Moreton Bay Bug – Commonwealth Northern Prawn Fishery

Assessment Summary

Fishery Overview

The following summary of the fishery is adapted from Larcombe and Bath (2017):

The Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF) uses otter trawl gear to target a range of tropical prawn species. White banana prawn and two species of tiger prawn (brown and grooved) account for around 80 per cent of the landed catch. Byproduct species include endeavour prawns, scampi (Metanephrops spp.), bugs (Thenus spp.) and saucer scallops (Amusium spp.). In recent years, many vessels have transitioned from using twin gear to mostly using a quad rig comprising four trawl nets.

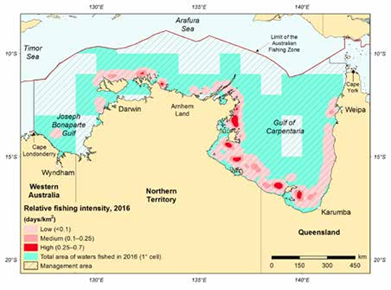

White banana prawn (Fenneropenaeus merguiensis) is mainly caught during the day on the eastern side of the Gulf of Carpentaria, whereas red-legged banana prawn (F. indicus) is mainly caught in Joseph Bonaparte Gulf (Figure 1). Tiger prawns (Penaeus esculentus and P. semisulcatus) are primarily taken at night (daytime trawling has been prohibited in some areas during the tiger prawn season). Most catches come from the southern and western Gulf of Carpentaria, and along the Arnhem Land coast. Tiger prawn fishing grounds may be close to those of banana prawns, but the highest catches come from areas near coastal seagrass beds, the nursery habitat for tiger prawns. Endeavour prawns (Metapenaeus endeavouri and M. ensis) are mainly a byproduct, caught when fishing for tiger prawns.

Figure 1: Relative fishing intensity in the Northern Prawn Fishery in 2016 (Source: Larcombe and Bath, 2017).

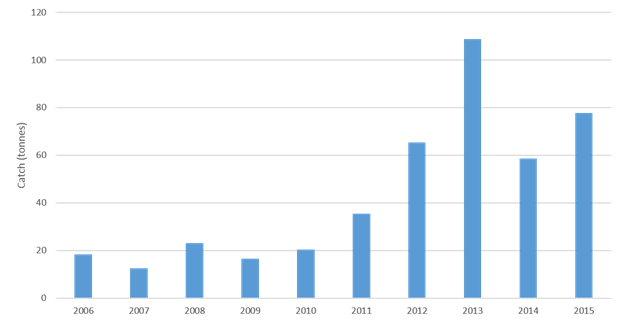

The NPF developed rapidly in the 1970s, with effort peaking in 1981 at more than 40 000 fishing days and more than 250 vessels. During the next three decades, fishing effort and participation were reduced to the current levels of around 7 500 days of effort and 52 vessels. Total NPF catch in 2016 was 5,807 t, comprising 5,432 t of prawns and 375 t of byproduct species (predominantly bugs, squid and scampi). Annual catches tend to be quite variable from year to year because of natural variability in the banana prawn component of the fishery (Figure 2).

Under an Offshore Constitutional Settlement (OCS) agreement between the Commonwealth, Western Australia, Northern Territory and Queensland governments, originally signed in 1988, prawn trawling in the area of the NPF to low water mark, is the responsibility of the Commonwealth through the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA).

The fishery has been certified against the Marine Stewardship Council standard for the main prawn species since 2012[1].

[1] https://fisheries.msc.org/en/fisheries/australia-northern-prawn/

Figure 2 Trends in Total Catch

Risk Scores

|

Performance Indicator |

Risk Score |

|

COMPONENT 1 |

|

|

1A: Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

OVERALL |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

COMPONENT 2 |

|

|

LOW RISK |

|

|

2B: ETP Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2C: Habitats |

LOW RISK |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

LOW RISK |

|

OVERALL |

LOW RISK |

|

COMPONENT 3 |

|

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW RISK |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

LOW RISK |

|

OVERALL |

LOW RISK |

Summary of main issues

- The NPF has been certified against the Marine Stewardship Council’s Fishery Standard for the main target prawn species since 2012.

- Moreton Bay Bugs are taken as a byproduct species in the NPF. No formal assessment of the stock has been undertaken, although quantitative estimates of acceptable biological catch (ABC) have been developed using independent trawl survey data. Catches in the last decade have remained well below the ABC estimate.

- There are currently no well-defined HCRs in place for Moreton Bay Bugs in the NPF, although the stock is subject to a minimum legal size and a precautionary trigger catch limit of 100t which triggers a review of available data to identify any sustainability issues if reached.

- The fishery is well placed against Component 2 and 3 PIs.

Outlook

| Component | Outlook | Comments |

| Target species | Stable | Catches have remained well below estimates of acceptable biological catch (ABC) for the past decade. Given Moreton Bay Bugs are taken as a byproduct and catch has remained well below ABC, there is limited incentive to undertake formal stock assessments and develop well-defined HCRs. |

| Environmental impact of fishing | Stable | No major changes are expected to Component 2 arrangements. |

| Management system | Stable | No major changes are expected to Component 3 arrangements. |

COMPONENT 1: Target fish stocks

1A: Stock Status

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing.

| (a) Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

No studies have been carried out on the biological stock structure of Australian Moreton Bay Bugs (Zeller et al, 2016). Given the uncertainty in stock structure, assessment of stock status is presented here at the management unit level.

Zeller et al (2016) report that “Northern Prawn Fishery (Commonwealth) trawl surveys were used to estimate the biomass of Moreton Bay Bugs in the Gulf of Carpentaria, from which an estimate of acceptable biological catch was derived. This assessment estimated the annual acceptable biological catch for Moreton Bay Bugs in the fishery at 1887 tonnes (t) (95 per cent confidence interval 1716–2057 t). Annual commercial catches have remained well below this (catch peaked at 120 t in 1998). Catches were 59 t in 2014 and 77 t in 2015.” On the basis of the above, they conclude that the stock is not overfished.

Given annual catches remain well below estimates of acceptable biological catch (ABC), it is highly likely that the stock is above the point of recruitment impairment. While there is less direct evidence the stock is fluctuating at or around BMSY, given the low catches over a long period of time in the context of the estimated ABC, there is a plausible argument that the current level of fishing mortality is unlikely to have reduced the stock below a level capable of producing MSY. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

1B: Harvest Strategy

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place.

| (a) Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

|

The harvest strategy for the NPF is structured around the targeted prawn species and is described in detail by Dichmont et al (2014) and MRAG Americas (2018).

Fishing mortality is managed through a combination of input controls (limited entry, seasonal closures, permanent area closures, gear restrictions and operational controls), which are implemented under the Northern Prawn Fishery Management Plan 1995.

To fish in the NPF operators must hold Statutory Fishing Rights (SFRs), which control fishing capacity by placing limits on the numbers of trawlers and the amount of gear permitted in the fishery. There are two types of SFRs: (i) a Class B SFR, which permits a boat to fish in the NPF; and (ii) a gear SFR, which limits the amount of net a fisher can use (Dichmont et al, 2014). The fishery is also subject to a range of spatial closures to protect seagrass beds and other sensitive habitats, as well as seasonal closures protect to small prawns, as well as to protect spawning individuals.

Levels of effort in the fishery are adjusted according to a formal harvest strategy structured around the two main ‘fisheries’: the ‘tiger prawn fishery’ and the ‘banana prawn fishery’ (Dichmont et al, 2014). In the tiger prawn fishery, the operational objective is to achieve maximum economic yield (MEY) with adjustments made as necessary to spatial and temporal closures, and/or gear to meet the MEY objective over a 7-year period. The outputs from a bio-economic model (which includes the biology of tiger and endeavour prawns, and key economic variables) are used to set the level of standardised effort for the fishery.

In the banana prawn fishery, the operational objective is to allow sufficient escapement from the fishery to ensure an adequate spawning biomass (based on historical data), and to achieve the maximum economic yield (MEY) from the fishery. The length of the main fishing season for banana prawns is adjusted according to a set of structured decision rules designed to achieve MEY. In-season management is provided for which aims at allowing a maximum season length in highly productive years, and reducing the season length in years of low production.

In addition to the controls on effort for the main target species, Moreton Bay Bugs are subject to a number of species specific management measures. These include a 60 mm minimum carapace width and a prohibition on the take of ‘berried’ female bugs (Dichmont et al, 2014). In addition, a 100t trigger limit applies, which if breached triggers a review of logbook and trawl survey data to establish that catches are sustainable. The trigger limit is highly conservative in the context of the acceptable biological catch (ABC) for Moreton Bay Bugs in the NPF of 1,887t (95% c.i. 1,716 – 2,057) calculated by Milton et al (2010) using independent trawl survey data. Catches have remained well below the ABC, with catch peaking in 2013 at 109t.

The fishery is monitored through a compulsory daily catch and effort logbook, as well as through an annual fishery independent trawl survey undertaken in January/February and a biennial trawl survey undertaken in June/July. The fishery is also subject to a crew member observer program and a scientific observer program. In 2016, crew member observers undertook 893 monitoring days (11.3% of fishing effort) and scientific observers undertook 103 monitoring days (1.3% of fishing effort) (Larcombe and Bath, 2017).

Although the harvest strategy for the NPF is designed around the main target species, estimates of sustainable catch levels for bugs have been made and existing harvest controls have been sufficient to consistently constrain catch well below those estimates. Catches continue to be monitored against a precautionary trigger point, which precipitates a review of available data if breached.

To that end, the harvest strategy could be expected to be responsive to the state of the stock (if reviews following a breach of trigger limits identified a sustainability concern) and all of the elements appear to work together to meet the stock management objectives reflected in criterion 1A(i). Accordingly, we have scored this SI low risk.

| Shark-finning |

NA |

CRITERIA: (ii) There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place.

| (a) HCR Design and application |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

There is currently no well-defined harvest control rule for Moreton Bay Bugs, although the stock is subject to a trigger limit under the NPF harvest strategy which precipitates a review of available data if breached (Dichmont et al, 2014). NPRAG (2017) noted the trigger limit was exceeded in 2016, but concluded bugs weren’t being targeted and there was no concern for the stock.

Given catches have remained well below the estimated ABC for the stock, and the fact that HCRs have been used extensively by AFMA in the NPF and other fisheries, there is a strong argument that generally understood HCRs are in place and tools are available (e.g. spatial/temporal closures, adjustments to MLS) which could be expected to reduce exploitation if PRI was approached. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

1C: Information and Assessment

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy.

| (a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|

Moreton Bay Bugs are distributed along the tropical and subtropical coast of Australia from northern New South Wales to Shark Bay in Western Australia. No studies have been carried out on the biological stock structure of Australian Moreton Bay Bugs. The two species (Thenus australiensis and T. parindicus) have overlapping distributions, may be trawled together, are undifferentiated in the catch and are thus typically assessed together (Zeller et al, 2016).

Although information on stock structure is limited, a range of information exists to inform the harvest strategy. For example, Milton et al (2010) used independent trawl survey data to estimate acceptable biological catch levels for the stock within the NPF. They also used Bayesian methods to undertake preliminary evaluations of a range of alternative management approaches including changes to the minimum legal size and levels of compliance. A number of studies have characterised the biology of Moreton Bay Bugs including growth, mortality and reproductive potential (e.g. Courtney, 1997; Stewart et al, 1997).

Fleet composition is well understood and sufficient data are collected to support the harvest strategy (i.e. MLS and trigger limits) including catch and effort levels (verified by scientific and crew member observers), discards, vessel details and spatial effort coverage through VMS data.

| (b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Moreton Bay Bugs are a byproduct species in the NPF, so stock abundance is not monitored in the same way as the main target species. The main ‘HCR’ in the fishery is the 100t catch trigger limit in the harvest strategy which precipitates a review of available information if breached. The trigger limit takes into account Milton et al’s (2010) estimates of ABC and has been set at a precautionary level. Removals from the UoA are very well monitored through catch and effort logbooks, with independent estimates provided by crew and scientific observer programs. Given the nature of the stock and absence of similar fisheries in the area, there are likely to be few if any removals from other fisheries. To that end, UoA removals are monitored and at least one indicator (catch) is monitored consistent with the ‘HCR’ for the stock. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk. Milton et al (2010) suggest that the NPF prawn monitoring surveys may provide a reliable index of Moreton Bay Bug abundance, although this stock is not regularly included in normal analysis of surveys results.

CRITERIA: (ii) There is an adequate assessment of the stock status.

| (a) Stock assessment |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

No formal quantitative assessment of the NPF Moreton Bay Bug stock exits, although Milton et al (2010) produced estimates of biomass and a possible ‘acceptable biological catch’ based on data from independent prawn surveys run between 2005 and 2007. They noted that they attempted to conduct a stock assessment using biomass dynamics models, however the models failed to produce reliable and reasonable results. The main difficulties included the short data timeseries (1998 – 2007) in the commercial logbooks, the fact that commercial logbook records are not a reliable proxy for species occurrence because fishers may not always retain byproduct when they catch them and as non-target species the catch and CPUE may not be a reliable index for abundance. Milton et al (2010) concluded that because catch has been well below their estimates of ABC, catches do not need close monitoring by managers unless fishing practices change dramatically. Accordingly, estimates of ABC have not been updated since.

In addition to the monitoring of catch against the trigger point in the harvest strategy, the stock is also subject to regular ‘weight of evidence’ assessments as part of the FRDC Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks report (e.g. Zeller et al, 2016). These assessments classify status according to generic categories (e.g. ‘sustainable’, ‘overfished’, etc). Given that these assessments estimate status relative to generic categories and status in the NPF Harvest Strategy is assumed to be sustainable if catch remains below the 100t trigger level, there is an argument that assessments are undertaken which estimate status relative to generic ‘reference points’ which are appropriate to the species category. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

| (b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Milton et al (2010) note that theirs was the first attempt to undertake some form of quantitative assessment of Moreton Bay Bugs in the NPF and also used new methods. As a result, there are several uncertainties in the assessment. Attempts were made to account for some uncertainties (e.g. by using multiple values for natural mortality), although other types of uncertainty may not yet be accounted for. The ‘weight of evidence’ approach used for the FRDC Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks report attempts to account for uncertainty by drawing from multiple sources of available information. The outcomes of these assessment are subject to peer review.

Note: The NPF has been certified against the Marine Stewardship Council standard for the main prawn species since 2012. The certification covers the full geographic scope of the fishery. Assessments against Components 2 and 3 of this assessment are based on the information provided in the NPF’s MSC Public Certification Report (MRAG Americas, 2018). Unless otherwise specified, the Component 2 information (and MSC scoring) is drawn from the assessment of the tiger prawn sub-fishery given the proportional catch of Moreton Bay Bugs is highest in this sector.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

2A: Other Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI.

| (a) Main other species stock status |

LOW RISK |

|

The NPF scored 90 and 100 for retained and discarded species status respectively in its 2018 MSC re-assessment.

For the tiger prawn sub-fishery (incorporating the brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn, blue endeavour prawn, red endeavour prawn UoAs), two main other species were assessed: brown tiger prawn and grooved tiger prawn. The most recent stock assessments for both species estimated biomass to be above the target reference point.

For discarded species MRAG Americas (2018) report that:

- “Tiger prawn trawling generally occurs close to the substratum and as a result selectivity of prawns is low and bycatch is high. Dell et al. (2009) estimated the bycatch volume for the tiger prawn subfishery as 20,073 t yr-1 ±568 SE, resulting in a bycatch to prawn ratio of 8:1. According to recent data from AFMA Scientific Observer Program, compiled by Fry & Miller (2016, Annex), bycatch in the tiger prawn subfishery accounted for about 66% and the bycatch to prawn ratio was 1.9:1.”

- “All the main bycatch species have been subject to a quantitative ecological risk assessment, the Sustainability Assessment for Fishing Effects (SAFE), in 2007 and re-assessed in 2010 using updated fishery data (Zhou, 2011). All these species scored low risk from the Tiger Prawn Subfishery. No species with percentage contributions between 2% and 5% catch biomass were found to be vulnerable, mainly because they are species with small sized individuals and high productivity and are widely distributed outside the fishing grounds. Thus, they do not classify as main. All species in this category were also assessed at ERA Level 2.5 (SAFE) and scored low risk from the fishery. In addition, all species of teleosts and elasmobranchs identified as potential bycatch were SAFE assessed (Zhou & Griffiths, 2008; Zhou et al., 2009a, Zhou, 2011)).”

“…there is a high degree of certainty that all main bycatch species are within biologically based limits and the tiger prawn subfishery does not pose a risk of serious and irreversible harm (none of these species scored medium or high risk).”

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

The tiger prawn UoAs for the NPF scored 95 and 100 for retained and discarded species management respectively in its 2018 MSC re-assessment.

For retained species in the tiger prawn sub-fishery, the assessment noted that:

- “Brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn, blue endeavour prawn and red endeavour prawn are mainly targeted in the tiger prawn subfishery and covered by the tiger prawn harvest strategy. These species are also retained species in the UoAs when they are not assessed as targets. The operational objective of the tiger prawn HS is to attain long-term maximum economic yield (MEY) from the tiger prawn subfishery overall. MEY is calculated as the biomass at the effort level in each year over a 7-year projection period that creates the biggest difference between the total revenue generated from tiger and endeavour prawns and the total costs of fishing for the tiger prawn fishery as a whole. The harvest strategy contains a comprehensive set of control rules for brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn and blue endeavour that feed into HS actions, including rules to cease fishing for the species where stock falls below limit reference point (0.5SMSY). The HS is designed to be responsive to the state of each species’ stock (except for red endeavour) and achieve objectives reflected in the target and limit reference points (Dichmont et al., 2014).”

- “There are no specific measures for red endeavour prawns although the harvest strategy that is in place for tiger prawn species and blue endeavour prawn is highly likely to benefit this species and to maintain it within its biologically based limits (Dichmont et al., 2014).”

For discarded species, the assessment noted that:

- “In accordance with the Fisheries Management Act (FMA) 1991 and Commonwealth Policy on Fisheries Bycatch 2000, all fishery management plans require the development and implementation of bycatch action plans (BAPs) to ensure that bycatch is reduced to a minimum (AFMA 2008b). The first BAP in the NPF was implemented in 1998 (first fishery to implement BAP in Australia), with the introduction of TEDs, BRDs, reduced effort and implementation of spatial and temporal closures (NPFI, 2015). Since then, more than 50% reduction in bycatch has been achieved and now NPFI is moving to the implementation of a Bycatch Strategy based on AFMA Bycatch and Discarding Workplan 2014-2016 (AFMA, 2014). The vision of this strategy is ” To reduce the capture of small fish and other bycatch in the Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF) by 30% within three years through a voluntary industry initiative” (NPFI, 2015).”

- “Regular risk assessments for bycatch species and on-going monitoring through fishery dependent (logbooks, CMOs) and independent (AFMA SO, CSIRO surveys) are also part of the bycatch management, ensuring that any changes in the level of risk will by identified and appropriate actions will be timely implemented.”

“Measures designed to manage the impact on bycatch specifically (a plan for 30% reduction, codes of practice, incentives, BRDs) represent a “strategy”, and it is understood how they work to achieve the required outcome (MSC, 2014 FCR v2, Table SA8, Definitions). These measures work together with other measures designed primarily to manage the impact on target species (effort control through gear restrictions and spatial closures) or ETPs (TEDs), to achieve an overall reduction in bycatch. In conclusion, there is a strategy to manage bycatch species in all six UoAs: brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn, blue endeavour prawn, red endeavour prawn, white banana prawn, red-legged banana prawn.”

| (b) Management strategy evaluation |

LOW RISK |

MRAG Americas (2018) concluded for retained species in the tiger prawn sub-fisheries that:

- “The tiger prawn HS (including brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn, blue endeavour prawn) has been tested using the NPF Management Strategy Evaluation (Dichmont et al., 2006a, Dichmont et al., 2006b, Dichmont et al., 2006c, Dichmont et al., 2008, and Dichmont et al., 2012a). The HS is designed to be responsive to the state of each stock and achieve objectives reflected in the target and limit reference points cumulatively for targeted and nontargeted retained catch. Testing supports high confidence that the strategy for tiger and blue endeavour prawns will work and this is valid for all six UoAs.”

- “There is some basis for confidence that the partial strategy for red endeavour prawn will work based on information directly about the fishery and the species involved: low overlap of the species with the NPF fishing grounds (Crocos et al., 2001), the low risk score from both tiger and banana fisheries (Griffiths et al., 2007), consistent low catches since 1998 (Larcombe et al., 2016), and ongoing fishery independent surveys (Kenyon et al., 2016).”

For discarded species, MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that “Testing supports high confidence that the strategy will work in all six UoAs. Since the implementation of the first BAP in the NPF, in 1998, with the introduction of TEDs, BRDs, reduced effort and implementation of spatial and temporal closures, more than 50% reduction in bycatch has been achieved (NPFI, 2015). Moreover, the breakthrough achievement with the newly approved BRD, Kon’s Covered Fisheyes (NORMAC, 2017), which reduces bycatch with more than 30% and at the same time increasing target catch, gives confidence that the uptake of this device by the fishing operators will be high and this will work towards achieving the goal of the new NPFI Bycatch Strategy.”

| (c) Shark-finning | NA |

CRITERIA: (iii) Information on the nature and amount of other species taken is adequate to determine the risk posed by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage other species.

| (a) Information |

LOW RISK |

The tiger prawn sub-fisheries of the NPF scored 100 and 100 for retained and discarded species information performance indicators respectively in its 2018 MSC re-assessment.

For retained species, MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “A comprehensive data collection program has been established for the NPF to ensure reliable information is available on which to base management decisions. Information is collected through fishery dependent and independent programs on all retained species (target and non-target) taken in the NPF.” Information sources include:

- NPF-wide Daily Catch & Effort logbooks;

- fishery independent research, including annual fishery independent surveys for target species (brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn, blue endeavour prawn, red endeavour prawn, king prawn, white banana prawn) and byproduct (bugs, squid, cuttlefish, scallop); and

- the AFMA Scientific Observer program which collects data on species that are on the NPF priority list.

In addition, all retained species are subject of Ecological Risk Assessments.

Overall, they concluded that “the available information is adequate to support a strategy to manage retained species, and evaluate with a high degree of certainty whether the strategy is achieving its objective, for all UoAs.”

For discarded species, MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that:

- “Information is sufficient to quantitatively estimate the outcome status with respect to biologically based limits with high degree of certainty, in all six UoAs because bycatch species identified in the three subfisheries have been assessed quantitatively in risk assessments SAFE (teleosts and elasmobranchs) and in susceptibility and recoverability of benthic biodiversity and trawl impact studies for invertebrates”.

“Information is adequate to support a strategy to manage bycatch species, and evaluate with a high degree of certainty whether the strategy is achieving its objective in all three subfisheries.”

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

2B: Endangered Threatened and/or Protected (ETP) Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species.

The UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

LOW RISK |

|

The two tiger prawn UoAs in the NPF scored 90 for the ETP species status PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) noted that while a large number of ETP species occur in the area of the NPF, those most likely to interact with the fishery are marine mammals, marine turtles, sea snakes, sawfish, syngnathids (seahorses, seadragons, pipehorses and pipefish), solenostomids (ghost pipefish) and seabirds. The assessment concluded that, for each of these groups, there is a high degree of certainty that the effects of each of the six UoAs are within limits of national and international requirements for protection.

The assessment also concluded that, for marine turtles, marine mammals and seabirds, there is a high degree of confidence that there are no significant detrimental direct effects on these species.

For sea snakes, the assessment noted that sea snakes continue to be caught in significant numbers in all three subfisheries, although a high proportion are released alive (75%-80%). SAFE results showed that the estimated fishing mortalities for sea snake species that interact were lower than the minimum unsustainable fishing mortality (set at natural mortality) and lower than maximum sustainable fishing mortality (set at 0.5 natural mortality). Overall, the assessment concluded that “direct effects from any of the six UoAs are highly unlikely to create unacceptable impacts to sea snake species, although some uncertainty remains, since the interactions are not reported at species level.”

- For sawfish, in the tiger prawn subfishery, in a five-year period (2011-2015), 1219 sawfish interactions (yearly average = 244) were reported, with 75% of the animals released alive. The narrow sawfish (Anoxypristis cuspidata) was the most common sawfish species recorded in the NPF – around 97% of all sawfish captured during monitoring programs were from this one species, thus, it is very likely that most “unidentified” sawfish interactions are with this species. This species is not listed as vulnerable and it is not included in the sawfish and river sharks recovery plan (DoE, 2015). The assessment noted that “Sawfish species were risk assessed at ERAEF level 2, PSA and 2.5, SAFE (Griffiths et al., 2007; Zhou & Griffiths in 2008; Zhou in 2011, Zhou et al., 2015. Although sawfish species scored as high risk at PSA, at SAFE, which is a more quantitative assessment, using species attributes and the actual fishing impact, sawfish scored low risk, even when the uncertainty was considered (90% Confidence Interval).” Overall, MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that there is a high degree of confidence there are no significant direct effects from any of the six UoAs on narrow sawfish. For other species of sawfish, they concluded that “direct effects from any of the six UoAs are highly unlikely to create unacceptable impacts to the other three sawfish species, especially to green sawfish which is the second commonly caught, although some uncertainty remains, since not all the interactions are not reported at species level.”

For syngnathids and solenostomids, the assessment noted that:

- “most syngnathids interactions occur in the tiger prawn subfishery (62 annual average in 2011- 2015), while in the white banana prawn subfishery this are very rare, with a maximum of three per year. No interactions with syngnathids and solenostomids were reported in the redlegged banana subfishery.”

- “At the level 2.5 assessment, SAFE, only the species that have been recorded as captured by the fishery before 2007 were included Trachyrhamphus longirostris and Hippocampus queenslandicus and Filicampus tigris (Griffiths et al., 2007). Currently, H. queenslandicus are H. spinosissimus are considered same species. At SAFE assessment syngnathid species scored low risk from tiger prawn and banana prawn subfisheries cumulatively (Zhou & Griffiths, 2008, Zhou, 2011). All syngnathids and solenostomids that occur in the NPF area have wide distributions (although maybe patchy) in unfished areas and most species have preference for structured habitats (usually seagrass beds or reef habitat) that occur within permanently closed areas. Also, tiger prawn subfishery’s footprint is very low compared to the NPF managed area, NPF trawl footprint currently being about 1.6%.”

Overall, MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that for the most commonly caught synghnathid, T. longirostris, there is a high degree of confidence that there are no significant detrimental direct effects of the tiger prawn subfishery. For all the other species of syngnathids and solenostomids, direct effects from brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn, blue endeavour prawn and red endeavour prawn UoAs are highly unlikely to create unacceptable impacts, although difficulty in identifying species means there is higher uncertainty about species distributions and biology, and possibility of localised depletions.

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

- meet national and international requirements; and

- ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

All UoAs scored 95 for the ETP species management PI in the NPF 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that:

- “ETP species are managed in the NPF within the Bycatch Strategy (NPFI, 2015) which conforms to the latest Bycatch and Discarding Workplan (AFMA, 2014a) and extends the NPF Harvest Strategy (Dichmont et al., 2014).”

- “With the introduction of the NPF Bycatch Strategy, the NPF adopted a comprehensive strategy that focuses on ETP and “at risk species”, plus addresses bycatch reduction overall.”

“Management actions are informed by fishery dependent and fishery independent monitoring. Data from monitoring programs is regularly analysed and reported: bycatch and ETPs sustainability reports (every three years, e.g. Fry et al., 2015), integrated prawn monitoring reports (for the NPF prawn monitoring program in GoC, every two years, e.g. Kenyon et al., 2015), BRD performance assessments (next one in 2018, source: NORMAC, 2017). The information obtained from monitoring and research studies is used to regularly assess the risk from each subfishery to the affected species, including ETPs, through ecological risk assessments within ERAEF ranked risk framework developed jointly by AFMA and CSIRO (Griffiths et al., 2007, Zhou & Griffiths, 2008, Zhou et al., 2009, Zhou, 2011, Zhou et al., 2015). A revision of SAFE assessments is scheduled to be completed in 2017. Any identified increase in risk for any ETP species would trigger as response, revision of the risk level by the Bycatch Subcommittee and expert panel and update the NPF priority list. Nevertheless, AFMA and NPFI are proactive (not waiting for an increase in risk) in their ongoing efforts to gear innovations and improvement of the mitigation measure to ensure the effects of the three subfisheries are above the national and international requirements (see Table 14). Defined and measurable performance indicators specific for ETP species, and milestones, are presented …. The strategy is tested through testing the TEDs and BRDs performance on reducing ETP interactions, as well as assessing the status of the affected populations through monitoring and sustainability assessments.”

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that:

- “The strategy is mainly based on information directly about the fishery and/or species involved. The strategy is based on information from ongoing monitoring programs, regular sustainability assessments for the affected species (Fry et al., 2015), integrated monitoring reports on ETPs catch rate distributions in the GoC (Kenyon et al., 2016), ecological risk assessments (Griffiths et al., 2007, Milton et al., 2008b, Zhou & Griffiths, 2008, Zhou et al., 2009, Zhou, 2011), gear modifications (TEDs and BRDs) innovations testing (scientific and commercial testing) (Brewer et al., 2006, Burke et al., 2012). ETP populations trends and subfisheries’ impacts (monitoring, risk assessments, sustainability assessments) are based on both, qualitative and quantitative information. BRD and TED testing provide quantitative quantify the actual reduction in ETP catch. The strategy is mainly based on information directly about the fishery and/or species involved, and a quantitative analysis supports high confidence that the strategy will work.”

“There is clear evidence that the strategy is being implemented successfully.”

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

- information for the development of the management strategy;

- information to assess the effectiveness of the management strategy; and

- information to determine the outcome status of ETP species.

| (a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|

All UoAs scored 85 for the ETP species information PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that a number of monitoring programs are in place including fishery-wide (including all three subfisheries) daily catch and effort logbook program under which interactions with ETPs are required to be recorded, scientific and crew member observer programs, independent pre-season surveys (NPF prawn monitoring program) which collect data on ETP catch rates, and a gear monitoring program to monitoring program to monitor vessel fishing power and TED/BRD configurations.

They noted that “data from monitoring programs is regularly analysed and reported: bycatch and ETPs sustainability reports (every three years, e.g. Fry et al., 2015), integrated prawn monitoring reports (for the NPF prawn monitoring program in GoC, every two years, e.g. Kenyon et al., 2015), BRD performance assessments (next one in 2018, source: NORMAC, 2017). The information obtained from monitoring and research studies is used to regularly assess the risk from each subfishery to the affected species, including ETPs, through ecological risk assessments within ERAEF ranked risk framework developed jointly by AFMA and CSIRO (Griffiths et al., 2007, Zhou & Griffiths, 2008, Zhou et al., 2009, Zhou, 2011, Zhou et al., 2015). A revision of SAFE assessments is scheduled to be completed in 2017. Sufficient information is available to allow fishery related mortality and the impact of fishing from all six UoAs to be quantitatively estimated for all ETP species.”

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

2C: Habitats

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to habitat structure and function, considered on the basis of the area(s) covered by the governance body(s) responsible for fisheries management

| (a) Habitat status |

LOW RISK |

|

The tiger prawn UoAs scored 80 for the habitat status PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that:

- “At the 2007 NPF ERAEF, photographic data, geomorphic unit mapping, literature, and expert opinion were used to classify 157 fine scale habitat types on the basis of substratum, geomorphology, and dominant fauna. Out of the 157 habitat types, only 50 were subject to trawling. No habitats were found to be at high risk and 17 of the habitats where trawling can occur were assessed to be at medium risk. Most of these habitats contained seagrass that was not protected at the time of writing the ERA report. These were coastal margin habitats (0-25 m), which also include several soft sediment seabed types but which were dominated by seagrass communities which were not in protected areas (Griffiths et al., 2007).“

- “More recent benthic impact studies did not find a significant overall impact at current levels of trawling (Bustamante et al., 2010), although some habitat-forming species may be vulnerable to trawling.”

“Considering all available information, the tiger prawn subfishery (brown tiger prawn, grooved tiger prawn, blue endeavour prawn and red endeavour prawn UoAs) is highly unlikely to reduce habitat structure and function to a point where there would be serious or irreversible harm. There is evidence of reduction in the overall impact from the tiger prawn subfishery (Bustamante et al., 2010), although vulnerable habitat-forming species may be affected at local scale.”

[1] CMR = Commonwealth Marine Reserve

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the habitats.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

The tiger prawn UoAs scored 100 for the habitat management PI in the 2018 NPF MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “Habitat impacts are managed by footprint control. This is realised through a system of spatial and temporal closures adopted by the NPF to protect vulnerable habitats such as seagrass beds and coral and rocky reefs, as well as to address economic objectives of the fishery. About 19.6% of the NPF area (0‐150 m) is permanently closed in CMRs, ~0.2% in MPAs and 0.7% under fishery regulation — the total closed is 20.5% (Pitcher et al., 2016). Furthermore, the entire fishery is closed for 5.5 months each year. Another important measure was the reduction in fishing effort from 286 vessels in 1981 to 52 vessels in 2009. The annual footprint of the NPF trawl fishery is currently1.6% overall. The most affected habitat is the tiger prawn main habitat where most fishing effort from tiger prawn subfishery occurs. However, the trawl footprint here is low, currently about 13%, and it is not expected to increase. There is a strategy for managing the impact of the fishery on habitat types for all six UoAs.”

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that “Evidence that this strategy works and achieving its objective can be drawn from studies of trawl impact on biodiversity. Moreover, only a very small percentage of the NPF managed area is trawled, in areas with high natural variability and disturbance thus, impact from sources other than prawn fishing are likely to be more significant for the changes in the structure and function of the habitats in the NPF managed area. Haywood et al (2005) found that the state of the habitats impacted by trawling in the NPF is not a steady state that favours the fast growing or ‘weedy’ species over the slow growing ones but a highly dynamic one in which the seabed biota is changing in response to factors other than trawling. Moreover, simulation of the food web processes demonstrated that the reduction of fishing (from 286 vessels in 1981 to 52 vessels in 2009) has resulted in clear reductions of the overall impacts on biomass (bycatch) and trophic levels, this including the reduction of overall impacts on the structure and function of the habitat. Testing supports high confidence that the strategy will work, based on information directly about the fishery and habitats involved, for the NPF overall (all six UoAs).”

CRITERIA: (iii) Information is adequate to determine the risk posed to the habitat by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage impacts on the habitat.

| (a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

|

The tiger prawn UoAs scored 80 for the habitat information PI in the 2018 NPF MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “Although the distribution of the habitat types was possible to be predicted, comprehensive, fine scale habitat mapping is not available for habitats in the NPF managed area. The vulnerability of all potentially occurring habitats was assessed at ERA and habitats that occur on trawling grounds scored low risk (Griffiths et al., 2007). Vulnerable habitat forming species may occur in places potentially accessible to trawling and may be at risk at least locally within assemblages, if not at regional landscape scale (Pitcher et al., 2016). This information is less relevant for the white banana subfishery where fishing is off the seabed, in the water column, thus, vulnerable habitat is not susceptible to direct impact.

The nature, distribution and vulnerability of all main habitat types in the fishery are known at a level of detail relevant to the scale and intensity of the fishery and this is valid for all six UoAs. … The distribution of habitat types is not known over their range at fine scale, thus particular attention to the occurrence of vulnerable habitat types on trawl grounds cannot be applied, even though all known vulnerable habitat types occur within permanently closed areas.”

| (b) Information and monitoring adequacy |

LOW RISK |

|

On the basis of the available information, MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that “The effects of trawling on benthic biodiversity and habitats has been studied in detail and this research offers reliable information on the nature of the impacts and on the spatial extent of the interaction, the timing and the location of use of gear. The sustainability of the benthic species and communities was studied based on productivity and susceptibility attributes. Recoverability rates and depletion rates were studied and different scenarios of increasing/decreasing fishing effort, as well as modifying the spatial management were modeled (Hill et al., 2002, Haywood et al., 2005, Bustamante et al., 2010). Also, habitat types were identified and risk assessed. However, these studies focused on the Gulf of Carpentaria. There is a higher uncertainty about the nature of the impact in JBG (red-legged banana prawn subfishery), although the fishing effort in this subfishery is currently very low and habitat information is available (Przeslawski et al., 2011). Habitat ranges are only predicted and no comprehensive habitat mapping is available either in the GoC or JBG. Sufficient data are available to allow the nature of the impacts of the fishery (all six UoAs) on habitat types to be identified and there is reliable information on the spatial extent of interaction, and the timing and location of use of the fishing gear but the physical impacts have not been fully quantified.”.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

2D: Ecosystems

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to the key elements of ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Ecosystem Status |

LOW RISK |

|

All UoAs in the NPF scored 100 for the ecosystem status PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that:

- “The impacts of trawling on the ecosystem have been studied in-depth in the GoC, the area with the highest trawl footprint (approx. 2.5%, estimated from Pitcher et al., 2016). For the other two regions, the trawl footprint is too small compared to the spatial extent of the ecosystem (0.8% north of Arnhem Land, and 0.6% of JBG estimated from Pitcher et al., 2016) to pose a risk of serious and irreversible harm to the structure and function of the ecosystem. In addition, fishing occurs in areas with high natural disturbance (i.e. frequent cyclones) and the effects of prawn fishing would be undistinguishable.”

“Ecosystem modelling studies (Griffiths et al., in Bustamante et al., 2010, Annex 9) have shown that even though prawn trawling clearly impacted the GoC ecosystem, the substantial reduction in the fishing effort and in trawl footprint led to changes in the positive direction. The fast response to these management actions shows the resilience of the ecosystem. The MSE for ecosystem impacts modeled scenarios (Dichmont et al., in Bustamante et al., 2010) have shown that the introduction of MPAs had the potential to protect biodiversity overall and especially some of the more susceptible ETPs such as sawfish and sea snakes, resulting in increased biomass in the MPAs closed areas. Currently, about 20% of the NPF managed area is closed to trawling in CMRs and MPAs, including previously trawled areas. This is much higher than the current annual and multiannual trawl footprint. Considering all the ecosystem impact research focused on the impacts from the tiger prawn subfishery and ERAEF assessments, there is evidence that the tiger prawn subfishery, at the current levels of activity, is highly unlikely to disrupt the key elements underlying ecosystem structure and function to a point where there would be a serious or irreversible harm.”

CRITERIA: (ii) There are measures in place to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

All UoAs in the NPF scored 100 for the ecosystem management PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “the NPF Management Plan defines a long-term management objective consistent with achieving the outcomes expressed by MSC PI 2.5.1. Objective 1, Ensure the utilisation of the fishery resources within the Northern Prawn Fishery is consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development and the exercise of the precautionary principle (AFMA, 2012a). The combined measures to minimize impacts on each component of the ecosystem ensure that the UoCs do not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the structure and function of the ecosystem.

An important measure to reduce overall for ecosystem impact in all, tiger prawn, white banana prawn and red-legged banana prawn subfisheries, was the significant progressive reduction in fishing effort from 286 vessels in 1981 to 52 vessels in 2009. Currently, the most important measure is maintaining a low trawl footprint, which is the main measure in the habitat management strategy. The monitoring of the footprint allows a risk-based approach to evaluating potential impacts on the ecosystem. Management strategies defined for each of the other ecosystem components are in place, i.e. harvest controls and limits on retained catch, measures to minimise bycatch and ETP interactions, as presented in previous sections. These strategies combined together constitute a management plan to mitigate impacts from each subfishery on the ecosystem overall.”

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) concluded that “Ecosystem modelling indicates that the trawling activities in Gulf of Carpentaria in the last 40 years did not affect overall biodiversity and cannot be distinguished from other sources of variations in community structure (Dichmont et al., in Bustamante et al., 2010, Annex 9).”

CRITERIA: (iii) There is adequate knowledge of the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem.

| (a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

|

All UoAs in the NPF scored 100 for the ecosystem information PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that:

- “long-term data sets are available for the NPF. Whilst most of the data have been collected for stock assessment of the target species, there have also been several studies that directly or indirectly provide data to identify key components of the ecosystem. Such studies have quantified levels of (i) by-product; (ii) by-catch; and (iii) interactions with ETPs. Several research projects have been conducted to obtain information on the impacts of prawn trawling on habitats and ecosystem (Hill et al., 2002, Haywood et al., 2005, Bustamante et al., 2010).”

- “The main project to approach trawling effects on ecosystem (Bustamante et al., 2010) developed a multidisciplinary approach to quantitatively evaluate the ecological effects of trawling on the ecosystem, and delivered analytical tools to evaluate such effects in spatially explicit contexts under multiple management objectives.”

- “Information continues to be collected on the impacts of the fishery on the key ecosystem components at a sufficient level to detect any increased risk and update the risk assessment. Fishers are required to report all retained species catches, effort, any ETP species interactions and fishing location in daily logbooks.”

“Information is sufficient to support the development of strategies to manage ecosystem impacts, especially the impacts from the tiger prawn subfishery and from the white banana prawn subfishery in GoC.”

| (b) Investigations of UoA impacts |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “An ERAEF risk assessment has been conducted by CSIRO in 2007, assessing all ecosystem components at various levels: Level 1, SICA, for all components, Level 2, PSA, for target species, byproduct species, and ETPs that are potentially caught (Griffiths et al., 2007). These levels of assessment were undertaken separately for the tiger prawn fishery (in tiger prawn season) and banana prawn fishery (in banana prawn season). Because it operates in both seasons, the risk from the red-banana prawn subfishery was assessed together with the risk from tiger prawn subfishery during the tiger prawn season and together with the risk from the white banana prawn subfishery during the banana season. A higher, more quantitative, level of assessment, SAFE, level 2.5, was applied for teleosts and elasmobranchs separately in the Gulf of Carpentaria (tiger prawn subfishery and banana prawn subfishery, Zhou & Griffiths, 2009; Zhou et al., 2009; Zhou, 2011) and in the Joseph Bonaparte Gulf (red-legged banana prawn subfishery Zhou et al., 2015). SAFE assessment was also applied for species of sea snakes incidentally caught in the NPF overall (Milton et al., 2008b). An ecosystem model was developed for the GoC and main interactions between the tiger prawn subfishery (the subfishery with highest levels of impact on ecosystem) and ecosystem elements have been investigated (Bustamante et al., 2010). Present information suggests that main ecosystem impacts are known and there is sufficient detail in the research to infer main interactions from the existing information and have been investigated in detail for the mainly for the tiger prawn subfishery. Given the very low levels of impact from the other two subfisheries compared to the impacts from the tiger prawn subfishery, the focus on studying the latter is justified and precautionary. Main interactions from the withe banana subfishery and red-legged banana subfishery respectively with the ecosystem elements, can be inferred from the existing information and from these being studied in detailed for the tiger prawn subfishery.”

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

COMPONENT 3: Management system

3A: Governance and Policy

CRITERIA: (i) The management system exists within an appropriate and effective legal and/or customary framework which ensures that it:

- Is capable of delivering sustainability in the UoA(s)

- Observes the legal rights

- Created explicitly or established by custom of people dependent on fishing for food or livelihood; and

- Incorporates an appropriate dispute resolution framework.

| (a) Compatibility of laws or standards with effective management |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) reported that:

- “Australia is a signatory to a number of international agreements and conventions (which it applied within its EEZ). These include: United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (regulation of ocean space); Convention on Biological Diversity and Agenda 21 (sustainable development and ecosystem based fisheries management); Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES; protection of threatened, endangered and protected species); Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (standards of behaviour for responsible practices regarding sustainable development); United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement; and State Member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (marine protected areas).

- The Offshore Constitutional Settlement provides for the Australian Commonwealth to manage fisheries beyond 3 nautical miles from the coast, or inside 3 miles if so delegated (e.g. the Northern Prawn Fishery). The fishery is managed by the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) in accordance with the Fisheries Management Act (FMA) of 1991 and Fisheries Management Regulations 1992, the Fisheries Administration Act 1991 and the Fisheries (Administration) Regulations 1992.

- Commonwealth-managed fisheries are also subject to aspects of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000.”

Accordingly, there is an effective national legal system to deliver on the outcomes expressed in Components 1 and 2.

| (b) Respect for Rights |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) report that “Special provision for ‘traditional fishing’ is made where they might apply in the contexts of both Commonwealth and State Fisheries Law. A system or mechanism to formally commit to the legal rights created explicit or established by custom on people dependent on fishing for food (non-commercial use) is enshrined in the Native Title Act”. This allows for special provision for ‘traditional fishing’ is made where they might apply in the contexts of both Commonwealth and State Fisheries Law.

The Northern Prawn fishery is a specialist offshore commercial fishery. Indigenous rights are however considered in the context of The Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT) s 12(1) which empowers the Administrator to close the seas adjoining and within 2km of Aboriginal land, to others who are not Aborigines entitled by tradition to enter and use the seas in accordance with that tradition. Before doing so they may (and in case of dispute he must) refer a proposed sea closure to the Aboriginal Land Commissioner. These issues are taken into account through NORMAC consultation processes and in the context of closed areas discussions. Once seas are closed it is an offence for a person to enter or remain on these seas without a permit issued by the relevant Land Council. Therefore, the management system formally commits to the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom of people”.

Given the above, the management system has a mechanism to observe the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom of people dependent on fishing for food or livelihood.

CRITERIA: (ii) The management system has effective consultation processes that are open to interested and affected parties. The roles and responsibilities of organisations and individuals who are involved in the management process are clear and understood by all relevant parties.

| (a) Roles and Responsibilities |

LOW RISK |

|

The roles and responsibilities of the main people (e.g. Fisheries Minister, AFMA Commissioners) and organisations (AFMA) involved in the Australian Commonwealth fisheries management process are well-understood, with relationships and key powers explicitly defined in legislation (e.g. FMA, FAA) or relevant policy statements (e.g. AFMA Fisheries Management Paper 1 – Management Advisory Committees). MRAG Americas (2018) report that “AFMA undertakes the day to day management of the Commonwealth fisheries under powers outlined in the FMA and Fisheries Administration Act 1991. Overarching policy direction is set by the Australian Government through the relevant Minister responsible for fisheries, acting upon advice from the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Roles and responsibilities are divided between the respective management organisation (AFMA), the Northern Prawn Industry Pty Ltd (http://npfindustry.com.au), the Northern Prawn Management Advisory Committee (NORMAC) (http://www.afma.gov.au/fisheries/committees/northern-prawn-management-advisorycommittee/) and NPRAG (http://www.afma.gov.au/fisheries/committees/northern-prawnresource-assessment-group/). As part of AFMA’s partnership approach to fisheries management, it has established NORMAC, which is AFMA’s main point of contact with client groups in the NPF and plays an important role in helping AFMA to fulfil its legislative functions and pursue its objectives (Smith et al., 1999). The MAC comprises representatives of the NPF industry, environmental organisations, research interests and fishery managers. Permanent observers are also appointed, which may include the Department of Environment, Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics (ABARES), and representatives of CSIRO. The role of the NORMAC is clearly defined (AFMA 2003, AFMA 2015a, AFMA 2011, AFMA 2015b). NORMAC provides advice to AFMA on a variety of issues, including the harvest strategy and other on-going measures required to manage the fishery, including the development of management plans, research priorities and projects for the fishery. The functions, roles and responsibilities are explicitly defined and well understood for all areas of responsibility and interaction.”

| (b) Consultation Process |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) report that:

- “AFMA provides opportunities for public comment on fisheries management plans and holds around half of AFMA’s Commission meetings in regional centres providing opportunities for direct access to AFMA Commissioners by stakeholders and the general public. NORMAC considers the wide range of information including local knowledge as part of its advisory processes. The minutes of NORMAC meeting are publicly available (AFMA, 2016d). These include rationale on how local knowledge has, or has not, been incorporated into management advice to the AFMA Commission. The AFMA Commission (and Parliament), may reject NORMAC advice. In respect to the AFMA Commission, NORMAC will always receive a letter from the Commission outlining any decisions made on NORMAC recommendations, including explanations as to acceptance or rejecting of NORMAC recommendations.”

- “The development of the demarcated closed and protected areas includes direct consultation with indigenous interests and ongoing awareness on traditional rights (Jarrett & Barwick, 2010).”

- “Evidence shows that the consultation processes regularly seek and accept relevant information, including local knowledge. The management system demonstrates consideration of the information and explains how it is used or not used.”

These arrangements meet the low risk SG.

CRITERIA: (iii) The management policy has clear long-term objectives to guide decision making that are consistent with Components 1 and 2, and incorporates the precautionary approach.

| (a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) note that “The long-term objectives of the management system are specified in the FMA and the EPBC Act, and further defined in the Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy and Guidelines. The objectives and policy guidance are consistent with MSC’s Principles and Criteria and explicitly require application of the precautionary principle. The fishery is also subject to the Commonwealth EPBC Act which requires periodic assessment against the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries. These Guidelines are consistent with the MSC Principles and Criteria and encourage practical application of the ecosystem approach to fisheries management.” These arrangements are consistent with the low risk SG.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

3B: Fishery Specific Management System

CRITERIA: (i) The fishery specific management system has clear, specific objectives designed to achieve the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2.

| (a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) note that

- The Northern Prawn Fishery Management Plan 1995 reinforces the objectives of the FMA as the objectives of the Plan. Fishery specific objectives for each sub fishery can be identified in the Northern Prawn Fishery Harvest Strategy (Dichmont et al., 2014), and these are reviewed on a regular basis (the previous strategy set out in 2011). The Strategy contains references to use of measurable indicators such as target and limit reference points”;

- “The Bycatch Management Strategy (MRAG, 2012) applies to each subfishery and has historically relied on the use of Environmental Risk Assessments to assess the potential impact of the fishery, and underlined by a series of technological gear mitigation measures, as well as spatial and temporal approaches. For the Tiger prawn fishery, these measures achieved more than a 50% reduction of bycatch since 1998. The revised Bycatch Action Plan specifies the outcomes. A separate NPFI Bycatch Management Strategy (NPFI, 2015) seeks to achieve a 30% reduction. P2 outcomes include a reduction on small fish and sea snake bycatch, strengthening data, the application of effective bycatch reduction devices, addressing ETP interactions.”

- “The operationalization of these strategies is supported by an NPF Industry Code of Practice for Responsible Fishing (AFMA, 2004), formerly Northern Prawn Fishing Industry Organisation and a Northern Prawn Fishery Operational Information Booklet (AFMA, 2016a), and the Bycatch and Discarding Workplan (AFMA, 2014-2016).”

These arrangements are consistent with the low risk SG.

CRITERIA: (ii) The fishery specific management system includes effective decision making processes that result in measures and strategies to achieve the objectives and has an appropriate approach to actual disputes in the fishery.

| (a) Decision making |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) note that:

- “The decision-making processes by AFMA is based on advice from NORMAC (working with NPF RAG and the NPF Research and Environment Committee (NPF REC)) (AFMA, 2015). The workings of these groups include evaluation and assessment of each sub fishery and are transparent with feedback provided by the Commission directly from NORMAC and to stakeholders through media such as the regular AFMA Update and through the Annual public meeting of both the MAC and AFMA. The decision-making process for the NPF is consistent with those for the broader management system and responds to the defined harvest and bycatch management strategies, which respond to research, outcomes evaluations and monitoring programmes. The AFMA website contains an extensive list of evaluations, research reports and assessments, and evidence exists within the NORMAC and the NPFRAG that decisions respond to these findings (http://www.afma.gov.au/fisheries/northern-prawn-fishery/)..”

“The decision making process for the NPF is consistent with those for the broader commonwealth management system and responds to the defined harvest and bycatch management strategies, which respond to research, outcome evaluations and monitoring programmes. Specific and relevant issues are evaluated through the MAC and NPFRAG and mechanisms are in place that take account of the wider implications of decisions.”

| (b) Use of the Precautionary Approach | LOW RISK |

MRAG Americas (2018) conclude that “The harvest strategies and control rules applied to each sub fishery incorporate a precautionary approach to the decision-making process by requiring a review when the target reference level is not met. This ensures that any warning signs are recognised and investigated / addressed in their early stages. The frequency of evaluation (both annually and in-season) and review means that management action to investigate and, where required, alleviate adverse impacts on stocks is always taken before the performance indicators reach the limit reference level.

The application of the research, monitoring and evaluation within the NPF Management Plan, Harvest Strategy and Bycatch Management Strategy provides a good tool to assess the relative risks to target species, bycatch, ETP species and habitats in each sub fishery, initiating when appropriate, actions to deal with at risk species and assemblages. Examples of precautionary actions include controlling the trawl footprint, regulating fishing to take account of real time variations in prawn size, temporal and spatial closures; and the voluntary code.”

| (c) Accountability and Transparency |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) reported that:

- “AFMA, CSIRO and the NPF Pty Ltd provide a comprehensive range of reports which confirm fishery performance and how management has responded to findings from recommendations emerging from research, monitoring, evaluation and review activity. (http://www.afma.gov.au/fisheries/northern-prawn-fishery/ and http://npfindustry.com.au/publications/).”

- “Explanations are provided for actions or lack of actions by the organisations tasked with implementation. Failure to achieve the management reference levels is discussed at NORMAC and advice provided to AFMA. AFMA provide responses through the MAC how information is reviewed and the management decisions made (See Northern Prawn Management Advisory Committee past meetings (http://www.afma.gov.au/fisheries/committees/northern-prawn-management-advisorycommittee/normac-past-meetings/)).”

These arrangements are consistent with the low risk SG.

CRITERIA: (iii) Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms ensure the management measures in the fishery are enforced and complied with.

| (a) MCS Implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

The NPF scored 100 for the compliance and enforcement PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “AFMA deploys a comprehensive enforcement system, including at sea patrols and boardings, pre-inspection checks and inspections on offloading (AFMA (2016-2017)). The effectiveness of the inspection system is underlined by a system of risk assessment (AFMA 2015c), where systematic offenders are likely to be singled out. Specific non-compliance areas have been prioritised, notably failure to have a Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) system operating at all times, closure monitoring, effective application of BRDs and TEDs and reporting ETP interactions (AFMA (2016-2017).”

| (b) Sanctions and Compliance |

LOW RISK |

|

A framework of sanctions for non-compliance is set out in the FMA, Maritime Powers Act 2013 and Fisheries Management Regulations 1992. These include powers to issue warnings, cautions, directions, Observer Compliance Notices, Commonwealth Fisheries Infringement Notices (CFINs), amend fishing concession conditions, suspend or cancel fishing concessions and prosecute offenders through the courts (AFMA, 2015a). Evidence exists that fishers comply with the management system including providing information of importance to the effective management of the fishery. Across all years between 2011-12 and 2015-16, no action was required in >90% of boat inspections in Commonwealth fisheries (total inspections 879) (AFMA, 2015b).

MRAG Americas (2018) noted that “AFMA operates an effective compliance system, but focuses primarily of awareness raising prior to the start of the fishing seasons in each sub fishery. When infringements are detected the penalty process implemented equates to the seriousness of offence, culminating in a sequence of warnings, expedited offences and prosecutions, leading to license confiscation for serious offences. The main tool applied is AFMA Commonwealth Fisheries Infringement Notices (CFINs), which are on the spot fines.

The schedule of fines is based on a penalty unit system defined in Section 95 of the FMA, 1991, with fines offences specified on the Fisheries Management regulations (1992) with defined Index to offences. The combination of substantial enforcement and the small number of offences taking place is evidence that sanctions are a demonstrably effective deterrent. Company enforcement action adds another level of deterrent.”

MRAG Americas (2012) noted that “AFMA acts on intelligence provided and there is a considerable degree of peer pressure applied within the industry to ensure compliance. This is also cemented by the NPF Code of Conduct which ensures the application of best practice such as reporting ETP interactions, and applying appropriate handling practices.” Overall, they concluded that “sanctions to deal with non-compliance exist, are consistently applied and demonstrably provide effective deterrence”.

CRITERIA: (iv) There is a system for monitoring and evaluating the performance of the fishery specific management system against its objectives.

There is effective and timely review of the fishery specific management system.

| (a) Evaluation coverage |

LOW RISK |

|

MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “The Australia Government commissioned two independent reviews of the core Acts (EPBC Act and FMA) governing the environment and fisheries (Hawke, 2009, and Borthwick, 2012). The Borthwick review also included reviews of policy settings, recasting AFMA’s objectives, fisheries management plans, the Minister’s powers to vary fisheries management plans, integrating fisheries and environmental assessments, Research, fisheries management and industry levies, Offshore Constitutional Settlements (OCS), Recreational Fishing, Aquaculture, Compliance and enforcement and Co-management. The Government response to the Borthwick Review was announced in March 2013. DAFF thereafter initiated a public consultation process DAFF (2012/2013), followed by specific Reports on Harvest Strategy and Bycatch management strategy (DAFF 2013a, DAFF 2013b). Thereafter, this prompted NPF to revise their fishery specific harvest (Dichmont et al., 2014), and bycatch management strategies (NPFI, 2015).”

Overall, they concluded that “the fishery has in place mechanisms to evaluate all parts of the management system”.

| (b) Internal and/or external review |

LOW RISK |

|

The NPF scored 100 for the monitoring and management performance evaluation PI in its 2018 MSC re-assessment. MRAG Americas (2018) reported that “AFMA’s management system is subject to internal and external performance evaluation including:

Internal peer reviews, which include:

- The requirement to report in AFMA’s Annual Report on overall performance against the legislative objectives, statutory requirements and financial reporting, the effectiveness of internal controls and adequacy of systems; and the Authority’s risk management processes;

- AFMA and the MAC to periodically assess the effectiveness of the management measures taken to achieve the objectives of this Management Plan by reference to the performance criteria specified in the Plan

- An AFMA MAC/RAG Workshop focusing on managing conflicts of interest, the Productivity Commission review of commercial fisheries management, the regulatory outlook etc.

- AFMA and NORMAC developing performance measures and responses to avoid overcapitalisation and encourage autonomous structural adjustment in the NPF

- NPF research proposals reviewed by the AFMA Research Committee and those for FRDC funding by the Commonwealth Research Advisory Committee

- The NPF harvest strategy remains consistent with the Australian government’s Harvest Strategy Policy

- Review of AFMA’s ERA-ERM Framework – new Guidelines for fisheries have been drafted and will be finalised by 30 June 2017; and

- AFMA also has an internal quality assurance program to determine whether Compliance best practice has been followed

External reviews, which include:

- Questioning by the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport in Senate Estimates hearings (three times/year);

- Annual reporting of NPF performance against protected species and export approval requirements under the EPBC Act consistent with the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries (See below);

- The Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) annual status reports (last published late 2016) on the ecological and economic sustainability of fisheries managed by AFMA;

- US biennial review and accreditation of fishing gear to meet Turtle Excluder Device requirements;

- The draft Productivity Commission review of commercial fisheries regulation in Australia which has made a number of draft recommendations relevant to AFMA (the final report is due to be completed shortly);

- The Australian National Audit Office periodic reviews of aspects of AFMA’s performance. This includes an audit of AFMA’s risk management procedures which is currently underway.

These reviews constitute a review on NPF’s fishery-specific management system including its subfisheries.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

Acknowledgements

This seafood risk assessment procedure was originally developed for Coles Supermarkets Australia by MRAG Asia Pacific. FRDC is grateful for Coles’ permission to use its Responsibly Sourced Seafood Framework.

It uses elements from the GSSI benchmarked MSC Fishery Standard version 2.0, but is neither a duplicate of it nor a substitute for it. The methodology used to apply the framework differs substantially from an MSC Certification. Consequently, any claim about the rating of the fishery based on this assessment should not make any reference to the MSC.