Coral Trout – Queensland Coral Reef Fin Fish Fishery

Assessment Summary

Coral Trout

Unit of Assessment

Product Name: Coral Trout

Species: Plectropomus spp.; Variola spp.; Plectropomus leopardus

Stock: Queensland east coast

Fishery: Queeensland Coral Reef Fin Fish Fishery

Gear type: Line

Year of Assessment: 2017

Fishery Overview

The Coral Reef Fin Fish Fishery (CRFFF) is a predominantly line-only fishery that targets a range of bottom-dwelling reef fish. It consists of a commercial sector, focusing primarily on Coral Trout and Redthroat Emperor, and important recreational and charter sectors. The fishery operates predominantly in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) with commercial operators generally using smaller tender boats (dories) from a mother vessel.

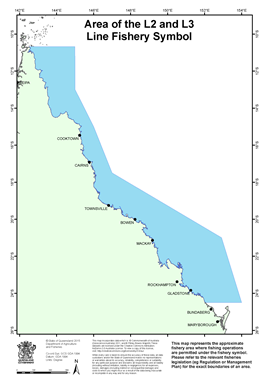

Figure 1: Area of Queensland Coral Reef Fin Fish Fishery (CRFFF)

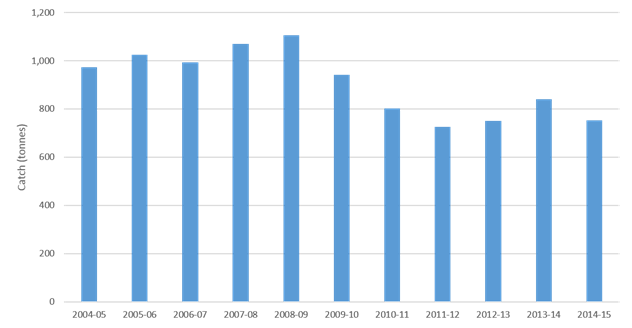

Commercial line fishing occurred in the GBRMPA area long before the establishment of the marine park in 1975. In the period 1988 and 1994 there were between 361 and 416 commercial licences active in the fishery, fishing between 16,000-18,500 fishing days and harvesting between 2,873 and 3,725 tonnes of coral reef fish. Effort grew after 1994, in line with the development of the export market for live Coral Trout. Effort peaked in 2001 with over 700 operators fishing around 40,000 fishing days and harvesting approximately 4,400 tonnes of fish (Mapstone et al, 2004). In 2004, significant changes to the management of the fishery and the GBRMP were introduced including total allowable commercial catches on Coral Trout, Redthroat Emperor and ‘other species’, individual transferable quotas, re-zoning of the GBRMP to create more no take zones and a re-structuring of the commercial sector (Simpfendorfer et al. 2008). Catch and effort has decreased substantially since the introduction of the management plan.

Figure 2: Total commercial catch of Coral Trout in the CRFFF, 2006 – 2015. (Source: Roberts et al, 2016)

Commercial operators with an RQ fishery symbol and who possess a line fishing endorsement in the form of an east coast ‘L’ fishery symbol (i.e. L1, L2, L3) are permitted to take coral reef fin fish (RQ species, see Schedule Five of Fisheries Regulation 2008) in east coast Queensland waters. The line symbol they are operating under dictates the area in which they can fish. Commercial and recreational fishers (including recreational fishers on licensed charter vessels) are permitted to use up to three lines, with no more than six hooks (total), using either a rod and reel or a handline.

“Coral Trout” is managed as a stock complex comprising seven species:

- Barcheek Coral Trout (Plectropomus maculatus)

- Bluespotted Coral Trout (Plectropomus laevis)

- Common Coral Trout (Plectropomus leopardus)

- Yellowedge Coronation trout (Variola louti)

- Vermicular Coral Trout (Plectropomus oligacanthus)

- White-edge Coronation trout (Variola albimarginata)

- Passionfruit Coral Trout (passionfruit trout) (Plectropomus areolatus)

The Common Coral Trout, P. leopardus accounts for the majority of the catch (e.g. Leigh et al, 2014), though no specific estimates of catch composition were found.

Risk Scores

|

Performance Indicator |

Risk Score |

|

LOW RISK |

|

|

1A: Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

LOW RISK |

|

C2 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF FISHING |

LOW RISK |

|

2A: Other Species |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

2B: ETP Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2C: Habitats |

LOW RISK |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

LOW RISK |

|

C3 MANAGEMENT |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW RISK |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

Summary of main issues

- Coral Trout is managed as a stock complex of seven species, with the Common Coral Trout, leopardus, accounting for the majority of the catch. Information on P. leopardus is good, although information on stock abundance of other species is assumed only;

- Recent information on discards in limited, although information is good historically;

- There is conflicting information on the level of compliance with closed areas in the GBRMP. Annual status reports suggest high levels of compliance, although anecdotal evidence indicates potentially high rates of fishing in ‘no take’ zones.

Outlook

Saddletail Snapper – Trawl, Trap/Line

| Component | Outlook | Comments |

| Target fish species | Stable | Catches remain well below estimates of MSY and commercial TAC continues to be adjusted to meet a target reference point well above BMSY. |

| Environmental impact of fishing | Improving | Additional monitoring of other species targeted by the QCRFFF expected under the Monitoring and Research Plan under the Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027. Updated ERA also expected to be undertaken. |

| Management system | Improving | Vessel monitoring systems (VMS) will be required on all commercial line boats by 2018 which will assist in monitoring compliance with spatial closures. |

COMPONENT 1: Target species

1A: Stock Status

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing.

| (a) Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

The most recent assessment of Common Coral Trout estimated that the biomass in 2012 was 60 per cent of the unfished (1962) levels in areas open to fishing (Leigh et al, 2014). Maximum sustainable yield (MSY) was estimated to be around 2010 tonnes per year. The current commercial total allowable catch (TAC) is set at 963t[1], with recreational catch in the offshore component of the fishery estimated at around 105t in 2013 (Roberts et al, 2016). Other species managed in the ‘Coral Trout’ complex have similar biological characteristics to P. leopardus, and have similar Productivity-Susceptibility Analysis (PSA) productivity scores (Annex 1), except for P. laevis, which matures at a larger size and grows to a larger size. These differences are recognised in the management arrangements for the fishery, which establishes a larger minimum legal size for P. laevis (50cm Vs 38cm) and a maximum size (80cm). Given P. leopardus accounts for the majority of the harvest and other species either have similar biological characteristics or are specifically managed in the case of P. laevis, it is reasonable to assume the stock complex is highly likely to be above the point of recruitment impairment (PRI) and likely to be at or above a level consistent with MSY.

[1] https:// https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/LEGISLTN/CURRENT/F/FisherCRFFQD15.pdf

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

1B: Harvest Strategy

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place.

| (a) Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

|

The main elements of the harvest strategy for CRFFF species include:

- limited entry in the commercial fishery;

- commercial TACs for Coral Trout, Redthroat Emperor and a ‘basket’ quota for all other species allocated through individual transferable quotas (ITQs);

- minimum fish size limits that apply to all sectors;

- a maximum size limit for laevis;

- boat size and tender restrictions in the commercial fishery, and gear restrictions for all fishers;

- recreational in-possession limits;

- a combined recreational in-possession limit of 20 coral reef fin fish;

- two annual five-day spawning closures;

- monitoring through commercial catch and effort logbooks, and periodic recreational fishing surveys;

- periodic quantitative assessments of some species (e.g. Coral Trout, RTE) and ongoing monitoring of stock status indicators for selected species.

The fishery is also subject to restrictions on areas in which it can operate through zoning declared under GBRMP and Queensland Marine Parks Zoning Plan limits on operational areas.

Together with the harvest control rule (HCR) described below, the measures for Coral Trout constitute a harvest strategy which is designed to maintain the target stocks at or above MSY. Decision rules for the setting of Coral Trout commercial TAC have been developed which aim to maintain the stock at around B68% (well above BMSY, estimated at ~B20%), and quota reductions were enacted during 2014 for the first time according to these rules. Commercial TAC decisions are informed by periodic quantitative stock assessments, and ongoing monitoring of commercial CPUE. Accordingly, all of the elements of the harvest strategy appear to work together to achieve the stock management objectives reflected in criterion 1A(i) and there is evidence that the harvest strategy is responsive to the state of the stock.

Given the multi-sector nature of the fishery, the main weakness in the existing harvest strategy is the absence of measures linking recreational harvest to the state of the stock – i.e. the HCR covers commercial quotas only. Given the substantial catches by the recreational sector (estimated at around 105t in 2013; Roberts et al, 2016) and the absence of overall catch limits, this is a source of uncertainty in achieving stock management objectives.

| Redthroat Emperor |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The existing measures for Redthroat Emperor are expected to achieve the stock management objectives reflected in criterion 1A(i). The commercial TAC of 700t is set well below the estimated MSY level (760–964t), and actual commercial catches have been well below the TAC since 2004-05 (Roberts and Fairclough, 2016). In 2015-16, only 26% (159t) of the commercial TAC was harvested. Recreational catch is small in comparison to the commercial catch, and combined commercial + recreational catches remain well below estimated MSY levels. Accordingly, the current arrangements meet the medium risk SG. Nevertheless, there is limited evidence that the harvest strategy is responsive to the state of the stock. The commercial TAC has not been changed since its introduction in 2004, no stock specific harvest controls rules exist and the stock assessment has not been updated since 2006. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

| (b) Shark-finning |

|

|

NA

CRITERIA: (ii) There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place.

(a) HCR Design and application

| Coral Trout |

LOW RISK |

|

Well-defined HCRs have been agreed for the commercial component of the fishery (DAFF, 2014). These decision rules aim to maintain stock size at around B68, well above MSY, for economic reasons. The decision rules ensure that the exploitation rate is reduced as PRI is reached through pre-agreed reductions in commercial TAC. The main weakness is the absence of equivalent measures on the recreational sector.

| Redthroat Emperor |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

There are currently no well-defined HCRs in place for Redthroat Emperor, although tools are in place through the commercial TAC and recreational bag limits to reduce exploitation if required. A Performance Measurement System (PMS) (DEEDI, 2011) was developed to monitor the effectiveness of management measures against operational objectives, including those for Redthroat Emperor, although assessments against most elements of the PMS have been discontinued (DAF, 2015). The extent to which performance measures for Redthroat Emperor have been actively monitored in recent years is not clear from publicly available information.

The medium risk SG for this scoring issue requires that “generally understood HCRs and tools are in place or available that are expected to reduce the exploitation rate as the point of recruitment impairment (PRI) is approached”. The MSC Certification Requirements v2 (GSA2.5.2 – 2.5.5) specifies that “the expectation is that ‘available’ HCRs may meet the SG60 level in cases where stock biomass has not previously been reduced below the BMSY level or has been above it for a sufficiently long recent time, and it is ‘expected’ that the management authority will introduce HCRs for this species in the future if needed”. It also notes that “that this could reasonably be ‘expected’ for the target species in cases where HCRs are currently being ‘effectively’ used by the same management agency on at least one other species of similar importance (i.e. of a similar average catch levels and value)”. For Redthroat Emperor both of these conditions appear to be met. The stock was most recently assessed as being well above BMSY (Leigh et al, 2006), and since that time combined commercial and recreational catches have been well below the estimated MSY level. Moreover, the management agency has effectively used HCRs in other similar fisheries (e.g. Coral Trout, Spanner Crabs), and has recently announced a package of management reforms including a commitment to develop harvest strategies with formal HCRs for all major fisheries by the end of 2020 (DAF, 2017). Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK – Coral Trout

1C: Information and Assessment

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy.

| (a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|

Numerous studies of the biology of the Coral Trout have been conducted over the past two decades (e.g. Mapstone et al., 2004; Bergenius et al, 2005; 2006; Heupel et al, 2010; Frisch et al, 2016). The biological stock structure of Coral Trout species is spatially complex and remains uncertain (e.g. Leigh et al, 2014); hence, status is typically reported at the management unit level rather than for individual biological stocks. Nevertheless, information is sufficient to support the harvest strategy. Good information is available on the fleet structure of the commercial and charter sectors. Sufficient information is available on the fleet structure and catches in the recreational sector to periodically estimate catch (e.g. Webley et al, 2015).

| (b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

LOW RISK |

|

Stock abundance and removals from the UoA are monitored through commercial and charter logbooks, commercial quota catch documentation and periodic stock assessments (e.g. Leigh et al, 2014). Recreational catch is monitored periodically (every 3-5 years; e.g. Webley et al, 2015). Standardised commercial CPUE is monitored annually consistent with the requirements of the HCR. There are likely to be limited removals from the stock, other than from the commercial, recreational and charter sectors. Accordingly, this SI is scored low risk. CRITERIA: (ii) There is an adequate assessment of the stock status.

| (a) Stock assessment |

LOW RISK |

|

Leigh et al (2014) assessed the status of Common coral trout (Plectropomus leopardus), which makes up the bulk of the ‘Coral Trout’ catch using a regional, age-structured, forward-prediction population dynamic model. It was written in the software AD Model Builder (ADMB) (Fournier et al., 2012) and built on the general-purpose stock assessment model Cabezon (specifically, the Original Cabezon or OC model) (Cope et al., 2003). The assessment model has been tuned for regional circumstances (e.g. green zone fishing) and is capable of estimating population size relative to reference points. Notwithstanding conflicts between some data sets (e.g. underwater visual census data vs commercial catch rates), the assessment was appropriate for the stock and estimated status relative to reference points that are appropriate the to the stock and can be estimated.

| (b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The assessment attempts to account for numerous sources of uncertainty, although the publicly available information does not confirm whether it has been peer-reviewed.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK – Coral Trout

COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

2A: Other Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA(s) aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI.

| (a) Main other species stock status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The intent of this scoring issue is to examine the impact of the units of assessments on ‘main’ other species taken while harvesting the target species. ‘Main’ is defined as any species which comprises >5% of the total catch (retained species + discards) by weight in the UoAs, or >2% if it is a ‘less resilient’ species. The aim is to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired and ensure that, for species below the PRI, there are effective measures in place to ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery and rebuilding.

The QCRFFF focuses on Coral Trout and Redthroat Emperor as the main target species, but also harvests a large number of other species including tropical snappers (e.g. Saddletail Snapper, Stripey Snapper, Red Emperor), emperors (e.g. Spangled Emperor) and cods/groupers (e.g. Coral Cods, Cephalopholis spp.). Apart from the two target species, no other species has accounted for >5% of the retained catch across the 2013-14 to 2015-16 period on average. Redthroat Emperor is assessed under Component 1 in the full assessment report. Saddletail Snapper (Lutjanus malabaricus) accounted for the next highest percentage at around 3.5% of the total retained catch. Spangled Emperor (Lethrinus nebulosus), Red Emperor (Lutjanus sebae) and Stripey Snapper (Lutjanus carponotatus) accounted for 3.1%, 2.3% and 2.2% respectively.

Limited information is available on discards in the fishery in recent years, although comprehensive information was generated through the Effects of Line Fishing on the Great Barrier Reef (ELF) experiment in the late 1990s (Mapstone et al, 2004). Discards were dominated by undersized individuals of the main target species, with Coral Trout and Redthroat Emperor accounting for 61% and 56% of discards amongst fishing operations focused on ‘dead’ fish and ‘live’ fish respectively (DPI&F, 2005).

Although no species other than Coral Trout (43.1%) and Redthroat Emperor (10.4%) accounted for >5% of the retained catch, and species accounting for between 2% and 5% of the catch do not meet the criteria as ‘less resilient’, we have assessed Saddletail Snapper, Spangled Emperor, Red Emperor and Stripey Snapper here for the sake of conservatism.

Saddletail Snapper

Genetic studies indicate that the Saddletail Snapper comprises three biological stocks: the North Coast Bioregion biological stock, the Northern Australian biological stock (including the Timor Sea, Arafura Sea and the Gulf of Carpentaria) and the East coast of Queensland biological stock (Salini et al, 2006). Martin et al (2016) conclude that although the available information is insufficient to confidently classify the status of this stock, current levels of combined commercial and recreational pressure are unlikely to result in the stock becoming recruitment overfished.

Spangled Emperor

The east coast stock of Spangled Emperor was most recently assessed as undefined[1]. Assessors noted that although no species-specific monitoring occurs for this species, commercial catches had been stable since 2008-09 and the minimum legal size would protect a large proportion of females and males from harvesting. Assessors also noted that the stock would receive some protection from marine reserves in the GBRMP and there are no sustainability concerns for the stock.

Red Emperor

Stock delineation has not occurred for Red Emperor off the east coast of Queensland and status is usually presented at the management unit level. Newman et al (2016) classified the stock as undefined given the absence of stock assessments and other information to confidently classify the status of the stock. Commercial catch has reduced from 100-200t per year during the period 1997–98 to 2004–05 to 20-60t since 2004-05, following the introduction of the commercial quota system and the rezoning of the GBRMP. A minimum legal size of 55cm applies to this species and the stock would also receive some protection from marine reserves in the GBRMP.

Stripey Snapper

The Stripey Snapper stock off Queensland’s east coast has most recently been assessed as sustainable[1]. Assessors noted that commercial catch and effort trends have remained stable since 2004-05 and the minimum legal size is set above size at maturity, meaning undersized fish have the opportunity to breed at least once. Assessors also noted that it is likely a significant portion of the overall biomass is protected within marine parks, the species is highly fecund and current level of fishing pressure is unlikely to cause the stock to become recruitment overfished.

Accordingly, while there is uncertainty around the status of some other species taken in the fishery, measures appear to be in place that are expected to ensure that the UoAs do not hinder recovery and rebuilding of the main non-target species if necessary. This is consistent with medium risk. The UoAs do not meet low risk because there is neither evidence that the other species assessed here are highly likely to be above the PRI or that there is a demonstrably effective strategy in place to ensure the UoAs do not hinder recivery and rebuilding if necessary.

[1] https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/fisheries/monitoring-our-fisheries/commercial-fisheries/data-reports/sustainability-reporting/stock-status-assessments/stock-status-assessment-2015/stripey-snapper

[1] https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/fisheries/monitoring-our-fisheries/commercial-fisheries/data-reports/sustainability-reporting/stock-status-assessments/stock-status-assessment-2015/spangled-emperor

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species; and the UoA regularly reviews and implements

| (a) Management strategy in place |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The main management measures in place limiting fishing mortality on species are similar to those for the target species and include:

- limited entry in the commercial fishery;

- a ‘basket’ quota for ‘other species’ allocated through individual transferable quotas (ITQs);

- minimum fish size limits;

- boat size and tender restrictions in the commercial fishery, and gear restrictions;

- two annual five-day spawning closures;

- monitoring through commercial catch and effort logbooks; and

- spatial closures under GBRMP and Queensland Marine Parks Zoning Plans.

Weight of evidence based stock assessments of some species (e.g. Saddletail Snapper, Crimson Snapper, Red Emperor, Stripey Snapper, Hussar) are undertaken periodically[1]. Although no species is classified as ‘overfished’, several remain ‘undefined’.

Key weaknesses in the information base to assess the effectiveness of management arrangements include a lack of species specific reporting for some groups and an absence of mechanisms to independently validate commercial catch and effort reporting. While a performance measure to examine trends in bycatch through observer information was included in the PMS (DEEDI, 2011), the fishery has had no observer coverage in recent years.

An Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA) was conducted on the ‘other species’ component of the QCRFFF in 2007 (DPI&F, 2007).

The UoA has measures in place (particularly through minimum legal sizes, spatial closures, monitoring through commercial logbooks and periodic weight of evidence based assessments) that could be expected to maintain other species assessed here at levels likely to be above the PRI. Nevertheless, given the absence of any species specific monitoring or objectives for these species the current measures are unlikely to be considered a partial strategy. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk.

[1] https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/fisheries/monitoring-our-fisheries/commercial-fisheries/data-reports/sustainability-reporting/stock-status-assessments/summary-2016; https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/fisheries/monitoring-our-fisheries/commercial-fisheries/data-reports/sustainability-reporting/stock-status-assessments/stock-status-assessment-2015

| (b) Management strategy evaluation |

MEDIUM RISK |

There are no quantitative stock assessments for any of the other species assessed, although evidence presented in weight of evidence based stock status assessments provide a plausible argument that the measures should work (e.g. the minimum legal size allows for spawning at least once, marine reserves protect a proportion of the population).

| (c) Shark-finning |

NA

CRITERIA: (iii) Information on the nature and amount of other species taken is adequate to determine the risk posed by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage other species.

| (a) Information |

MEDIUM RISK |

The main quantitative information on non-target species comes from compulsory commercial catch and effort logbooks, as well as targeted research studies (e.g. Mapstone et al, 2004; Little et al, 2007). Recent information on discards is limited, although historical information is more comprehensive (e.g. Mapstone et al, 2004; DPI&F, 2005; Brown et al, 2008; Welch et al, 2008). Measures to independently validate commercial catch and effort information in recent years have been limited. Relatively good basic biological knowledge exists for many species. The available information is adequate to broadly estimate the impact of the UoA on other species assessed here, and is adequate to support measures to manage other species.

PI SCORE – MEDIUM RISK

2B: Endangered Threatened and/or Protected (ETP) Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species.

The UoAs does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

LOW RISK |

|

A number of endangered, threatened and protected (ETP) species occur within the area fished by the CRFFF including sea turtles, marine mammals, marine birds and sharks. Interactions with protected species in the commercial sector of the CRFFF are primarily monitored through a Species of Conservation Interest (SOCI) logbook which has been in place since 2002. Only two interactions with ETP were reported between 2002-2010 (DEEDI, 2011), although we have found no updates since then. DPI&F (2005) report that few interactions have been reported in independent monitoring programs (e.g. DAF LTMP, CRC Reef ELF Project), while a preliminary analysis of the likelihood of ETP species interacting with the QCRFFF suggested the possibility of interaction was remote or rare in most cases. DEE (2017) concluded that while reporting in SOCI logbooks appears limited, previous consideration of TEP interactions in the fishery indicate risks are low. Although recent specific information is limited, the available evidence suggests it is highly likely that the UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

- meet national and international requirements; and

- ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

The ‘strategy’ in place for minimising the impact of the fishery on ETP species includes:

- gear restrictions which limit operators to actively fished line gear which has a low rate of interaction with ETP species;

- live release of ETP species;

- monitoring of interactions through a mandatory, separate SOCI logbook which has been in place since 2002;

- a system of spatial closures covering >20% of all reef habitat types within the GBRMP.

An indicator within the CRFFF Performance Measurement System (PMS) evaluates whether the percentage of protected species released alive falls below 90%. The extent to which the PMS is still actively monitored is uncertain, although DAF (2015) suggests the SOCI information continues to be assessed. An education program on mitigation of impacts to ETP species was produced in 2005 (DEEDI, 2011). Given the infrequent nature of interactions in the fishery, these measures are likely to be considered at last a partial strategy to ensure the UoAs do not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

The relatively benign nature of the gear type together with information from independent monitoring programs (DAF LTMP, CRC Reef ELF Project; DPI&F, 2005) reporting very few interactions with ETP species provides an objective basis for confidence that the partial strategy will work. More recent reporting through SOCI logbooks provides some evidence that the strategy is being implemented successfully, however there is limited validation of fisher reporting.

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

- information for the development of the management strategy;

- information to assess the effectiveness of the management strategy; and

- information to determine the outcome status of ETP species.

| (a) Information |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Interactions with ETP species is primarily monitored through a mandatory, separate SOCI logbook which has been in place since 2002. Some information on rates of interaction is also available through independent monitoring programs (e.g. DAF LTMP, CRC Reef ELF Project; DPI&F, 2005). Although some quantitative information is available, no formal ERA of the potential impacts of the fishery has been conducted and there are few measures in place to independently validate SOCI logbook reporting. Nevertheless, sufficient qualitative information is available to estimate the UoA related mortality on ETP species, and is adequate to support measures to manage impacts on ETP species.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

2C: Habitats

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to habitat structure and function, considered on the basis of the area(s) covered by the governance body(s) responsible for fisheries management

| (a) Habitat status |

LOW RISK |

|

Examples of “serious or irreversible harm” to habitats include the loss (extinction) of habitat types, depletion of key habitat forming species or associated species to the extent that they meet criteria for high risk of extinction, and significant alteration of habitat cover/mosaic that causes major change in the structure or diversity of the associated species assemblages (MSC, 2014). Further, if a habitat extends beyond the area fished then the full range of the habitat should be considered when evaluating the effects of the fishery. The ‘full range’ of a habitat shall include areas that may be spatially disconnected from the area affected by the fishery and may include both pristine areas and areas affected by other fisheries.

Line fishing is a selective and non-destructive form of fishing gear. None of the many studies conducted on the effects of line fishing on reef habitats have documented impacts that are likely to reduce habitat structure and function to the point of serious or irreversible harm (e.g. Mapstone et al, 2004). While reef habitats can be dynamic, historic impacts in the GBRMP area have been mainly due to other factors such as crown-of-thorn starfish outbreaks and more recent impacts to cyclone damage and global warming (Sweatman et al. 2011, Hughes et al. 2011, Tobin et al. 2011). In addition to the benign nature of the gear, the zoning plan of the GBRMP closes large areas of representative habitat to fishing activities which would serve to mitigate fishing-related impacts to the area as a whole. Accordingly, we have scored this SI low risk.

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the habitats.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

The main ‘strategy’ to limit habitat damage in the fishery is to limit gear to benign hook and line apparatus. The fishery is also subject to substantial spatial closures under the GBRMP Zoning Plan, which closes >20% of each reef and non-reef bioregion identified in the marine park to fishing activities. These measures are likely to be considered at least a partial strategy which is expected to achieve the outcome reflected in criterion 2C(i).

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

The zoning plan and compliance information showing fishers comply with requirements to use line fishing apparatus provide some objective basis for confidence that the strategy will work and that the measures are being implemented.

CRITERIA: (iii) Information is adequate to determine the risk posed to the habitat by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage impacts on the habitat.

| (a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

|

Despite ongoing information gaps, the GBRMP area is one of the most well-studied marine environments in the world. Habitat types were mapped in considerable detail to support the rezoning of the GBRMP in 2004 (e.g. Kerrigan et al, 2010). This mapping exercise was informed by decades of independent scientific research. Accordingly, the nature, distribution and vulnerability of the main habitat types are known at a level of detail relevant to the scale and intensity of the fishery.

| (a) Information and monitoring adequacy |

LOW RISK |

|

The physical impacts of line fishing gear on habitats are expected to be minimal, albeit this may not have been quantified fully due to higher research priorities being placed on other issues. However, existing information is likely to be sufficient to understand the potential impacts and spatial (areal and vertical) overlaps. Sufficient data on habitats are being collected by other GBRMP monitoring programmes which aim to address a broad range of potential impacts to reef environments (e.g. AIMS LTMP). As the effects of line fishing on habitat are expected to be very small compared to other potential sources of impacts (e.g. climate change, cyclones), fishery-related changes to habitats are not monitored by CRFFF itself.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

2D: Ecosystems

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to the key elements of ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Ecosystem Status |

LOW RISK |

|

In this assessment, serious or irreversible harm in the ecosystem context is interpreted in relation to the capacity of the ecosystem to deliver ecosystem services (MSC, 2014). Examples include trophic cascades, severely truncated size composition of the ecological community, gross changes in species diversity of the ecological community, or changes in genetic diversity of species caused by selective fishing.

The information available from studies on community and trophic level impacts from line fishing in the GBRMP is variable. The Effects of Line Fishing on the Great Barrier Reef (ELF) study specifically examined the effects of line fishery on the reef communities of several regions within the GBRMP (Mapstone et al., 2004). The study found that zoning strategies have been effective in protecting sub-populations of the fishery resource from the impacts of harvest and the protection of such refuges (closed areas), with sufficient compliance, has the potential to sustain high biomass of reproductively mature populations of harvested species in spite of an active fishery on the GBR. In addition, the study found that indirect effects of line fishing on non-harvest fish were not conspicuous. Whilst differences existed between open and closed reefs in abundances of the prey of targeted species, the nature of the patterns varied regionally, through time and with species or species group. In some situations, the patterns in abundance suggested that removal of a key predator (Coral Trout) by fishing might have allowed populations of some prey to grow on fished reefs, but the evidence was neither uniform nor convincing.

This is consistent with Williamson et al (2004) who found that while density and biomass of Coral Trout and Stripey Snapper were higher in protected zones of some inshore regions of the GBRMP, density and biomass of non-target species such as wrasses (Labridae), rabbitfish (Siganidae) and butterflyfish (Chaetodontidae) did not differ significantly between protected and fished zones.

The outcomes were also consistent with Elmslie et al (2015) who undertook underwater visual surveys of coral reef fish and benthic communities at several locations within the GBRMP and found no clear or consistent differences in the structure of fish or benthic assemblages, non-target fish density, fish species richness or coral cover between no-take marine reserves and areas open to fishing. Overall, they noted that the QCRFFF targets a narrow suite of predatory fishes and “thus cannot be considered a major threat to biodiversity”.

By contrast, Boaden and Kingsford (2015) found that depletion of top piscivore predators (e.g. Coral Trout, Stripey Snapper) resulted in an increase in prey fish density along a gradient of fishing intensity, and predator fish density was a strong predictor of prey fish density for many species. The study also found changes in the community composition of prey fishes associated with the depletion of top predatory fishes, as well as impacts on algal cover in some areas open to fishing, but did not find unequivocal evidence of trophic cascades influencing habitats (e.g. live coral cover).

A key consideration in the scoring of this indicator is the extent to which any changes are able to be reversed. This includes, but is not limited to, the permanence of changes in the biological diversity of the ecological community and the ecosystem’s capacity to deliver ecosystem services. To that end, a number of studies have documented relatively rapid increases in the density and biomass of targeted species following management interventions in the GBRMP. For example, Williamson et al (2004) documented increases in the density and biomass of Coral Trout by a factor of 4+ between surveys 3-4 years before the introduction of no-take marine reserves and 12-13 years after reserves in inshore reefs in the GBRMP. Moreover, Russ et al (2008) found that densities of Coral Trout were significantly higher in no-take marine reserves than in adjacent fished sites 1.5-2 years after the new Zoning Plan was introduced into the GBRMP in 2004.

Given the weight of evidence from a number of studies suggesting relatively limited community level impacts from line fishing in the GBRMP and the apparent relatively rapid reversibility of fishing impacts, there is a reasonable case to suggest it is highly unlikely that the UoAs will disrupt the key elements underlying ecosystem structure and function to the point of serious or irreversible harm.

CRITERIA: (ii) There are measures in place to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem structure and function.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

The fishery largely operates within the GBRMP which is subject to a comprehensive ecosystem-based zoning plan incorporating large, representative areas of no-take zones across each reef and non-reef bioregion (GBRMPA, 2005). Boaden and Kingsford (2015) found that marine reserves were effective management measures in protecting targeted species and maintaining ecological processes. The harvest strategy also contains several measures expected to serve to reduce impacts to ecological communities including commercial catch quotas and minimum legal sizes to control exploitation of individual species, and restrictions on gear to benign apparatus. These management measures have been in place since 2004 and are informed by considerable independent scientific research (e.g. Mapstone et al, 2004; Kerrigan et al, 2010). Although there is limited monitoring of some ecosystem components (e.g. discards), these measures constitute at least a partial strategy which takes into account the available information and is expected to restrain the impacts of the UoAs on the ecosystem so as to achieve the outcomes reflected in criterion 2D(i).

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

The outcomes of the ELF experiment (Mapstone et al, 2004) and subsequent studies following the introduction of the new GBRMP Zoning Plan in 2004 (e.g. Elmslie et al, 2015) provide some objective basis for confidence that the measures will work.

CRITERIA: (iii) There is adequate knowledge of the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem.

| (a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

|

Given the extensive study of reef fish assemblages within the CRFFF (e.g. Mapstone et al. 2004; Elmslie et al, 2015; Boaden and Kingsford, 2015), the key elements of the ecosystem are broadly understood. Ongoing monitoring of catch and effort through compulsory logbooks, as well as other independent monitoring programs in place in the GBRMP (e.g. AIMS LTMP[1]), are likely to be sufficient to detect increased risk.

[1] http://www.aims.gov.au/docs/research/monitoring/monitoring.html

| (b) Investigations of UoA impacts |

LOW RISK |

|

Notwithstanding the variable nature of the outcomes of some studies, the main interactions of the fishery on key ecosystem components can be inferred from existing information and have been investigated in detail (e.g. Mapstone et al, 2004; Elmslie et al, 2015; Boaden and Kingsford, 2015).

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

COMPONENT 3: Management system

3A: Governance and Policy

CRITERIA: (i) The management system exists within an appropriate and effective legal and/or customary framework which ensures that it:

- Is capable of delivering sustainability in the UoA(s)

- Observes the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom of people dependent on fishing for food or livelihood; and

- Incorporates an appropriate dispute resolution framework.

| (a) Compatibility of laws or standards with effective management |

LOW RISK |

|

The Queensland Government management and legislative framework is consistent with local, national or international laws or standards that are aimed at achieving sustainable fisheries in accordance with Components 1 and 2.

| (b) Respect for Rights |

LOW RISK |

|

The rights of customary fishers are recognised by the s14 exemption in the Fisheries Act that allows for an “Aborigine or Torres Strait Islander” to take fish for “the purpose of satisfying a personal, domestic or non-commercial communal need”. Additional customary rights may be sought under Commonwealth Native Title legislation.

CRITERIA: (ii) The management system has effective consultation processes that are open to interested and affected parties. The roles and responsibilities of organisations and individuals who are involved in the management process are clear and understood by all relevant parties.

| (a) Roles and Responsibilities |

LOW RISK |

|

The roles and responsibilities of the main organisations and individuals involved in the management process are explicitly defined and well understood, despite the complexities associated with fisheries management in the GBRMP. FQ are responsible for day-to-day management of the QCRFF. GBRMPA are responsible for the broader management of the GBRMP, including spatial management decisions. Accountability relationships between the main agencies and their responsible Ministers are clear. Formal processes exist to coordinate activity within and adjacent to the GBRMP between Commonwealth and State governments. Compliance functions are carried out primarily by the QB&FP, although GBRMPA and DERM staff are also authorised officers under the Fisheries Act.

| (b) Consultation Process |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Until very recently, consultation was undertaken on a targeted, ad hoc basis, primarily with key stakeholder representative organisations, with formal processes to seek information from the main affected parties on important regulatory changes (e.g. release of Regulatory Impact Statements [RISs] seeking public comment). In mid-2017, a multi-stakeholder Coral Reef Fin Fish Fishery Working Group (CRFFFWG) was established as part of the Queensland Government’s Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027. The objectives of the CRFFFWG are to:

- review the annual commercial quota for Coral Trout;

- assist with the development of a harvest strategy for the CRFF Fishery by the end of 2018.

- provide advice to Fisheries Queensland on operational issues and management of Queensland’s CRFF Fishery.

The CRFFFWG includes membership from Fisheries Queensland as well as representatives from the commercial and recreational fishing sectors, GBRMPA, the conservation sector and expert scientists.

The key considerations around whether this SI scores low risk is whether the consultation process regularly seek and accept relevant information from all interested parties, including local knowledge, and whether the management system demonstrates consideration of the information obtained. The medium risk criteria require consultation processes that obtain relevant information from the main affected parties, including local knowledge, to inform the management system. While the new consultative structure appears capable of being a mechanism to meet the low risk criteria, the evidence base is limited given the working group has only recently been established. To that end, we have scored this SI medium risk given the management system does include consultation processes which seeks to obtain relevant information from the main affected parties (e.g. through RISs). Should the new consultative structure regularly seek and accept relevant information from all interested parties, including local knowledge, and demonstrates consideration of the information obtained, this SI may score low risk in future assessments.

CRITERIA: (iii) The management policy has clear long-term objectives to guide decision making that are consistent with Components 1 and 2, and incorporates the precautionary approach.

| (a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|

The Fisheries Act 1994 contains clear long term objectives that are consistent with the outcomes expressed by Component 1 and 2 and the precautionary approach. These are explicit and required by legislation.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

3B: Fishery Specific Management System

CRITERIA: (i) The fishery specific management system has clear, specific objectives designed to achieve the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2.

| (a) Objectives |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

High level fishery-specific objectives were previously outlined in the Fisheries (Coral Reef Fin Fish Fishery) Management Plan 2003, although in April 2015 the provisions in the plan were consolidated into the Fisheries Regulation 2008 (the Regulation) (DAF, 2015). The Regulations and Act contain generic, high level objectives consistent with Components 1 and 2 but these are not fishery specific.

More measurable ‘operational’ objectives and performance indicators were included in the Performance Management System (PMS) for the fishery, although this was largely replaced in 2014 for Coral Trout with a five-year quota setting cycle that includes a series of quota setting decision rules (DAF, 2015). Performance indicators had been developed in the PMS for target species, retained (‘byproduct’) species, bycatch species, ecosystem impacts and socio-economics. Some of the operational objectives and performance indicators were not perfectly aligned with Component 1 and 2 (e.g. the ‘bycatch’ objective is to ‘maintain an acceptable bycatch ratio in the commercial fishery’, rather than an explicit statement about maintaining the health of bycatch populations and the avoidance of threats to biological diversity), although others were well aligned (e.g. the ecosystem objective is to ‘minimise the impact of line fishing on reef ecosystems’).

The status of the non-target species elements of the PMS are somewhat uncertain, although DAF (2015) notes that “the core elements of each PMS will be monitored via the stock status assessment process and through the annual SOCI reporting requirements”. It is not clear that specific long term and short term objectives exist for some MSC components (e.g. non-target species; ecosystem) in the absence of the PMS and previous management plan. Accordingly, the fishery can be considered to have implicit, rather than explicit objectives consistent with Components 1 and 2.

CRITERIA: (ii) The fishery specific management system includes effective decision making processes that result in measures and strategies to achieve the objectives and has an appropriate approach to actual disputes in the fishery.

| (a) Decision making |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The Queensland Government Minister responsible for the fisheries portfolio has ultimate responsibility for the management of the fishery, and is empowered to make changes in accordance with powers under the Fisheries Act 1994. The Minister is advised by Fisheries Queensland who, in turn, seek input from stakeholders (now through the newly established CRFFFWG) and technical agencies. Some decisions may be made by the Chief Executive of FQ under a declaration. A recent example of management change in the CRFFF fishery has been the changes in Coral Trout TACC in 2015 in accordance with the quota decision rules.

While some evidence exists that the management system responds to serious issues in a transparent and timely manner (e.g. CT quota changes), it is not clear that the management system responds to all serious and other important issues in relevant research, monitoring and evaluation in a transparent, timely and adaptive manner. Prior to the Coral Trout TAC adjustments in 2014 and 2015, TACs for all quota species groups had remained unchanged since their introduction in 2004 and there is limited evidence for other recent changes in response to research and monitoring.

A revised decision-making framework which aims to improve flexibility and responsiveness has been proposed as part of the Queensland Government’s Sustainable Fisheries Startegy 2017-2027 (DAF, 2017). Effective operation of the framework, together with input from the CRFFFWG, may result in lower risk scores in future assessments.

| (c) Accountability and Transparency |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Some information on the performance of the fishery is available to stakeholders through the DAF website (e.g. stock assessments, ERAs, catch and effort history) and on request. The primary mechanism by which the fishery’s performance has historically been monitored is through the PMS, with results publicly reported through Annual Status Reports (ASR). In recent years, only core elements of the PMS have been monitored through the stock status assessment process and annual SOCI reporting requirements (DAF, 2015), with the most recent ASR produced for the 2011 fishing year (Queensland Government, 2012). Where significant management changes are required, a RIS is released calling for public comment. The RIS provides an explanation of the background to the proposed changes and alternative options considered. Nevertheless, in the absence of any formal consultative structure, it is not clear that explanations have been provided for any actions or lack of action associated with findings and relevant recommendations emerging from research, monitoring evaluation and review activity. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk. We note that the newly established CRFFFWG – and the public Communiques made available through the DAF website following each meeting – provides a mechanism through which explanations may be provided to stakeholders on any action or lack of action around recommendations arising from research and monitoring.

CRITERIA: (iii) Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms ensure the management measures in the fishery are enforced and complied with.

| (a) MCS Implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The MCS system in the fishery primarily comprises commercial logbooks, quota monitoring through the Automated Interactive Voice Response (AIVR) system, at sea and land-based fisheries inspections of all sectors primarily by the QB&FP, occasional aerial surveillance, clear sanctions set out in legislation enforceable through the courts (or administratively depending on the severity of the offence) and promotion of voluntary compliance through education. Priorities for the MCS system are based on formal risk assessments, updated at least every 3-5 years or with major changes in the fishery. The main uncertainty is the extent to which the existing MCS system is capable of enforcing some key measures in the management of the fishery, most notably poaching in no take areas in the GBRMP. The 2014 stock assessment of Common Coral Trout (Leigh et al, 2014) assumed rates of fishing in green zones were around 20% of the adjacent blue (open) areas, based on discussions with industry and managers. This risk should be better addressed through the planned introduction of VMS on all vessels in the fishery, including tenders (DAF, 2017).

| (b) Sanctions and Compliance |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

The Fisheries Act 1994 establishes a framework of sanctions to deal with non-compliance, including both criminal and administrative penalties depending on the nature and severity of the offence. There is conflicting information on the rates of compliance with the management system, particularly with GBRMP green zones. Rates of compliance reported through the ASRs are generally very high (e.g. 91% in the most recent ASR for the 2011 fishing year; Queensland Government, 2012), and information is provided by fishers to support the effective management of the fishery. Nevertheless, Leigh et al (2014) reported that “Commercial fishers believe overwhelmingly that large amounts of fishing take place inside green zones. One fisher put the rate of noncompliance at about 80% of commercial fishers, and thought that between 20% and 50% of the entire commercial catch on the GBR came from green zones.”

Although this information is anecdotal only, sufficient uncertainty exists for this SI to be scored precautionary high risk. The fishery would be better placed against this indicator with stronger evidence of systematic compliance with no-take areas. Again, the planned introduction of VMS on all vessels in the fishery, including tenders (DAF, 2017), should provide better information to assess this risk.

CRITERIA: (iv) There is a system for monitoring and evaluating the performance of the fishery specific management system against its objectives.

There is effective and timely review of the fishery specific management system.

| (a) Evaluation coverage |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

Historically, the performance of the management system has been monitored through the PMS, although evaluations have been infrequent in recent years. DAF (2015) indicates that “the broader applicability and suitability of the PMS is now being reviewed as part of a broader management reform package being implemented by DAF” and that “given these developments, it was determined that Queensland would not monitor and report against the existing fishery PMS in its entirety. Rather, the core elements of each PMS will be monitored via the stock status assessment process and through the annual SOCI reporting requirements”. To that end, there are mechanisms in place to evaluate some parts of the fishery-specific management system although arguably not all key parts.

| (b) Internal and/or external review |

LOW RISK |

|

Performance of some aspects of the management system (e.g. Coral Trout quotas) are subject to annual internal review (DAFF, 2014). The fishery is also periodically assessed externally by the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Energy under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The fishery’s current export approval expires in 2020.

PI SCORE – PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK

Acknowledgements

This seafood risk assessment procedure was originally developed for Coles Supermarkets Australia by MRAG Asia Pacific. FRDC is grateful for Coles’ permission to use its Responsibly Sourced Seafood Framework.

It uses elements from the GSSI benchmarked MSC Fishery Standard version 2.0, but is neither a duplicate of it nor a substitute for it. The methodology used to apply the framework differs substantially from an MSC Certification. Consequently, any claim about the rating of the fishery based on this assessment should not make any reference to the MSC.