Commonwealth Southern Squid Jig Fishery

Assessment Summary

|

Commonwealth Southern Squid Jig Fishery |

Unit/s of Assessment: |

|

|

Product Name/s: |

Gould’s Squid |

|

|

Species: |

Gould’s Squid (23 636004), )Nototodarus gouldi |

|

|

Southern Australia |

||

|

Gear type: |

Jig |

|

|

Year of Assessment: |

2017 |

|

Fishery Overview

The following summary of the fishery is adapted from Hansen and Bath (2016):

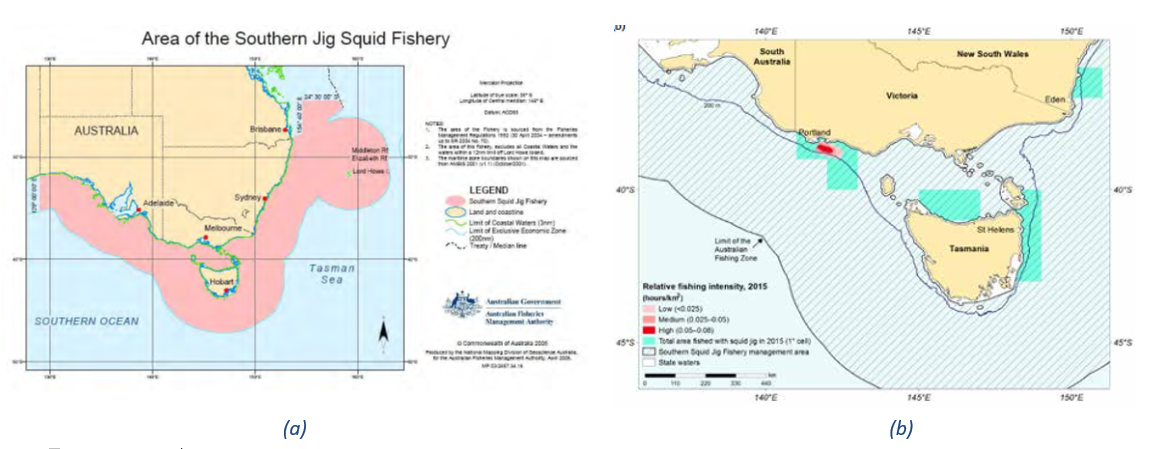

The Southern Squid Jig Fishery (SSJF) is located off New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and in a small area off southern Queensland (Figure 1a). Most fishing takes place off Portland, Victoria (Figure 1b). Australian jig vessels typically operate at night in continental-shelf waters between depths of 60 and 120 m. Squid are also caught in the Commonwealth Trawl Sector (CTS) and the Great Australian Bight Trawl Sector (GABTS). In recent years, more squid has been landed by these sectors than by the SSJF.

The SSJF is a single-method (jigging), single-species fishery, targeting Gould’s Squid (Nototodarus gouldi). Up to 10 automatic jig machines are used on each vessel; each machine has two spools of heavy line, with 20 to 25 jigs attached to each line. High-powered lamps are used to attract squid. Squid in the CTS and GABTS are caught by demersal trawling.

The Commonwealth SSJF is managed by the Australian Government, whereas jigging operations within coastal waters (inside the 3 nautical mile limit) are managed by the relevant state government.

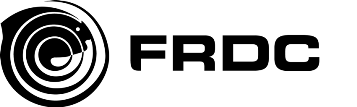

In 2015, there were 5 500 gear statutory fishing rights (SFRs) and seven active vessels, and fishing effort was 1 304 jig hours. Despite brief increases in effort in 2011 and 2012, annual jig fishing effort has been below the long-term average since 2006. High costs relative to revenue, combined with the highly variable nature of the stock, are the main reasons for the reduction in effort since 2008. Effort increased in 2015 as a result of increased market prices and improved access to domestic markets.

Figure 1: (a) Area of the Australian Southern Squid Jig Fishery (Source: AFMA) and (b) relative fishing intensity in 2015 (Source: Hansen and Bath, 2016).

|

Performance Indicator |

Gould’s Squid |

|

COMPONENT 1 |

LOW RISK |

|

1A: Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

LOW RISK |

|

COMPONENT 2 |

LOW RISK |

|

2A: Other Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2B: ETP Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2C: Habitats |

LOW RISK |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

LOW RISK |

|

COMPONENT 3 |

LOW RISK |

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW RISK |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

LOW RISK |

- No formal stock assessment exists for this stock. Gould’s Squid is short lived (less than 1 year) and its biological characteristics mean the population can rapidly increase in biomass during favourable environmental conditions.

- Effort in the fishery is very low in the context of historical levels of fishing effort.

- Squid jig gear is highly targeted and interactions with non-target species are very limited. All impacts of the fishery on target species, bycatch species, ETP species, habitats and communities assessed under a Level 1 ecological risk assessment were rated low or negligible.

|

Component |

Outlook |

Comments |

|

Target fish stock |

Stable |

Fishing effort is currently low in the context of historical effort levels, influenced by economic conditions. |

|

Environmental impact of fishing |

Stable |

Squid jig gear is relatively benign, with few non-target species interactions. No major changes are expected to Component 2 scoring. |

|

Stable |

No major changes are expected to Component 3 arrangements. |

This report sets out the results of an assessment against a seafood risk assessment procedure, originally developed for Coles Supermarkets Australia by MRAG Asia Pacific. The aim of the procedure is to allow for the rapid screening of uncertified source fisheries to identify major sustainability problems, and to assist seafood buyers in procuring seafood from fisheries that are relatively well-managed and have lower relative risk to the aquatic environment. While it is based on elements from the GSSI benchmarked MSC Standard version 2.0, the framework is not a duplicate of it nor a substitute for it. The methodology used to apply the framework differs substantially from an MSC Certification. Consequently, any claim made about the rating of the fishery based on this assessment should not make any reference to the MSC or any other third party scheme.

This report is a “live” document that will be reviewed and updated on an annual basis.

Detailed methodology for the risk assessment procedure is found in MRAG AP (2015). The following provides a brief summary of the method as it relates to the information provided in this report.

Assessments are undertaken according to a ‘unit of assessment’ (UoA). The UoA is a combination of three main components: (i) the target species and stock; (ii) the gear type used by the fishery; and (iii) the management system under which the UoA operates.

Each UoA is assessed against three components, consistent with the MSC principles:

- Target fish stocks;

- Environmental impact of fishing; and

- Management system.

Each component has a number of performance indicators (PIs). In turn, each PI has associated criteria, scoring issues (SIs) and scoring guideposts (SGs). For each UoA, each PI is assigned one of the following scores, according to how well the fishery performs against the SGs:

- Low risk;

- Medium risk;

- Precautionary high risk; or

- High risk

Scores at the PI level are determined by the aggregate of the SI scores. For example, if there are five SIs in a PI and three of them are scored low risk with two medium risk, the overall PI score is low risk. If three are medium risk and two are low risk, the overall PI score is medium risk. If there are an equal number of low risk and medium risk SI scores, the PI is scored medium risk. If any SI scores precautionary high risk, the PI scores precautionary high risk. If any SI scores high risk, the PI scores high risk.

For this assessment, each component has also been given an overall risk score based on the scores of the PIs. Overall risk scores are either low, medium or high. The overall component risk score is low where the majority of PI risk scores are low. The overall risk score is high where any one PI is scored high risk, or two or more PIs score precautionary high risk. The overall risk score is medium for all other combinations (e.g. equal number of medium/low risk PI scores; majority medium PI scores; one PHR score, others low/medium).

For each UoA, an assessment of the future ‘outlook’ is provided against each component. Assessments are essentially a qualitative judgement of the assessor based on the likely future performance of the fishery against the relevant risk assessment criteria over the short to medium term (0-3 years). Assessments are based on the available information for the UoA and take into account any known management changes.

Outlook scores are provided for information only and do not influence current or future risk scoring.

Table 1: Outlook scoring categories.

|

Outlook score |

Guidance |

|

Improving |

The performance of the UoA is expected to improve against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

|

Stable |

The performance of the UoA is expected to remain generally stable against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

|

Uncertain |

The likely performance of the UoA against the relevant risk assessment criteria is uncertain. |

|

Declining |

The performance of the UoA is expected to decline against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

Information to support scoring is obtained from publicly available sources, unless otherwise specified. Scores will be assigned on the basis of the objective evidence available to the assessor. A brief justification is provided to accompany the score for each PI.

Assessors will gather publicly available information as necessary to complete or update a PI. Information sources may include information gathered from the internet, fishery management agencies, scientific organisations or other sources.

[sta_anchor id=”C1″]COMPONENT 1: Target fish stocks

|

1A: Stock Status |

||

|

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing. |

||

|

(a) Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

|

Genetic studies support the hypothesis of a single biological stock of Gould’s Squid throughout south-eastern Australian waters (Noriega et al, 2016). Noriega et al (2016) report that “no formal stock assessment is available for the Gould’s Squid biological stock in Australia. Gould’s Squid is short lived (less than 1 year), spawns multiple times during its life, and displays highly variable growth rates, and size and age at maturity1. These characteristics mean that the population can rapidly increase in biomass during favourable environmental conditions; it is therefore less susceptible to becoming recruitment overfished than longer-lived species. However, as the fishery targets individuals less than 1 year of age, there is potential for the population to be recruitment overfished if insufficient animals survive long enough to reproduce.” Hansen and Bath (2016) report that:

On the basis of the above, they conclude that the stock is not overfished. Although there is limited empirical evidence estimating a conventional BMSY or proxies, the weight of available evidence suggests the stock is currently being fished at very low levels and probably highly likely to be above the point of recruitment impairment. The fact that overall catch and effort in recent years is substantially lower than in 2001 when a preliminary depletion analysis suggested the stock was not overfished, is a plausible argument to suggest there is no reason why the stock is not capable of producing maximum sustainable yield based on environmental drivers. |

||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place. |

|||

|

(a) Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

||

|

The southern Australia biological stock of N. gouldi is harvested by a range of fisheries including:

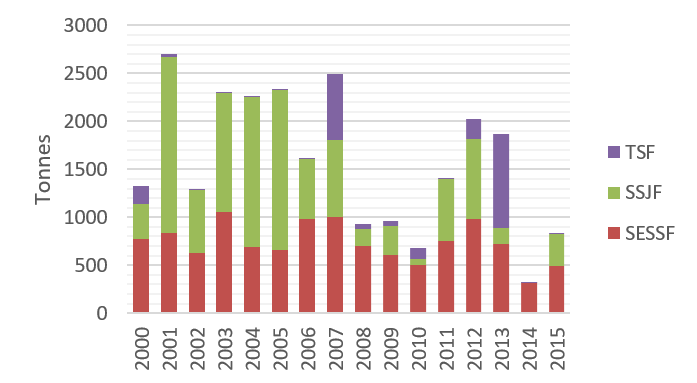

Catches in the two Commonwealth fisheries have historically dominated total landings, however substantial catches were taken in the TSF in 2012-13 (Figure 2). Recreational catches in Tasmania were estimated at 21t in 2012-13 (Noriega et al, 2016).

Figure 2: Australian Gould’s Squid commercial catches between 2000 and 2015. In the SSJF, Statutory Fishing Rights (SFRs) have been issued under the Southern Squid Jig Fishery Management Plan 2005. Once nominated to a boat, these SFRs authorise the holder to use a certain number of squid jigging machines during the year. The number of machines is determined by a Total Allowable Effort (TAE) limit, set annually (Anon, undated). There is no Total Allowable Catch (TAC) or catch quota for the SSJF: a TAC is unable to be determined given the extent of biological data available. Currently there is insufficient scientific information available to set biological reference points for squid, although preliminary biomass estimates from ecosystem models are orders of magnitude higher than catch (Anon, undated). The SESSF is subject to limited entry arrangements, as well as TACC/ITQs on the main commercial species. The SSJF and SESSF are subject to management arrangements specified in the Gould’s Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy. This harvest strategy details processes for monitoring and conducting assessments of the biological and economic conditions of the fishery. The harvest strategy covers the SSJF as well as sectors of the SESSF and other Commonwealth fisheries which may take Gould’s Squid in the Australian Fishing Zone. The Gould’s Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy was implemented on 1 January 2008 (AFMA, 2011). In the absence of biomass estimates, the harvest strategy uses suites of intermediate and limit catch and effort triggers based on recent catch history, with values well below historical high catch levels (Anon, undated). A series of defined actions are associated with each trigger (e.g. re-assess the fishery using depletion analysis if a trigger of 5,000t from the SSJF or 6,000t overall is reached). These do not specify catch reductions (or increases) but are consistent with the existing lightly-exploited nature of the fishery (Anon, undated). Under the current SSJF Management Plan, advice will be provided by a Southern Squid Jig Fishery Resource Advisory Group (SquidRAG) on an appropriate management response, should any of the trigger catch levels be reached. The TSF uses jigs and is subject to limited entry, vessel restrictions (<20m) and spatial and temporal closures. There were 12 active vessels in the TSF in 2015, and the number of automatic squid jigging licenses is limited to 7 in 2016-17 [1]. Notwithstanding larger catches in 2011-12 and 2012-13, catch remains well below historical levels. The harvest strategy in the Commonwealth sectors, which have dominated catches except for 2012-13, is responsive to the state of stock and the elements work together towards achieving the stock management objectives reflected in criterion 1A(i). Catches in the TSF should continue to be monitored in the context of ensuring effective management arrangements across the full range of the stock. |

|||

|

Shark-finning |

|||

|

NA |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place. |

|||

|

(a) HCR Design and application |

Low Risk |

||

|

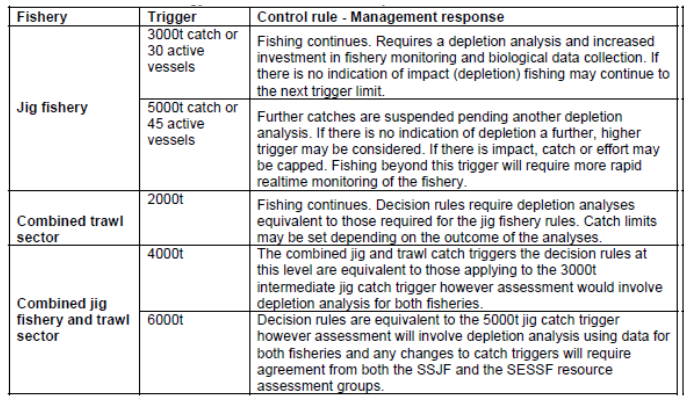

The Commonwealth Gould’s Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy uses a system of within-season monitoring against catch triggers for the jig and trawl sectors that signal the need for formal assessment. The main harvest strategy control rules are outlined in Table 2. Due to relatively low effort in the last few years, these triggers have far exceeded the catch and effort in the fishery. Table 2: Harvest controls for the SSJF (Source: AFMA, 2009).

Although the Commonwealth HCRs do not apply to the TSF, given the historically low levels of catch and the greater potential for fishing effort in the Commonwealth sectors, these rules are likely to ensure that exploitation is reduced as PRI is approached. |

|||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

||

|

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy. |

||||

|

(a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Notwithstanding difficulties in estimating biomass, sufficient information on stock structure, stock productivity and fleet composition are available to support the harvest strategy (see for example Jackson et al, 2003a,b; Virtue et al, 2011; Noriega et al, 2016; Hansen and Bath, 2016, and references therein). |

||||

|

(b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Given the highly variable nature of the stock, the need for abundance monitoring and other assessments (e.g. depletion analysis) is determined by monitoring catch against trigger points in the Gould’s Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy. Where effort and catch remain at low levels, no specific abundance monitoring is required (other than nominal CPUE/catch). In Commonwealth fisheries, removals from the stock are monitored using daily catch and effort logbooks, catch disposal records and occasional observer coverage. AFMA (2009) notes that “due to negligible recorded bycatch, no reported interactions with (ETP) species in the SSJF and no requirement for length/weight data, there has been limited observer coverage in the fishery”. The maximum level of observer coverage between 2005 and 2009 was 2.4%. There has been no observer coverage in 2014 or 2015. Removals from the stock by the TSF are monitored through compulsory catch and effort logbooks. In the Commonwealth sector, monitoring arrangements are consistent with the HCR. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is an adequate assessment of the stock status. |

||||

|

(a) Stock assessment |

MEDIUM RISK |

|||

|

No formal stock assessment exists for this stock (Noriega et al, 2016). AFMA (2009) note that given the high natural variability of arrow squid, the standard stock assessment techniques used for fish such as teleosts or chondrichthyans are not appropriate. Current knowledge of the southern squid resource is insufficient to allow biomass or suitable proxies for reference points to be estimated. Nevertheless, Noriega et al (2016) and Hansen and Bath (2016) use alternative empirical indicators including catch rates and total catch to estimate stock status using a weight of evidence approach. This approach estimates stock status relative to generic reference points appropriate to the species category. |

||||

|

(b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The main uncertainties are taken into account in the weight of evidence approach used by Noriega et al (2016). Although not a formal assessment, their conclusions are subject to external assessment. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

[sta_anchor id=”C2″]COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI. |

||

|

(a) Main other species stock status |

LOW RISK |

|

|

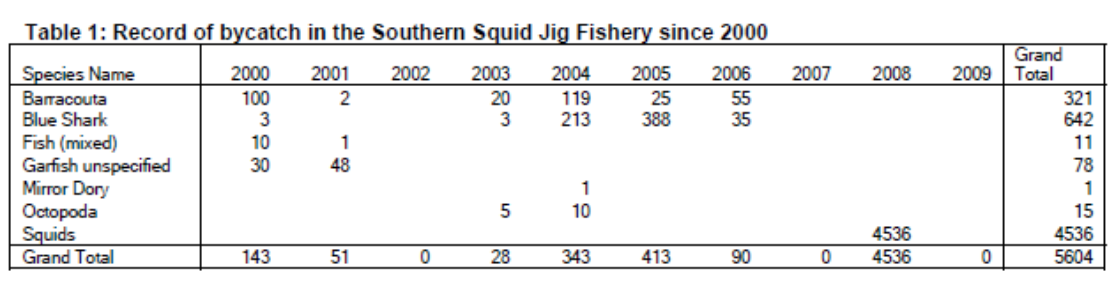

AFMA (2009) reports that “as squid jigging has a very high, target-specific catch rate, there have been negligible levels of bycatch documented to date in the SSJF (Table 2). Since 2001 AFMA logbook records have reported only small quantities of Blue Shark, Garfish (Hemiramphidae – undifferentiated) and Barracouta being taken. These species constitute less than 1 per cent of the total catch for the fishery.” Accordingly, no species qualifies as a main other species. Table 3: Bycatch recorded in the SSJF from 2000 – 2009 (Source: AFMA, 2009)

Hansen and Bath (2016) report that “the SSJF is a highly selective fishery with little bycatch. Occasionally, schools of pelagic sharks, especially Blue Shark (Prionace glauca), are attracted by the schooling squid, and Barracouta (Thyrsites atun) frequently attack squid jigs. However, the main effect of these interactions is damage to, or loss of, fishing gear, and these species are avoided, with operators usually moving to another area when such interactions occur. Some gear is lost at times; it sinks to the seabed as a result of line weights.” Four bycatch and four byproduct species were assessed under a Level 1 (SICA – Scale Intensity Consequence Analysis) ecological risk assessment of the SSJF. All species received risk scores of 1 or 2 (out of 5), with no species requiring assessment under higher ERA levels (Furlani et al, 2007). Accordingly, we have scored this SI low risk. |

||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species; and the UoA regularly reviews and implements |

||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

|

The main measure in place to limit bycatch is the use of highly target specific squid jig gear. Management measures have been developed to avoid and/or reduce the capture and mortality of bycatch species in the SSJF including a Bycatch and Discard Workplan (AFMA, 2009). There are no TAPs, recovery plans, domestic or international agreements in place. Given the very low catch of non-target species, these measures constitute at least a partial strategy to ensure the fishery does not hinder rebuilding of other species. |

||

|

LOW RISK |

||

|

Information reported in fisher logbooks, verified through occasional observer coverage, demonstrating highly target specific catches provides an objective basis for confidence that the strategy is working. |

||

|

(c) Shark-finning |

||

|

NA |

||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Information on the nature and amount of other species taken is adequate to determine the risk posed by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage other species. |

||

|

(a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|

|

Quantitative information through fisher logbooks, as well as occasional observer coverage, has been sufficient to allow the impacts of the fishery on byproduct and bycatch species to be assessed through a Level 1 ERA (Furlani et al, 2007). Increased risk from the fishery can be detected from routine monitoring arrangements including daily catch and effort logbooks, catch disposal records and occasional observer coverage. |

||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species. |

||||

|

(a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The SSJF is not known to interact with any ETP species (AFMA, 2009), and ETP species were scored negligble or low risk in the Level 1 ERA (Furlani et al, 2007). No interactions were reported for the squid jig fishery in 2015 (Hansen and Bath, 2016). Australian Fur Seals commonly forage for squid near operating jig vessels. Research in 2004 investigated the potential for harmful interactions between Australian Fur Seals and squid-jigging operations and found that there was no evidence of jigging operations having a negative impact on seals (Arnould et al. 2003). |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

Also, the UoA regularly reviews and implements measures, as appropriate, to minimise the mortality of ETP species |

||||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

An Ecological Risk Management report for the SSJF was completed in April 2009 and submitted to the Department of Environment Water Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) (AFMA, 2009). The report showed that the risk of jigging to the 216 protected (ETP) species identified as occurring within the area of this fishery was considered negligible or minor (Furlani et al, 2007). Management measures have been developed to avoid and/or reduce the capture and mortality of bycatch species in the SSJF including a Bycatch and Discard Workplan (AFMA, 2009). There are no TAPs, recovery plans, domestic or international agreements in place. |

||||

|

(b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Information from fisher logbooks, occasional observer coverage (Hansen and Bath, 2016) and the outcomes of the Level 1 ERA (Furlani et al, 2007) provides an objective basis for confidence that the strategy will work. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

|

||||

|

(a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Quantitative information through fisher logbooks, as well as occasional observer coverage, has been sufficient to allow the impacts of the fishery on ETP species to be assessed through a Level 1 ERA (Furlani et al, 2007). Increased risk from the fishery can be detected from routine monitoring arrangements including daily catch and effort logbooks, catch disposal records and occasional observer coverage. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to habitat structure and function, considered on the basis of the area(s) covered by the governance body(s) responsible for fisheries management |

||||||

|

(a) Habitat status |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Squid jigging is a pelagic gear type and has no interaction with benthic habitats. Assessment of the Southern Squid Jig Fishery (SSJF) at Level 1 (SICA – Scale Intensity Consequence Analysis) resulted in no habitats or communities requiring assessment at Level 2 (PSA – Productivity Sustainability Analysis) (Furlani et al, 2007). |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the habitats. |

||||||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

An Ecological Risk Management Report has been prepared for the fishery (AFMA, 2009), albeit in practice no partial strategy to limit habitat impacts is necessary. |

||||||

|

(b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The results of the Level 1 ERA (Furlani et al, 2007) provide an objective basis for confidence that the UoA will not impact habitats to the point of serious or irreversible harm. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Information is adequate to determine the risk posed to the habitat by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage impacts on the habitat. |

||||||

|

(a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Given the pelagic nature of the gear type, the nature and distribution of the main habitats are known at a scale and level of detail relevant to the fishery. |

||||||

|

(b) Information and monitoring adequacy |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Information on the nature of squid jigging, as well as logbook information on fishing effort and distribution is sufficient to detect increased risk. |

||||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to the key elements of ecosystem structure and function. |

|||||

|

(i)(a) Ecosystem Status |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

AFMA (2009) report that “there are minimal impacts on the ecosystem by the SSJF as has been confirmed by the Ecological Risk Assessment (2006), the Bycatch Action Plan (2004), the Bycatch and Discarding Workplan (2009) and the draft Ecological Risk Management report (2009)”. Assessment of the Southern Squid Jig Fishery (SSJF) through a Level 1 ERA resulted in no species (target, byproduct, bycatch or protected (ETP)) components, habitats or communities requiring assessment at Level 2 (PSA – Productivity Sustainability Analysis) (Furlani et al, 2007). In addition, Virtue et al (2011) used two ecosystem-based models to investigate the ecological impact of increased fishing pressure on arrow squid in the Great Australian Bight and in south east Tasmania. They report that “model results show that both ecosystems were fairly robust to high levels of fishing on arrow squid populations. We found that the current fishing effort on arrow squid would need to be increased substantially (i.e. by a factor of at least x500 in the GAB system) before noticeable changes occur to their populations. Increased fishing levels would however cause a direct positive effect on principal prey groups (mainly sardines and myctophids) and negative effects on predators (New Zealand fur seals and predatory fish). Cascading effects of arrow squid removal include those from a changing demographic structure and increased feeding competition on important lower-trophic groups such as zooplankton”. Given the highly variable nature of the squid stock, very low levels of fishing effort and minimal impacts on non-target species, ETP species and habitats, it appears at least highly likely that the SSJF is not likely to disrupt the key elements underlying ecosystem structure and function to the point of serious or irreversible harm. |

|||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There are measures in place to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem structure and function. |

|||||

|

(a) Management Strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

The management measures in place which serve to limit ecosystem impacts are largely those detailed in the harvest strategy for target species (limited entry, TACs/ITQs, gear restrictions) and other/ETP species (non-target species reporting, observer monitoring,). In addition, a formal harvest control rule for TAC setting has been developed and will be commenced if effort in the fishery increases sufficiently. An Ecological Risk Management Report has also been prepared for the fishery (AFMA, 2009). These measures are constitute at least a partial strategy. |

|||||

|

(b) Management Strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

The results of the Level 1 ERA (Furlani et al, 2007) provide an objective basis for confidence that the strategy will work, and compliance and observer information provides evidence that the strategy is being implemented. |

|||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) There is adequate knowledge of the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem. |

|||||

|

(a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

Information available on the key elements of the ecosystem in the area of the SSJF (target species, byproduct, ETP species, habitats, communities) has been sufficient to examine the risk from the fishery through the Level 1 ERA (Furlani et al, 2007). Routine monitoring programs in place through AFMA (daily catch and effort logbooks, catch disposal records, occasional observer coverage) are likely to be sufficient to detect increased risk. |

|||||

|

(b) Investigations of UoA impacts |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

Given the very limited impacts on byproduct species, ETP species and habitats, the main impacts of the SSJF on the ecosystem is likely to come from the removal of the target species. The main impacts from the fishery can be inferred from existing information (e.g. catch and effort records, observer records, Level 1 ERA) and the ecosystem level impacts of fishing within the area of the SSJF have been investigated in detail using Ecopath and Atlantis ecosystem models (Virtue et al, 2011). |

|||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

||||

[sta_anchor id=”C3″]COMPONENT 3: Effective management

|

CRITERIA: (i) The management system exists within an appropriate and effective legal and/or customary framework which ensures that it:

|

||||

|

(a) Compatibility of laws or standards with effective management |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Relevant Australian Commonwealth Acts, subsidiary legislation and cooperative instruments, including the EPBC Act 1999, Fisheries Management Act (FMA), Fisheries Administration Act (FAA), and Offshore Constitutional Settlement (OCS) agreements with relevant Australian States, provide an effective legal framework for the purposes of delivering management outcomes consistent with Components 1 and 2. The FMA takes account of the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement and FAO’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. |

||||

|

(b) Respect for Rights |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The management system has a mechanism to formally commit to the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom on people dependent on fishing for food and livelihood. The Commonwealth Native Title Act 1993 formally commits to the rights of indigenous people who can demonstrate their customary rights to fish in a particular area. This legislation provides a mechanism for the making of binding decisions about native title rights to areas of land and water and thereby ensures access to fish resources for people who depend on fishing for their food. AFMA’s jurisdiction typically begins three nautical miles offshore, thus, there is usually no overlap between Commonwealth commercial fishing and customary fishing activity. However, for some fisheries, consideration of customary fishing is largely made through interaction between AFMA’s management and the Native Title Act 1993. Where AFMA modifies an act, a direction or other legislative instrument in a way that may affect native title, that change triggers the ‘future act’ provision of the Native Title Act 1993. In situations where a future act provision could possibly be triggered, AFMA provides the opportunity for relevant native title bodies to be consulted and provide comment. In addition, Fisheries Legislation Amendment (Representation) Bill 2017 is currently before the Commonwealth parliament. The Bill provides for explicit recognition of recreational and Indigenous fishers in Commonwealth legislation and requires AFMA to have regard to ensuring that the interests of all fisheries users are taken into account in Commonwealth fisheries management decisions[2]. Given the above, the management system has a mechanism to observe the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom of people dependent on fishing for food or livelihood. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The management system has effective consultation processes that are open to interested and affected parties. The roles and responsibilities of organisations and individuals who are involved in the management process are clear and understood by all relevant parties. |

||||

|

(a) Roles and Responsibilities |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The roles and responsibilities of the main people (e.g. Fisheries Minister, AFMA Commissioners) and organisations (AFMA) involved in the Australian Commonwealth fisheries management process are well-understood, with relationships and key powers explicitly defined in legislation (e.g. FMA, FAA) or relevant policy statements (e.g. AFMA Fisheries Management Paper 1 – Management Advisory Committees). There is a Management Advisory Committee (South East Management Advisory Committee – SEMAC) and Resource Assessment Group (SquidRAG) relating to the SSJF. |

||||

|

(b) Consultation Process |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Consultation in the SSJF occurs either directly with license holders on operational issues affecting the fishery, or through the SEMAC. The committee includes representatives from AFMA, scientific agencies, environmental non-government organisations, the recreational/charter fishing sector and state governments. The committee holds four to five meetings each year to discuss sustainable catch limits and strategic management issues. Summaries of MAC meetings are made available on AFMA’s website. SEMAC is supported by the Southern Squid Jig Fishery Resource Assessment Group (SquidRAG). The main role of the SquidRAG is to provide advice on the status of the squid stock, the impact of squid fishing on the marine environment and strategic research priorities. This group also uses the Southern Squid Jig Fishery Harvest Strategy to provide annual recommended total allowable effort limits for squid catches in the upcoming Southern Squid Jig Fishery season. This recommended effort limit is provided as advice to the SEMAC and the AFMA Commission. These arrangements meet the low risk SG. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) The management policy has clear long-term objectives to guide decision making that are consistent with Components 1 and 2, and incorporates the precautionary approach. |

||||

|

(a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The long term objectives of the management system are specified in the FMA and the EPBC Act, and further defined in the Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy and Guidelines. The objectives and policy guidance are consistent with Components 1 and 2 and explicitly require application of the precautionary principle. The fishery is also subject to the Commonwealth EPBC Act which requires periodic assessment against the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries. These Guidelines are consistent with the MSC Principles and Performance Indicator and encourage practical application of the ecosystem approach to fisheries management. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

3B: Fishery Specific Management System |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The fishery specific management system has clear, specific objectives designed to achieve the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2. |

||||||

|

(a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Fishery specific objectives for the SSJF, consistent with Components 1 and 2, are explicitly set out in the Southern Squid Jig Fishery Management Plan 2005. These are consistent with Australia’s obligations under international agreements, national legislation and specifically require application of the precautionary principle. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The fishery specific management system includes effective decision making processes that result in measures and strategies to achieve the objectives and has an appropriate approach to actual disputes in the fishery. |

||||||

|

(a) Decision making |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Australia’s Commonwealth fisheries decision making process is well established and set out explicitly in relevant legislation (e.g. FMA, FAA) and policy documents (e.g. Looking to the Future, Commonwealth Harvest Strategy Policy). Given the very low levels of recent effort, recent examples of changes within the SSJF management system to meet management objectives (other than TAC declarations) are rare, however sufficient evidence exists from other Commonwealth fisheries that the decision making process is capable of achieving fishery-specific objectives (e.g. annual adjustment of TACs to meet harvest strategy targets, ceasing overfishing in accordance with the Ministerial Direction issued to AFMA in 2005 and in accordance with the HSP). |

||||||

|

(b) Use of the Precautionary approach |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The precautionary approach is explicitly required in both the FMA and the SSJF Management Plan. Given the very low levels of effort in the fishery over recent years and the absence of any high risk interactions detected through ERA, specific examples in which precautionary approaches are required in the SSJF are rare in recent years. Nevertheless, the preparation of a formal harvest strategy and the precautionary scoring of interactions through the ERA process could be viewed as examples of a precautionary approach. |

||||||

|

(c) Accountability and Transparency |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Information on the biological, ecological, economic and social performance of the fishery is tracked and reported the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) Fishery Status Reports, ABARES Fishery Surveys, National Fish Stock Status reporting and through the AFMA website. Relevant information on recent changes to management and new scientific or monitoring results are also discussed with stakeholder representatives through the SEMAC process. Feedback on actions taken or not taken by AFMA is provided to SEMAC. These measures are consistent with the low risk SG. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms ensure the management measures in the fishery are enforced and complied with. |

||||||

|

(a) MCS Implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

AFMA’s framework for its National (Domestic) Compliance and Enforcement Program is set out in the AFMA National Compliance Operations and Enforcement Policy (AFMA, 2015a). The policy is compliant with the Australian Fisheries National Compliance Strategy 2010-15 and aims to “effectively deter illegal fishing in Commonwealth fisheries and the Australian Fishing Zone”. Compliance activities are informed by risk assessments undertaken in accordance with the international standard for risk management (ISO 31000:2009) across all major Commonwealth domestic fisheries (AFMA, 2015a). Compliance operations are supported through a centralised structure with separate Intelligence, Planning and Operations units. More specific annual compliance priorities and risk treatments are set out in AFMA’s National Compliance and Enforcement Program 2016 -17 (AFMA, 2015b). Key priorities for 2016-17 include (i) failure to have a Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) or Electronic Monitoring (e-monitoring) system operating at all times, (ii) quota evasion and (iii) bycatch mishandling, which has been identified as an emerging risk. Risks are treated through a program of general deterrence (i.e. inspections and patrols designed to target identified high risk ports, boats and fish receivers), and other targeted measures – e.g. physical and technical surveillance, standard investigative activity, intelligence gathering, and media strategies. Compliance Risk Management Teams (CRMTs) may be formed to help address priority risks (e.g. VMS/electronic monitoring offences; quota evasion). These measures constitute a system which has demonstrated an ability to enforce management measures. |

||||||

|

(b) Sanctions and Compliance |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

A framework of sanctions for non-compliance is set out in the FMA, Maritime Powers Act 2013 and Fisheries Management Regulations 1992. These include powers to issue warnings, cautions, directions, Observer Compliance Notices, Commonwealth Fisheries Infringement Notices (CFINs), amend fishing concession conditions, suspend or cancel fishing concessions and prosecute offenders through the courts (AFMA, 2015a). Some evidence exists that fishers comply with the management system including providing information of importance to the effective management of the fishery. Across all years between 2011-12 and 2015-16, no action was required in >90% of boat inspections in Commonwealth fisheries (total inspections 879) (AFMA, 2015b). |

||||||

|

LOW RISK |

||||||

|

No systematic non-compliance is thought to exist. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iv) There is a system for monitoring and evaluating the performance of the fishery specific management system against its objectives. |

||||||

|

(a) Evaluation coverage |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The framework of performance indicators against which measures taken in the Management Plan are assessed is set out in Section 7 of the plan. These include both procedural and outcome-based performance indicator. The evaluation of the management system is carried out through the SEMAC process. |

||||||

|

(b) Internal and/or external review |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The fishery-specific management system is subject to regular internal review through the SEMAC process, which tracks performance of the fishery against the objectives in the Management Plan. AFMA is also required to report in its Annual Report on overall performance against the legislative objectives, statutory requirements and financial reporting, the effectiveness of internal controls and adequacy of the Authority’s risk management processes. The fishery is subject to regular external assessment through the ongoing assessment for export approval under the EPBC Act against the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries. Moreover, ABARES reports on the ecological and economic sustainability of fisheries managed by AFMA and the Australian National Audit Office undertakes periodic reviews of aspects of AFMA’s performance (e.g. ANAO, 2013). |

||||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||||

AFMA (2009). Ecological Risk Management Report for the Southern Squid Jig Fishery. (Accessed at: http://www.afma.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/SSJF_ERM_Apr09.pdf)

AFMA (2011). Southern Squid Jig Fishery. Management Arrangements Booklet Season 2011.

AFMA (2015a). National Compliance and Enforcement Policy 2015. 31pp.

AFMA (2015b). National Compliance and Enforcement Program 2016 -17. 45pp.

Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) (2013). Administration of the Domestic Fishing Compliance Program. 128pp.

Arnould, J., Trinder, D.M. and McKinley, C.P. (2003), Interactions between fur seals and a squid jig fishery in southern Australia, Marine and Freshwater Research, vol. 54, no. 8, pp. 979-984.

Furlani, D., S. Ling, A. Hobday, J. Dowdney, C. Bulman, M. Sporcic, M. Fuller. (2007) Ecological Risk Assessment for the Effects of Fishing: Southern Squid Jig Sub-fishery. Report for the Australian Fisheries Management Authority, Canberra. 151pp.

Hansen, S. and Bath, A. (2016). Southern Squid Jig Fishery. in Patterson, H, Noriega, R, Georgeson, L, Stobutzki, I & Curtotti, R 2016, Fishery status reports 2016, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra. CC BY 3.0.

Jackson, GD & McGrath-Steer, BL (2003a), Gould’s Squid in southern Australian waters—supplying management needs through biological investigations, final report to the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, project 1999/112, Institute of Antarctic and Southern Ocean Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart.

Jackson GD, McGrath-Steer B, Wotherspoon S, Hobday AJ (2003b) Variation in age, growth and maturity in the Australian arrow squid Nototodarus gouldi over time and space: what is the pattern? Marine Ecology Progress Series 264: 57-71.

MRAG Asia Pacific (2015). Coles Future Friendly Sourcing Assessment Framework. 12pp.

Noriega, R., Lyle, J., Hall, K and Emery, T. (2016). Gould’s Squid Nototodarus gouldi. in Carolyn Stewardson, James Andrews, Crispian Ashby, Malcolm Haddon, Klaas Hartmann, Patrick Hone, Peter Horvat, Stephen Mayfield, Anthony Roelofs, Keith Sainsbury, Thor Saunders, John Stewart, Ilona Stobutzki and Brent Wise (eds) 2016, Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2016, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

Virtue, P, Green, C, Pethybridge, H, Moltschaniwskyj, N, Wotherspoon, S & Jackson, G (2011), Gould’s Squid: stock variability, fishing techniques, trophic linkages—facing the challenges, final report to the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, project 2006/12, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, Hobart.

[1] http://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/sea-fishing-aquaculture/commercial-fishing/scalefish-fishery/commercial-scalefish

[2] http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/bd1617a/17bd090

Summary of main issues