Assessment Summary

|

Commonwealth Northern Prawn Fishery |

Unit/s of Assessment: |

|

|

Product Name/s: |

Moreton Bay Bug |

|

|

Species: |

Moreton Bay Bugs (28 821903), Thenus spp. |

|

|

Northern Prawn Fishery |

||

|

Gear type: |

Demersal trawl |

|

|

Year of Assessment: |

2017 |

|

The following summary of the fishery is adapted from Larcombe et al (2016):

The Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF) uses otter trawl gear to target a range of tropical prawn species. Banana Prawn and two species of Tiger Prawn (brown and grooved) account for around 80 per cent of the landed catch. Byproduct species include Endeavour Prawns, scampi (Metanephrops spp.), bugs (Thenus spp.) and saucer scallops (Amusium spp.). In recent years, many vessels have transitioned from using twin gear to mostly using a quad rig comprising four trawl nets.

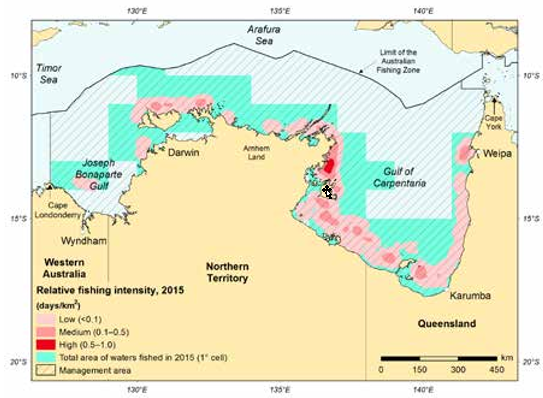

Banana Prawn (Penaeus merguiensis) is mainly caught during the day on the eastern side of the Gulf of Carpentaria, whereas Redleg Banana Prawn (F. indicus) is mainly caught in Joseph Bonaparte Gulf (Figure 1). Tiger Prawns (Penaeus esculentus and P. semisulcatus) are primarily taken at night (daytime trawling has been prohibited in some areas during the Tiger Prawn season). Most catches come from the southern and western Gulf of Carpentaria, and along the Arnhem Land coast. Tiger Prawn fishing grounds may be close to those of Banana Prawns, but the highest catches come from areas near coastal seagrass beds, the nursery habitat for Tiger Prawns. Endeavour Prawns (Metapenaeus endeavouri and M. ensis) are mainly a byproduct, caught when fishing for Tiger Prawns.

Figure 1: Relative fishing intensity in the Northern Prawn Fishery in 2015 (Source: Larcombe et al, 2016).

The NPF developed rapidly in the 1970s, with effort peaking in 1981 at more than 40 000 fishing days and more than 250 vessels. During the next three decades, fishing effort and participation were reduced to the current levels of around 7 500 days of effort and 52 vessels. Total NPF catch in 2015 was 7 825 t, comprising 7 696 t of prawns and 129 t of byproduct species (predominantly bugs, squid and scampi). Annual catches tend to be quite variable from year to year because of natural variability in the Banana Prawn component of the fishery.

Under an Offshore Constitutional Settlement (OCS) agreement between the Commonwealth, Western Australia, Northern Territory and Queensland governments, originally signed in 1988, prawn trawling in the area of the NPF to low water mark, is the responsibility of the Commonwealth through the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA).

The fishery has been certified against the Marine Stewardship Council standard for the main prawn species since 2012[1].

|

Performance Indicator |

Moreton Bay Bug |

|

COMPONENT 1 |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

1A: Stock Status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

COMPONENT 2 |

LOW RISK |

|

2A: Other Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2B: ETP Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2C: Habitats |

LOW RISK |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

LOW RISK |

|

COMPONENT 3 |

LOW RISK |

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW RISK |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

LOW RISK |

- The NPF has been certified against the Marine Stewardship Council’s Fishery Standard for the main target prawn species since 2012.

- Moreton Bay Bugs are taken as a byproduct species in the NPF. No formal assessment of the stock has been undertaken, although quantitative estimates of acceptable biological catch (ABC) have been developed using independent trawl survey data. Catches in the last decade have remained well below the ABC estimate.

- There are currently no well-defined HCRs in place for Moreton Bay Bugs in the NPF, although the stock is subject to a minimum legal size and a precautionary trigger catch limit of 100t which triggers a review of available data to identify any sustainability issues if reached.

- The fishery is well placed against Component 2 and 3 PIs.

Moreton Bay Bugs

|

Component |

Outlook |

Comments |

|

Target fish stocks |

Stable |

Catches have remained well below estimates of acceptable biological catch (ABC) for the past decade. Given Moreton Bay Bugs are taken as a byproduct and catch has remained well below ABC, there is little incentive to undertake formal stock assessments of develop well-defined HCRs. |

|

Environmental impact of fishing |

Stable |

No major changes are expected to Component 2 arrangements. |

|

Stable |

No major changes are expected to Component 3 arrangements. |

This report sets out the results of an assessment against a seafood risk assessment procedure, originally developed for Coles Supermarkets Australia by MRAG Asia Pacific. The aim of the procedure is to allow for the rapid screening of uncertified source fisheries to identify major sustainability problems, and to assist seafood buyers in procuring seafood from fisheries that are relatively well-managed and have lower relative risk to the aquatic environment. While it is based on elements from the GSSI benchmarked MSC Standard version 2.0, the framework is not a duplicate of it nor a substitute for it. The methodology used to apply the framework differs substantially from an MSC Certification. Consequently, any claim made about the rating of the fishery based on this assessment should not make any reference to the MSC or any other third party scheme.

This report is a “live” document that will be reviewed and updated on an annual basis.

Detailed methodology for the risk assessment procedure is found in MRAG AP (2015). The following provides a brief summary of the method as it relates to the information provided in this report.

Assessments are undertaken according to a ‘unit of assessment’ (UoA). The UoA is a combination of three main components: (i) the target species and stock; (ii) the gear type used by the fishery; and (iii) the management system under which the UoA operates.

Each UoA is assessed against three components, consistent with the MSC principles:

- Target fish stocks;

- Environmental impact of fishing; and

- Management system.

Each component has a number of performance indicators (PIs). In turn, each PI has associated criteria, scoring issues (SIs) and scoring guideposts (SGs). For each UoA, each PI is assigned one of the following scores, according to how well the fishery performs against the SGs:

- Low risk;

- Medium risk;

- Precautionary high risk; or

- High risk

Scores at the PI level are determined by the aggregate of the SI scores. For example, if there are five SIs in a PI and three of them are scored low risk with two medium risk, the overall PI score is low risk. If three are medium risk and two are low risk, the overall PI score is medium risk. If there are an equal number of low risk and medium risk SI scores, the PI is scored medium risk. If any SI scores precautionary high risk, the PI scores precautionary high risk. If any SI scores high risk, the PI scores high risk.

For this assessment, each component has also been given an overall risk score based on the scores of the PIs. Overall risk scores are either low, medium or high. The overall component risk score is low where the majority of PI risk scores are low. The overall risk score is high where any one PI is scored high risk, or two or more PIs score precautionary high risk. The overall risk score is medium for all other combinations (e.g. equal number of medium/low risk PI scores; majority medium PI scores; one PHR score, others low/medium).

For each UoA, an assessment of the future ‘outlook’ is provided against each component. Assessments are essentially a qualitative judgement of the assessor based on the likely future performance of the fishery against the relevant risk assessment criteria over the short to medium term (0-3 years). Assessments are based on the available information for the UoA and take into account any known management changes.

Outlook scores are provided for information only and do not influence current or future risk scoring.

Table 1: Outlook scoring categories.

|

Outlook score |

Guidance |

|

Improving |

The performance of the UoA is expected to improve against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

|

Stable |

The performance of the UoA is expected to remain generally stable against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

|

Uncertain |

The likely performance of the UoA against the relevant risk assessment criteria is uncertain. |

|

Declining |

The performance of the UoA is expected to decline against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

Information to support scoring is obtained from publicly available sources, unless otherwise specified. Scores will be assigned on the basis of the objective evidence available to the assessor. A brief justification is provided to accompany the score for each PI.

Assessors will gather publicly available information as necessary to complete or update a PI. Information sources may include information gathered from the internet, fishery management agencies, scientific organisations or other sources.

[sta_anchor id=”C1″]COMPONENT 1: Target fish stocks

|

1A: Stock Status |

||

|

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing. |

||

|

(a) Stock Status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

|

No studies have been carried out on the biological stock structure of Australian Moreton Bay Bugs (Zeller et al, 2016). Given the uncertainty in stock structure, assessment of stock status is presented here at the management unit level. Zeller et al (2016) report that “Northern Prawn Fishery (Commonwealth) trawl surveys were used to estimate the biomass of Moreton Bay Bugs in the Gulf of Carpentaria, from which an estimate of acceptable biological catch was derived. This assessment estimated the annual acceptable biological catch for Moreton Bay Bugs in the fishery at 1887 tonnes (t) (95 per cent confidence interval 1716–2057 t). Annual commercial catches have remained well below this (catch peaked at 120 t in 1998). Catches were 59 t in 2014 and 77 t in 2015.” On the basis of the above, they conclude that the stock is not overfished. Given annual catches remain well below estimates of acceptable biological catch, it is probably highly likely that the stock is above the point of recruitment impairment. However, there is limited evidence to demonstrate that the stock meets the second part of the low risk scoring guideline, namely that the stock is fluctuating at or around BMSY. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk. |

||

|

PI SCORE |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place. |

|||

|

(a) Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

||

|

The harvest strategy for the NPF is structured around the targeted prawn species and is described in detail by MRAG Americas (2012). Fishing mortality is managed through a combination of input controls (limited entry, seasonal closures, permanent area closures, gear restrictions and operational controls), which are implemented under the Northern Prawn Fishery Management Plan 1995. To fish in the NPF operators must hold Statutory Fishing Rights (SFRs), which control fishing capacity by placing limits on the numbers of trawlers and the amount of gear permitted in the fishery. There are two types of SFRs: (i) a Class B SFR, which permits a boat to fish in the NPF; and (ii) a gear SFR, which limits the amount of net a fisher can use (Dichmont et al, 2014). The fishery is also subject to a range of spatial closures to protect seagrass beds and other sensitive habitats, as well as seasonal closures protect to small prawns, as well as to protect spawning individuals. The Tiger Prawn fishery is the most valuable component of the NPF and management of the NPF is primarily based around this part of the fishery (Dichmont et al, 2014). The Banana Prawn fishery is managed by a fixed length season, with some in-season management aimed primarily at allowing a maximum season length in highly productive years, and reducing the season length in years of low production. Levels of effort in the fishery are adjusted according to a formal harvest strategy structured around the two main ‘fisheries’: the ‘Tiger Prawn fishery’ and the ‘Banana Prawn fishery’ (Dichmont et al, 2014). In the Tiger Prawn fishery, the operational objective is to achieve maximum economic yield (MEY) with adjustments made as necessary to spatial and temporal closures, and/or gear to meet the MEY objective over a 7-year period. The outputs from a bio-economic model (which includes the biology of tiger and Endeavour Prawns, and key economic variables) are used to set the level of standardised effort for the fishery. In the Banana Prawn fishery, the operational objective is to allow sufficient escapement from the fishery to ensure an adequate spawning biomass of Banana Prawns (based on historical data), and to achieve the maximum economic yield (MEY) from the fishery. The length of the main fishing season for Banana Prawns is adjusted according to a set of structured decision rules designed to achieve MEY. In addition to the controls on effort for the main target species, Moreton Bay Bugs are subject to a number of species specific management measures. These include a 60 mm minimum carapace width and a prohibition on the take of ‘berried’ female bugs (Dichmont et al, 2014). In addition, a 100t trigger limit applies, which if breached triggers a review of logbook and trawl survey data to establish that catches are sustainable. The fishery is monitored through a compulsory daily catch and effort logbook, as well as through an annual fishery independent trawl survey undertaken in January/February and a biennial trawl survey undertaken in June/July. The fishery is also subject to a crew member observer program and a scientific observer program. In 2015, crew member observers undertook 1,058 monitoring days (12.9%) and scientific observers undertook 159 monitoring days (1.94%) (Larcombe et al, 2016). Milton et al (2010) used independent trawl survey data to estimate acceptable biological catch (ABC) levels for the main byproduct species taken in the NPF. For Moreton Bay Bugs, they estimated a mean ABC of 1,887t (95% c.i. 1,716 – 2,057). Since then, catches have remained well below the ABC, with catch peaking in 2013 at 109t. Although the harvest strategy for the NPF is designed around the main target species, estimates of sustainable catch levels for bugs have been made and existing harvest controls have been sufficient to consistently constrain catch well below those estimates. Catches continue to be monitored against a precautionary trigger point, which precipitates a review of available data if breached. To that end, the harvest strategy could be expected to be responsive to the state of the stock (if reviews following a breach of trigger limits identified a sustainability concern) and all of the elements appear to work together to meet the stock management objectives reflected in criterion 1A(i). Accordingly, we have scored this SI low risk. |

|||

|

Shark-finning |

|||

|

NA |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place. |

|||

|

(a) HCR Design and application |

MEDIUM RISK |

||

|

There is currently no well-defined harvest control rule for Moreton Bay Bugs, although the stock is subject to a trigger limit under the NPF harvest strategy which precipitates a review of available data if breached (Dichmont et al, 2014). Given catches have remained well below the estimated ABC for the stock, and the fact that HCRs have been used extensively by AFMA in the NPF and other fisheries, there is a strong argument that generally understood HCRs are in place and tools are available (e.g. spatial/temporal closures, adjustments to MLS) which could be expected to reduce exploitation if PRI was approached. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk. |

|||

|

PI SCORE |

MEDIUM RISK |

||

|

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy. |

||||

|

(a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Moreton Bay Bugs are distributed along the tropical and subtropical coast of Australia from northern New South Wales to Shark Bay in Western Australia. No studies have been carried out on the biological stock structure of Australian Moreton Bay Bugs. The two species (Thenus australiensis and T. parindicus) have overlapping distributions, may be trawled together, are undifferentiated in the catch and are thus typically assessed together (Zeller et al, 2016). While the biological understanding of these two species in northern Australia is incomplete, there is sufficient information to inform the harvest strategy. For example, Milton et al (2010) used independent trawl survey to estimate acceptable biological catch levels for the stock within the NPF. They also used Bayesian methods to undertake preliminary evaluations of a range of alternative management approaches including changes to the minimum legal size and levels of compliance. A number of studies have characterised the biology of Moreton Bay Bugs including growth, mortality and reproductive potential (e.g. Courtney, 1997; Stewart et al, 1997). Fleet composition is well understood and sufficient data are collected to support the harvest strategy (i.e. MLS and trigger limits) including catch and effort levels (verified by scientific and crew member observers), vessel details and spatial effort coverage through VMS data. |

||||

|

(b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

MEDIUM RISK |

|||

|

Moreton Bay Bugs are a byproduct species in the NPF, so stock abundance is not monitored in the same way as the main target species. The main ‘HCR’ in the fishery is the 100t catch trigger limit in the harvest strategy which precipitates a review of available information if breached. The trigger limit takes into account Milton et al’s (2010) estimates of ABC and has been set at a precautionary level. Removals from the UoA are very well monitored through catch and effort logbooks, verified by crew and scientific observer programs. Given the nature of the stock and absence of similar fisheries in the area, there are likely to be few if any removals from other fisheries. To that end, UoA removals are monitored and at least one indicator (catch) is monitored consistent with the ‘HCR’ for the stock. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk. Milton et al (2010) suggest that the NPF prawn monitoring surveys may provide a reliable index of Moreton Bay Bug abundance, although this stock is not regularly included in normal analysis of surveys results. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is an adequate assessment of the stock status. |

||||

|

(a) Stock assessment |

MEDIUM RISK |

|||

|

No formal quantitative assessment of the NPF Moreton Bay Bug stock exits, although Milton et al (2010) produced estimates of biomass and a possible ‘acceptable biological catch’ based on data from independent prawn surveys run between 2005 and 2007. They noted that they attempted to conduct a stock assessment using biomass dynamics models, however the models failed to produce reliable and reasonable results. The main difficulties included the short data timeseries (1998 – 2007) in the commercial logbooks, the fact that commercial logbook records are not a reliable proxy for species occurrence because fishers may not always retain byproduct when they catch them and as non-target species the catch and CPUE may not be a reliable index for abundance. Milton et al (2010) concluded that because catch has been well below their estimates of ABC, catches do not need close monitoring by managers unless fishing practices change dramatically. Accordingly, estimates of ABC have not been updated since. In addition to the monitoring of catch against the trigger point in the harvest strategy, the stock is also subject to regular ‘weight of evidence’ assessments as part of the FRDC Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks report (e.g. Zeller et al, 2016). These assessments classify status according to generic categories (e.g. ‘sustainable’, ‘overfished’, etc). Given that these assessments estimate status relative to generic categories and status in the NPF Harvest Strategy is assumed to be sustainable if catch remains below the 100t trigger level, there is an argument that assessments are undertaken which estimate status relative to generic ‘reference points’ which are appropriate to the species category. Accordingly, we have scored this SI medium risk. |

||||

|

(b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

MEDIUM RISK |

|||

|

Milton et al (2010) note that theirs was the first attempt to undertake some form of quantitative assessment of Moreton Bay Bugs in the NPF and also used new methods. As a result, there are several uncertainties in the assessment. Attempts were made to account for some uncertainties (e.g. by using multiple values for natural mortality), although other types of uncertainty may not yet be accounted for. The ‘weight of evidence’ approach used for the FRDC Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks report attempts to account for uncertainty by drawing from multiple sources of available information. The outcomes of these assessment are subject to peer review. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

MEDIUM RISK |

|||

Note: The NPF has been certified against the Marine Stewardship Council standard for the main prawn species since 2012. The certification covers the full geographic scope of the fishery. Assessments against Components 2 and 3 of this assessment are based on the information provided in the NPF’s MSC Public Certification Report (MRAG Americas, 2012) and subsequent surveillance audits. Unless otherwise specified, the Component 2 information is drawn from the assessment of the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery assessment.

[sta_anchor id=”C2″]COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI. |

||

|

(a) Main other species stock status |

LOW RISK |

|

|

The NPF scored 90 and 80 for retained and discarded species status respectively in its MSC assessment. For retained species the assessment concluded that “all retained species have been subject to a quantitative ecological risk assessment … These assessments, based on a robust methodology, provide a comprehensive evaluation of the retained species. Two mantis shrimps which were considered in theory to be at high risk in the Level 2 ERA, are being continuously monitored by observers but have never been recorded. Biologically-based limits, in the form of Acceptable Biological Catch (ABC) values which are catch limit reference values based on MSY exploitation rates and life history traits, have been estimated for four main groups of retained species (bugs, scallops, cuttlefishes and squids). Catches of the former three groups are well below the ABCs. Therefore, there is a high degree of certainty that these three groups are within biologically-based limits. Squid catches in the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery tally to only ~10% of the ABC for the NPF as a whole. Thus there is a high degree of certainty that squid catches in the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery are also within biologically-based limits even if for the NPF as a whole squid catches approached the ABC in 2007.” For discarded species, the assessment reported that “the status of the main bycatch species is considered to be well-known. A comprehensive assessment of bycatch species determined that of 507 species assessed, only four (blotched fantail ray, porcupine ray, dwarf lionfish and raggy scorpionfish) were at risk from the fishery because they exceeded a biologically-based limit. These four species were incorporated into the observer monitoring programme but no interactions with these species have yet been recorded. Scientists suggest that these four species may be hard bottom-associated, and thus outside the trawlable fishing grounds or that interactions are otherwise mitigated through TEDs. The risk assessment gave priority consideration to those species whose median estimates (50th percentile) of fishing mortality exceeded the reference points. It is not clear whether those species whose median estimate did not exceed, but whose 90% confidence interval (i.e. 95th percentile) did exceed, the reference point were consistently carried through to the expert override stage. However, given that none of the species with greater exceedances of the reference points (i.e. exceedance at 50th percentile versus 95th percentile) were ultimately found to be at risk, the probability that these other lower risk species are within biologically based limit is considered to be highly likely (80).” |

||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species; and the UoA regularly reviews and implements |

||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

|

The NPF scored 80 and 95 for retained and discarded species management respectively in its MSC assessment. For retained species, the assessment concluded that “there are formal measures in place for two of four key byproduct species groups: squid and bugs. Recent scientific evaluation has evaluated current catches and estimated acceptable biological catches for squid, bugs, cuttlefishes and scallops, and no instances of overfishing were identified. A more complete Non-Key Commercial Species (Byproduct) Policy is also being developed. It can therefore be concluded that there is a partial strategy currently in place (80). More recently, specific measures have been included in the NPF Harvest Strategy for the main byproduct species, including scampi and squid (Dichmont et al, 2014). For discarded species, the assessment noted “the Bycatch Action Plan (BAP), in conjunction with mandatory use of TEDs/BRDs, use of risk assessments of all species to identify high risks, and the observer monitoring programme for priority species, constitutes a strategy for managing and minimizing bycatch. Periodic updates of the Ecological Risk Management document assure that the strategy remains up to date. The strategy is based directly on the NPF and scientific testing has proven that substantial bycatch reduction will result from proper use of the devices. These methods have been used successfully in other similar fisheries.” The most recent MSC surveillance audit noted that the Northern Prawn Fishing Industry (NPFI) has initiated its Bycatch Management Strategy (NPFI, 2015), with a commitment to reduce bycatch by 30% by July 2018 (MRAG Americas, 2017). This is based on AFMA’s Bycatch and Discarding Workplans, which have replaced Bycatch Action Plans since 2008. Early indications are that the NPFI has responded positively in implementing the strategy with the development of Kon’s Covered Fisheyes BRD, where initial trials have led to the reduction in bycatch by 36.7% in the Tiger Prawn fishery (NPFI, 2017). The current approved BRDs will remain in legislation until 30 June 2018, then a review of BRDs will be undertaken and less effective devices will be removed from the “approved” list. |

||

|

LOW RISK |

||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) concluded for retained species that “the partial strategy is based on the ABCs (limit reference points), life history characteristics of the main retained species, and ongoing monitoring of these species. The results of the monitoring demonstrate that biologically-based limits are not being exceeded for the species covered by the partial strategy, thus there can be some confidence that the partial strategy is working (80) and is being implemented successfully by NORMAC and AFMA (80).” For discarded species they concluded that “the NPF claims to have reduced bycatch by 50% but since bycatch quantity and species composition is not routinely monitored, there is only indirect evidence of successful implementation (i.e., reductions in ETP species interactions, which presumably mean TEDs/BRDs are working effectively and thus presumably having an effect on non-ETP species as well). Therefore, there is some evidence that the strategy is achieving its objective (100). However, some concerns have been expressed about the positioning of BRDs for maximum effectiveness, and lacking further evidence of the successful implementation of bycatch reduction for bycatch species per se, and the lack of any recording of high priority bycatch species by observers, the evidence for the success of the strategy for bycatch species is not entirely clear (80).” Since the original assessment, subsequent surveillance audits have reported that species identified as being at risk through the NPF Ecological Risk Assessment process have been monitored through the crew member and scientific observer programs, as well as through fishery independent trawl surveys (MRAG Americas 2017). |

||

|

(c) Shark-finning |

||

|

NA |

||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Information on the nature and amount of other species taken is adequate to determine the risk posed by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage other species. |

||

|

(a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|

|

The NPF scored 85 and 80 for retained and discarded species information performance indicators respectively in its MSC assessment. For retained species, MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “quantitative data on all retained species is required by the mandatory logbook format of the NPF and the entire catch is represented in the logbook data. However, some similar species are recorded in combined, non-species-specific reporting categories because the species are not common and difficult to separate. This level of detail is deemed adequate by the management system because level 2 risk assessment has been conducted for essentially all of the species nordmally encountered. It is the case that recorded quantities in logbooks may not reflect abundance since retention and reporting rates may vary based on fishery operational costs, prawn and byproduct prices, prawn and byproduct catch rates, and vessel crew behaviour. Crew member observers and scientific observers also collect information on all retained species encountered. Scientific studies of actual catches versus acceptable biological catches have recently been completed for four main groups of byproduct species: squids, cuttlefishes, bugs and scampi. These concluded that recent annual catches of each byproduct group are a small proportion of the estimated biologically-sustainable total annual catch for those groups, except for squid which was near, but below, the biologically-sustainable level. Squid catches were found to be highly variable between years and the need for further study was noted”. For discarded species, MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that “several comprehensive scientific surveys have been conducted to assess the bycatch in the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery. Several quantitative ecological risk assessments have been undertaken using state-of-the-art methods. However, bycatch data collection from the fishery itself is not required by the logbook reporting format. Crew member observers and scientific observers focus their efforts on a list of four priority bycatch species defined through the ecological risk assessment process and ETP species. As a result, there is no ongoing operational data collection on total bycatch quantities or species composition. Research has been conducted to investigate the sample sizes required to detect statistically significant changes in the abundance of rarer (and thus of greater concern) bycatch species, but this research concluded that in most cases the sampling effort is beyond practically achievable levels”. |

||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species. |

||||

|

(a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The NPF scored 90 for the ETP species status PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that “direct and indirect fishery effects and their impacts on ETP species have been accounted for in the ecological risk assessments and no species in any of the five groups (marine mammals, seabirds, marine reptiles, elasmobranchs, and teleosts) have been assessed as “at risk”. Furthermore, the Australian government’s export certification process has declared that the NPF meets the requirements of the EPBC Act. Therefore there is a high degree of certainty that all national and relevant international requirements with regard to ETP are met (100). Despite the fact that impacts are considered acceptable, there is acknowledgement that some risks still exist. The NPF notes that recent BRD implementation has not proven effective at reducing seasnake catch in the NPF when set at the maximum legal distance from the codend. There are also concerns that cumulative impacts to sawfishes have not been adequately accounted for and that interaction rates have not been adequately reduced by TEDs due to sawfish rostrum entanglement. Therefore, while direct and indirect impacts are considered acceptable, they may still be significant and are the subject of continuing research (80).” The most recent surveillance audit reviewed the latest information on ETP species interactions, and found no justification to alter the original scoring (MRAG Americas, 2017). |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

Also, the UoA regularly reviews and implements measures, as appropriate, to minimise the mortality of ETP species |

||||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The NPF scored 95 for the ETP species management PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “the NPF has formulated and implemented a Bycatch and Discarding Work Plan (BDWP) and an Ecological Risk Management Strategy, which encapsulate the NPF’s strategy for overall minimisation of bycatch through developing management responses to high ecological risks and measures to avoid fishery interactions with species listed under the EPBC Act. This strategy comprises temporal and spatial closures, monitoring programmes, research projects and bycatch reduction activities such as development and testing of new BRDs. As none of the ETP species have been found to be at high risk from the fishery, the main management achievements for ETP species have been in the form of bycatch reduction, in particular turtle bycatch has been reduced by 99%. However, TEDs and BRDs have had mixed success for other organisms: one study reported that TEDs reduced catches of narrow sawfish by 73% whereas other studies found only a slight effect or no effect due to entanglement before the TED is contacted. Similarly for seasnakes, research results showed that BRDs did not effectively reduce bycatch when placed at the maximum legal distance from the codend, although they did reduce crushing of caught seasnakes and thus improved survival.” On the basis of the available information, they concluded that “there is a strategy in place to manage the fishery’s impacts on ETP species. Given that none of these species have been found to be at risk from the fishery, current levels of impacts (interactions) are considered to exceed national and international requirements for these species’ protection”. |

||||

|

(b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that:

|

||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

|

||||

|

(a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The NPF scored 85 for the ETP species information PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “There are two types of data available to estimate the impacts of the fishery on ETP species: comprehensive, but spatial and temporally limited research studies; and ongoing monitoring of the fishery itself. The former was used as the basis for the quantitative ecological risk assessment, which found that no ETP species are at risk from the fishery. However, it was acknowledged that cumulative impacts may need to be better accounted for in the methodology, particularly for those species that are known to be regionally/globally threatened such as sawfishes (CITES Appendix I listed for all but one species which is CITES Appendix II; IUCN Red List Critically Endangered). The monitoring data are designed to indicate trends in interactions between ETP species and the fishery. In the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery, ETP monitoring data are provided by NPF logbooks, the crew member observer programme and the scientific observer programme. The two observer programmes have coverage of 5% and 2.5%, respectively [12.9% and 1.94% in 2015; Larcombe et al, 2016]. ETP species interaction rates recorded in logbooks and by crew member observers are generally much lower, and are less likely to be species-specific, than those recorded by scientific observers. For a variety of reasons, species specific identifications are not always provided (e.g., in some cases, obtaining a species identification could work against the live release of the organism (sawfishes)). This, in combination with low catch rates, makes it difficult to analyse the data for changes in abundance. A study examining the requisite sample sizes to detect a statistically significant difference found that the number of samples required to assess rare species is well beyond practical limits of the observer and monitoring programmes; therefore, other strategies were recommended.” Based on this, they concluded that “the combination of quantitative ecological risk assessment and ongoing fishery monitoring is sufficient to determine whether the fishery is a threat to ETP species; to measure trends; and to support the Bycatch and Discarding Work Plan and Ecological Risk Management Strategy”. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to habitat structure and function, considered on the basis of the area(s) covered by the governance body(s) responsible for fisheries management |

|||

|

(a) Habitat status |

LOW RISK |

||

|

The NPF scored 100 for the habitat status PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas reported that “the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery is believed to have the greatest potential for benthic habitat impacts because it is most closely associated with the seabed of the three NPF sub-fisheries. However, none of the 157 habitat types (benthic and water column) evaluated under the Level 2.5 ecological risk assessment were found to be at high risk. Throughout the NPF fishing effort is concentrated in a 3-month period and occurs over only about 3% of the managed region. One study found that over a 5-year period only 17% of the managed region was trawled at all. The trawled “hotspots” tend to change from year to year such that only a very small proportion of the fished area of the NPF makes up the same hotspot every year. Recent studies in the Gulf of Carpentaria involving sampling of sites that were subject to high, medium and low intensity trawling in three of the fishing grounds/habitats defined (Groote, Mornington and Vanderlins) found that trawling intensity explained only 2% of the biomass density variation in epibenthic invertebrates (including benthic sessile and mobile species), and at most 1% in infaunal invertebrates. Sessile or slow-moving taxa were found to recover from the effects of intensive trawling within 6-12 months. Findings’ indicating that trawling has little effect on the infaunal community suggest that trawling also has relatively little effect on the majority of benthic habitats within the NPF. The connection between habitat and community is particularly strong in the case of habitat-forming organisms such as gorgonians, soft corals and sponges found in this highly dynamic environment. These same studies found no unique, exclusive habitats and noted that the majority of the ecologically important habitats are located in untrawlable areas. Some areas of high biodiversity such as marginal reefs and sponge gardens can be found within trawlable areas but these may not be permanent structures given the high natural environmental disturbance regime (e.g., storm surges, tides, flooding and cyclones).” The most recent surveillance report (MRAG Americas, 2017) recognised new analysis of the trawl footprint in the context of habitats in the NPF area (Pitcher et al, 2016). The surveillance report summarised the main outcomes of the analysis as follows: “About 19.6% of the NPF area (0‐150 m) is closed in CMR[2]s, ~0.2% in MPAs and ~0.7% under fishery regulation — the total closed is 20.5%. The annual footprint of the NPF trawl fishery is 1.6% overall, with most trawling around the perimeter of the Gulf of Carpentaria in assemblages ‘9’ (main habitat for the Tiger Prawn subfishery) & ‘2’ (main habitat for the white Banana Prawn subfishery), with footprints of 13% & 5.7% trawled annually about 1.9 & 1.4 times on average, hence total swept ratios are 24.7% & 7.9% respectively. These footprints are indicative of the relative potential for habitat risk and priority for future AFMA habitat ERAs”. The surveillance audit concluded there was no justification to change the original scoring. |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the habitats. |

|||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

||

|

The NPF scored 80 for the habitat management PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “habitat impacts are primarily managed through a system of spatial and temporal closures adopted by the NPF to protect vulnerable habitats such as seagrass beds and coral and rocky reefs, as well as to address economic objectives of the fishery. A total of 2.1% of the managed zone of the fishery is subject to permanent closures while 8.3% is subject to seasonal closures. These areas include all known seagrass beds. Furthermore, the entire fishery is closed for 5.5 months each year. It has been noted that with the decline in fishing effort from 286 vessels in 1981 to 52 vessels in 2009, and the deployment of these vessels of between 8-17% of the NPF-managed region overall and only intensively over about 3% per year (concentrated in a 3-month period), residual habitat impacts from trawls contacting the seabed are expected to be further minimized. Since ecological risk assessments on habitats found little or no detrimental impact on the physical marine environment, AFMA has deferred development of an ecological risk management strategy for NPF habitats until more information is available.” |

|||

|

(b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that “the partial strategy is based on known ecological valuable habitats located within the NPF fishing grounds and there is confidence it will work through VMS monitoring to demonstrate avoidance of closed areas. Some evidence for implementation of the partial strategy is provided in the form of VMS monitoring of vessel movements with regard to the spatial and temporal closure requirements, and by the low number of observed interactions with seagrass bed-associated species such as dugongs and syngnathids.”

|

|||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Information is adequate to determine the risk posed to the habitat by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage impacts on the habitat. |

|||

|

(a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

||

|

The NPF scored 95 for the habitat information PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “all habitats in the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery were mapped for the ecological risk assessment. The impacts of the trawl gear’s interaction with these habitat types were evaluated and none of the habitats were found to be at high risk. A number of historical and recent in-depth research projects have, in combination, produced a digital spatial library describing the state, composition and spatial variability of the NPF’s habitats. Areas that have been subject to trawling, as well as those that have not, have been identified and the time required for the habitat to recover from trawl-related disturbance has been investigated through quantitative field experiments and simulation modelling. Ongoing information gathering is mainly in the form of VMS monitoring of vessel behaviour with regard to the temporal and spatial closures. While other research studies on habitats may be undertaken in the future, this work is not an ongoing feature of NPF management”. |

|||

|

(b) Information and monitoring adequacy |

LOW RISK |

||

|

On the basis of the available information, MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that “Monitoring of fishing effort and total area fished would demonstrate if effort or area increased, which would detect a potential change in risk to the habitat. The physical impact of the gear on habitat types has been extensively studied through field experiments and simulation”. |

|||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to the key elements of ecosystem structure and function. |

||

|

(a) Ecosystem Status |

LOW RISK |

|

|

The NPF scored 100 for the ecosystem status PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “the ecosystem effects of the NPF’s trawl fisheries have been studied in depth, most recently in studies involving both field surveys/experimentation (e.g. sampling of sites that were subject to high, medium and low intensity trawling in a number of fishing grounds) and simulation models. These studies have focused on the Tiger Prawn sub-fishery (Gulf of Carpentaria), which has the highest diversity of catch. The most recent of these studies, completed in 2010, concluded that the effects of trawling at the current scale of the NPF do not affect overall biodiversity and cannot be distinguished from other sources of variation in community structure. Specifically, trawling intensity explained only 2% of the biomass density variation in epibenthic invertebrates (including benthic sessile and mobile species), and at most 1% in infaunal invertebrates. Community composition and structure were more strongly related to region, and in some cases time of day, than to the intensity of trawling. Nevertheless, mean trophic level was shown to have declined when the fishery was at its peak in the early 1980s and rose again when fishing effort dropped. The study found that communities can recover rapidly when trawling frequency is reduced. In addition to these studies of the benthic community, a Level 1 risk assessment (based on a Scale Impact Consequence Analysis) concluded that impacts to the ecosystem were of low consequence. The assessed risks, the field studies of impacts, and the monitoring undertaken for the species assessed elsewhere under this principle (P2), further support the lack of disturbance to key components of the ecosystem and thus suggest a lack of disturbance to ecosystem structure and function.” |

||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There are measures in place to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem structure and function. |

||

|

(a) Management Strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

|

The NPF scored 90 for the ecosystem management PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “the Ecological Risk Management (ERM) document for the NPF states that it does not contain specific management strategies for habitats and communities; however, it does contain measures to prevent adverse impacts to species (through quantitative ecological risk assessment, list of priority species for monitoring, and catch monitoring and reporting requirements) and measures to prevent adverse impacts to habitats (through temporal and spatial closures and VMS monitoring of the location and duration of trawling impacts). Therefore, while the ERM document cannot be considered a full strategy premised on functional relationships between the fishery and the ecosystem, it certainly represents a partial strategy. Evidence that this partial strategy is likely to work and is being implemented is available in the form of species and VMS monitoring data, which are subject to ongoing scrutiny, as well as updates to the ecological risk assessment process and changes to monitoring procedures as necessary. Several research studies have also been conducted to assess the effectiveness of management practices (e.g., TEDs/BRDs) for bycatch and ETP species groups in particular.” |

||

|

(b) Management Strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|

|

MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that “the elements of the ERM document have been tested and proven to work through experience in the fishery involved, as confirmed by comprehensive research studies and reports. Evidence for effective implementation exists in the form of successful lowering of interaction rates with some groups of ETP species, large reductions in the overall amount of bycatch, and VMS monitoring of temporal and spatial closures.” |

||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) There is adequate knowledge of the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem. |

||

|

(a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

|

|

The NPF scored 90 for the ecosystem information PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “detailed ecosystem studies have been conducted for the NPF in the Gulf of Carpentaria focused on the Tiger Prawn subfishery. These studies have comprised both field surveys/experiments and simulation models and addressed the issue of the impacts of trawling from many angles. While these research projects have been given generous, multi-year funding, they are not an ongoing component of NPF management. Two issues have been highlighted for further study: the identification of proper control sites for impact assessment, and the effects of trawling on high biodiversity areas (e.g., sponge gardens) within trawlable fishing grounds. A recent study has integrated bioeconomic stock and ecological risk assessment models with food web, effect of trawling and species distribution models to form an operational spatial management strategy evaluation framework. This tool will facilitate NPF ecosystem-based fisheries management.” |

||

|

(b) Investigations of UoA impacts |

LOW RISK |

|

|

MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that “The main functions of ecosystem components are known through field investigations and computer simulation; however, the impacts of the fishery on all species and habitats are yet to be fully understood. Research studies have provided sufficient information to understand the main ecosystem consequences for components (e.g., trophic levels), though not necessarily elements (e.g., species). Existing information appears to be sufficient to develop strategies to manage ecosystem impacts; however, it is noted that as serious and/or irreversible ecosystem impacts have not been identified, no such strategies have as yet been developed. The main interactions between the fishery and the ecosystem elements have been investigated in detail.” |

||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|

[sta_anchor id=”C3″]COMPONENT 3: Management system

|

CRITERIA: (i) The management system exists within an appropriate and effective legal and/or customary framework which ensures that it:

|

||||

|

(a) Compatibility of laws or standards with effective management |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “overarching Commonwealth legislation relevant to fisheries includes the (1) Fisheries Management Act of 1991 and (2) the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act 1999. The FMA takes account of the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement and FAO’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. AFMA has also adopted the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management through the Ecological Sustainable Development Policy and its overarching framework for Commonwealth fisheries (AFMA, 2005). The Ecologically Sustainable Development Policy ESD includes the principles of ecologically sustainable target and bycatch species, ecological viability of bycatch species, and impact of the broader marine ecosystem”. Accordingly, there is an effective national legal system to deliver on the outcomes expressed in Components 1 and 2. |

||||

|

(b) Respect for Rights |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) report that “special provision for ‘traditional fishing’ is made where they might apply in the contexts of both Commonwealth and State Fisheries Law. The Northern Prawn fishery is a specialist offshore commercial fishery. Indigenous rights are however considered in the context of The Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT) s 12(1) which empowers the Administrator to close the seas adjoining and within 2km of Aboriginal land, to others who are not Aborigines entitled by tradition to enter and use the seas in accordance with that tradition. Before doing so he may (and in case of dispute he must) refer a proposed sea closure to the Aboriginal Land Commissioner. These issues are taken into account through NOPRMAC consultation processes and in the context of closed areas discussions. Once seas are closed it is an offence for a person to enter or remain on these seas without a permit issued by the relevant Land Council”. In addition, Fisheries Legislation Amendment (Representation) Bill 2017 is currently before the Commonwealth parliament. The Bill provides for explicit recognition of recreational and Indigenous fishers in Commonwealth legislation and requires AFMA to have regard to ensuring that the interests of all fisheries users are taken into account in Commonwealth fisheries management decisions[3]. Given the above, the management system has a mechanism to observe the legal rights created explicitly or established by custom of people dependent on fishing for food or livelihood. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The management system has effective consultation processes that are open to interested and affected parties. The roles and responsibilities of organisations and individuals who are involved in the management process are clear and understood by all relevant parties. |

||||

|

(a) Roles and Responsibilities |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The roles and responsibilities of the main people (e.g. Fisheries Minister, AFMA Commissioners) and organisations (AFMA) involved in the Australian Commonwealth fisheries management process are well-understood, with relationships and key powers explicitly defined in legislation (e.g. FMA, FAA) or relevant policy statements (e.g. AFMA Fisheries Management Paper 1 – Management Advisory Committees). MRAG Americas (2012) report that “AFMA undertakes the day to day management of the Commonwealth fisheries under powers outlined in the FMA and Fisheries Administration Act 1991. Overarching policy direction is set by the Australian Government through the relevant Minister responsible for fisheries, acting upon advice from the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Roles and responsibilities are divided between the respective management organisation (AFMA), the Northern Prawn Industry Pty Ltd, the Northern Prawn Management Advisory Committee (NORMAC) and Northern Prawn Resource Advisory Group (NPRAG)”. |

||||

|

(b) Consultation Process |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) report that:

These arrangements meet the low risk SG. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) The management policy has clear long-term objectives to guide decision making that are consistent with Components 1 and 2, and incorporates the precautionary approach. |

||||

|

(a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) note that “the long term objectives of the management system are specified in the FMA and the EPBC Act, and further defined in the Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy and Guidelines. The objectives and policy guidance are consistent with MSC’s Principles and Criteria and explicitly require application of the precautionary principle. The fishery is also subject to the Commonwealth EPBC Act which requires periodic assessment against the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries. These Guidelines are consistent with the MSC Principles and Criteria and encourage practical application of the ecosystem approach to fisheries management”. These arrangements are consistent with the low risk SG. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

3B: Fishery Specific Management System |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The fishery specific management system has clear, specific objectives designed to achieve the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2. |

||||||

|

(a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) note that “The Northern Prawn Fishery Management Plan 1995 reinforces the objectives of the FMA as the objectives of the Plan. Fishery specific objectives can be identified in the Northern Prawn Fishery Harvest Strategy under Input Controls, 2011, and updated annually. The Strategy contains references to use of measurable indicators such as target and limit reference points. Other management documents containing fishery-specific objectives relating to the fishery include the Bycatch Action Plan (BAP), and the NPF Industry Code of Practice. Management outcomes are provided in the BAP and the Strategic Assessment report to DSEWPac (AFMA (2008b).” |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The fishery specific management system includes effective decision making processes that result in measures and strategies to achieve the objectives and has an appropriate approach to actual disputes in the fishery. |

||||||

|

(a) Decision making |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) note that “the decision making processes by AFMA based on advice from NORMAC (working with NPF RAG and the NPF Research and Environment Committee (NPF REC)) are transparent with feedback provided by the Commission directly to NORMAC and to stakeholders through media such as the regular AFMA Update and through the Annual public meeting of both the MAC and AFMA. The decision making process for the NPF is consistent with those for the broader management system and responds to the defined harvest and bycatch management strategies, which respond to research, outcomes evaluations and monitoring programmes.” On this basis, they concluded that “decision-making processes respond to all issues identified in relevant research, monitoring, evaluation and consultation, in a transparent, timely and adaptive manner and take account of the wider implications of decisions”. |

||||||

|

(b) Use of the Precautionary approach |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The precautionary approach is explicitly required in both the FMA and the NPF Management Plan. A practical example of the precautionary approach being applied is the assumption of higher risk in the ERA process where uncertainty exists in the input parameters. |

||||||

|

(c) Accountability and Transparency |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “the AFMA website contains an extensive list of evaluations, research reports and assessments, and evidence exists within the NORMAC and the NPFRAG that decisions respond to these findings”. They also noted that “formal reporting to all interested stakeholders describes how the management system responded to findings and relevant recommendations emerging from research, monitoring, evaluation and review activity”. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms ensure the management measures in the fishery are enforced and complied with. |

||||||

|

(a) MCS Implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The NPF scored 100 for the compliance and enforcement PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “the management system takes a risk-based approach to compliance. Compliance risk assessments are undertaken in consultation with the industry, and compliance plans are developed for the NPF fishery by AFMA. Primary compliance tools include vessel monitoring systems on all vessels, prior to landing-reports, catch disposal records and fish receiver records. At-sea and in-port vessel inspection, fish receiver inspections, and trip and landing inspections are carried out. There are appropriate provisions for penalties for infringement of fishery management measures in the FMA”. They concluded that “a comprehensive monitoring, control and surveillance system has been implemented in the fishery under assessment and has demonstrated a consistent ability to enforce relevant management measures, strategies and/or rules”. |

||||||

|

(b) Sanctions and Compliance |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

A framework of sanctions for non-compliance is set out in the FMA, Maritime Powers Act 2013 and Fisheries Management Regulations 1992. These include powers to issue warnings, cautions, directions, Observer Compliance Notices, Commonwealth Fisheries Infringement Notices (CFINs), amend fishing concession conditions, suspend or cancel fishing concessions and prosecute offenders through the courts (AFMA, 2015a). Evidence exists that fishers comply with the management system including providing information of importance to the effective management of the fishery. Across all years between 2011-12 and 2015-16, no action was required in >90% of boat inspections in Commonwealth fisheries (total inspections 879) (AFMA, 2015b). MRAG Americas (2012) noted that “AFMA acts on intelligence provided and there is a considerable degree of peer pressure applied within the industry to ensure compliance. This is also cemented by the NPF Code of Conduct which ensures the application of best practice such as reporting ETP interactions, and applying appropriate handling practices.” Overall, they concluded that “sanctions to deal with non-compliance exist, are consistently applied and demonstrably provide effective deterrence”. |

||||||

|

LOW RISK |

||||||

|

MRAG Americas (2012) concluded that there is no evidence of systematic non-compliance in the fishery and there is a high degree of evidence fishers comply with the management system. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iv) There is a system for monitoring and evaluating the performance of the fishery specific management system against its objectives. |

||||||

|

(a) Evaluation coverage |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Performance of all stocks against the NPF Harvest Strategy are assessed annually through the NPRAG and NORMAC process. Periodic updates of ERAs evaluate performance against environmental objectives and guide management priorities. Fishery Status Reports produced annually by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) provide an independent evaluation of key parts of the management system (e.g. stock status, overfishing status). In addition, two Australian National Audit Office reviews have been undertaken into the domestic compliance program (ANAO, 2009; 2013). Accordingly, the fishery has measures in place to evaluate key parts of the management system. |

||||||

|

(b) Internal and/or external review |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The NPF scored 100 for the monitoring and management performance evaluation PI in its MSC assessment. MRAG Americas (2012) reported that “AFMA’s management system is subject to internal and external performance evaluation including: Internal peer reviews, which include:

External reviews, which include:

CSIRO research results are often published in peer reviewed scientific journals. DSEWPac undertake an assessment of the fisheries management activities against the principles outlined in the EPBC Act. There is a regular review of the bycatch programme and a very high level of assessment applied to retained, bycatch, habitat, ecosystem and ETP species.” |

||||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||||

AFMA (2015a). National Compliance and Enforcement Policy 2015. 31pp.

AFMA (2015b). National Compliance and Enforcement Program 2016 -17. 45pp.

Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) (2009), Management of Domestic Fishing Compliance, audit report no. 47 2008-09.

Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) (2013). Administration of the Domestic Fishing Compliance Program. 128pp.

Courtney, A. (1997). A study of the biological parameters associated with yield optimisation of Moreton Bay Bugs, Thenus spp. Final Report (Project #92/102).

Dichmont, C., Jarrett, A., Hill, F. and Brown, M. (2014). Harvest strategy for the Northern Prawn Fishery under input controls, AFMA, Canberra.

Larcombe, J., Bath, A. and Green, R. (2016). Chapter 5 Northern Prawn Fishery. In ABARES 2016, Fishery status reports 2016, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra. CC BY 3.0.

Milton, D., Fry, G., Kuhnert, P., Tonks, M., Zhou, S. and Zhu, M. (2010), Assessing data poor resources: developing a management strategy for byproduct species in the Northern Prawn Fishery, final report to the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, project 2006/008.

MRAG Americas (2012). Public Certification Report for Australian Northern Prawn Fishery. 399pp.

MRAG Americas (2017). Surveillance Audit Report for The Australian Northern Prawn (Twin, triple and quad otter trawl) Fishery: 4th Surveillance Report. 21pp.

MRAG Asia Pacific (2015). Coles Responsibly Sourced Seafood Assessment Framework. 12pp.

NPFI (2015). Northern Prawn Fishery Bycatch Strategy, 2015-2018.

Pitcher, C.R., Ellis, N., Althaus, F., Williams, A., McLeod, I., Bustamante, R., Kenyon, R., Fuller, M. (2016) Implications of current spatial management measures for AFMA ERAs for habitats — FRDC Project No 2014/204. CSIRO Oceans & Atmosphere, Published Brisbane, November 2015, 50 pages.

Stewart, J., S.J. Kennelly and O. Hoegh-Guldberg (1997). Size at sexual maturity and the reproductive biology of two species of scyllarid lobster from New South Wales and Victoria, Australia. Crustaceana 70: 344-367.

Zeller, B, Larcombe, J. and Kangas, M. (2016). Moreton Bay bugs Thenus parindicus, Thenus australiensis, Thenus spp. in Carolyn Stewardson, James Andrews, Crispian Ashby, Malcolm Haddon, Klaas Hartmann, Patrick Hone, Peter Horvat, Stephen Mayfield, Anthony Roelofs, Keith Sainsbury, Thor Saunders, John Stewart, Ilona Stobutzki and Brent Wise (eds) 2016, Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2016, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.