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

Acknowledgements

This seafood risk assessment procedure was originally developed for Coles Supermarkets Australia by MRAG Asia Pacific. FRDC is grateful for Coles’ permission to use its Responsibly Sourced Seafood Framework.

It uses elements from the GSSI benchmarked MSC Fishery Standard version 2.0, but is neither a duplicate of it nor a substitute for it. The methodology used to apply the framework differs substantially from an MSC Certification. Consequently, any claim about the rating of the fishery based on this assessment should not make any reference to the MSC.