Gould’s Squid – Commonwealth Trawl Sector

Assessment Summary

Gould’s Squid

Unit of Assessment

Product Name: Gould’s Squid

Species: Nototodarus gouldii

Stock: Gould’s Squid – South eastern Australia

Gear type: Otter Trawl

Fishery: Commonwealth Trawl Sector

Year of Assessment: 2017

Fishery Overview

This summary has been adapted from Helidoniotis et al (2017a):

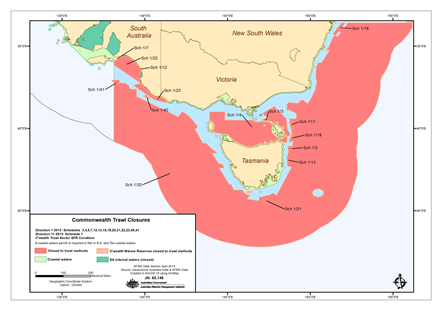

The Commonwealth Trawl Sector (CTS) of the Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (SESSF) stretches from Sydney southwards around Tasmania to Cape Jervis in South Australia, where it abuts the Great Australian Bight Trawl Sector (GABTS; Figure 1). The CTS and Scalefish Hook Sector (SHS) are major domestic sources of fresh scalefish for the Sydney and Melbourne markets, and there is minimal international export from these fisheries.

Figure 1: Relative fishing intensity in the CTS in the 2016-17 fishing season. (Source: Helidoniotis et al, 2017a).

The SESSF is a multisector, multigear and multispecies fishery, targeting a variety of fish and shark stocks using different gear types in different areas or depth ranges. Effort in the SESSF is distributed across all fishery areas, but since about 2005 has become increasingly concentrated on the shelf rather than in slope or deeper waters. The CTS predominantly uses otter trawl and Danish-seine methods. Pair trawling and midwater trawling methods are also permitted under the SESSF management plan.

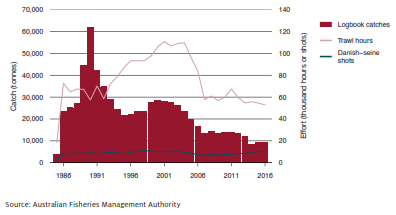

In 2016–17, trawlers reported 52,215 hours of fishing effort, representing a decrease from the 54,078 hours in 2015–16 (Figure 2). The number of active trawlers decreased slightly from 37 vessels in 2015–16 to 34 vessels in 2016–17. The total landings of all species in the CTS in 2016-17 was 8,691t, down slightly from the 9,025t taken in 2015–16. Flathead, Blue Grenadier, Pink Ling, eastern school whiting and Orange Roughy (eastern zone) accounted for approximately 77 per cent of the catch.

Figure 2: Total catch and fishing effort in the CTS, 1985 to 2016. (Source: Helidoniotis et al, 2017a).

Figure 3 Catch trends

Risk Scores

|

Performance Indicator |

Risk Score |

|

LOW |

|

|

1A: Stock Status |

LOW |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

LOW |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

LOW |

|

C2 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF FISHING |

MEDIUM |

|

LOW |

|

|

2B: ETP Species |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH |

|

2C: Habitats |

LOW |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

LOW |

|

C3 MANAGEMENT |

LOW |

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

LOW |

Summary of main issues

- Most of the main stocks are well-positioned against Component 1 performance indicators, except for Eastern Gemfish where, despite recent years of low total catch, predicted recovery has not yet occurred.

- The fishery appears relatively well-placed against most of the Component 2 performance indicators, although there is uncertainty about whether existing arrangements are sufficient to ensure stock rebuilding for Blue Warehou and Eastern Gemfish.

- The fishery is well-positioned against P3 performance indicators.

Outlook

| Component | Outlook | Comments |

| Target species | Stable = | Fishing effort is currently low in the context of historical effort levels, influenced by economic conditions. |

| Environmental impact of fishing | Stable = | Lower risk scores may be achieved with additional evidence that measures in place to ensure the CTS does not hinder recovery of ETP species are being implemented successfully. |

| Management system | Stable = | No major changes are expected to Component 3 PIs |

COMPONENT 1: Target species

1A: Stock Status

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing.

| (a) Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

Genetic studies support the hypothesis of a single biological stock of Gould’s Squid throughout south-eastern Australian waters (Noriega et al, 2016).

Noriega et al (2016) report that “no formal stock assessment is available for the Gould’s Squid biological stock in Australia. Gould’s Squid is short lived (less than 1 year), spawns multiple times during its life, and displays highly variable growth rates, and size and age at maturity1. These characteristics mean that the population can rapidly increase in biomass during favourable environmental conditions; it is therefore less susceptible to becoming recruitment overfished than longer-lived species. However, as the fishery targets individuals less than 1 year of age, there is potential for the population to be recruitment overfished if insufficient animals survive long enough to reproduce.”

Emery and Bath (2017) report that:

- In 2008, the Squid Resource Assessment Group analysed catch, catch rates and effort since 2000 for four regions in the SSJF. Only one region—the central region from Cape Otway in Victoria to Robe in South Australia—had levels of fishing that could cause substantial depletion. During the 2001 fishing season, high catch rates were reported for the central region, and the total jig fishery catch was the second highest on record. A preliminary depletion analysis of the central region using jig catch-and-effort data indicated that, despite the high catches, the stock was not overfished in that region in that year.

- ABARES conducted further depletion analyses for the central region of the SSJF for 1995 to 2006 (Barnes et al. 2015). The initial depletion curve results show declines in stock during most seasons, with escapement in five seasons estimated to be between 30 and 40 per cent. However, these results are for only one region of the fishery and do not indicate exploitation rates for the whole stock. Limited data are available on squid growth in this region. Interpretation of the depletion estimates is further complicated by the lack of an agreed estimate of natural mortality, the possible presence of multiple cohorts each year (as a result of multiple spawning events) and a lack of knowledge about squid movement in the region.

- Trawl catch rates from the CTS have been stable over the past 15 years, suggesting long-term stability in the availability, and perhaps biomass, of Gould’s squid in the areas trawled. The 2012 average trawl catch rate for Gould’s squid in the CTS was the highest reported in the past 20 years. The extent to which squid are targeted on trawl grounds is unclear.

- The high historical catches taken by foreign vessels in the late 1970s and 1980s indicate that a high annual harvest can be taken from the stock in years of high abundance without greatly reducing recruitment and biomass for subsequent seasons. The results of retrospective depletion analysis, stable catch rates in the trawl fishery over an extended period and high average catch rates (with the exception of the 2014 season, when effort declined) indicate that the stock has not yet been overfished in any season.

On the basis of the above, they conclude that the stock is not overfished.

Although there is limited empirical evidence estimating a conventional BMSY or proxies, the weight of available evidence suggests the stock is currently being fished at very low levels and probably highly likely to be above the point of recruitment impairment. The fact that overall catch and effort in recent years has been is substantially lower than in 2001 when a preliminary depletion analysis suggested the stock was not overfished, provides a plausible argument to suggest there is no reason why the stock is not capable of producing maximum sustainable yield based on environmental drivers.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

1B: Harvest Strategy

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place.

| (a) Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

|

The CTS harvest strategy consists of:

- Limited entry;

- Catch controls through TACs and ITQs, set according to well-defined harvest control rules under the SESSF Harvest Strategy Framework (HSF; AFMA, 2017);

- Gear restrictions;

- Monitoring through logbooks and catch disposal records (CDRs);

- Monitoring through VMS;

- Monitoring through independent observers who provide estimates of discards; and

- Periodic assessments of stock status.

A harvest strategy framework (HSF) has been in place in the SESSF since 2005. The most recent version of SESSF Harvest Strategy was agreed in 2017 (AFMA, 2017a). The SESSF HS is designed to meet the objectives of the Commonwealth Fisheries Harvest Strategy Policy 2007 (HSP), namely “the sustainable and profitable use of Australia’s Commonwealth fisheries in perpetuity through the implementation of harvest strategies that maintain key commercial stocks at ecologically sustainable levels, and within this context, maximise the economic returns to the Australian community” (DAFF, 2007). To meet this objective, harvest strategies are designed to pursue an exploitation rate that keeps fish stocks at a level required to produce maximum economic yield (MEY) and ensure stocks remain above a limit biomass level (BLIM) at least 90% of the time. Alternative reference points may be adopted for some stocks to better pursue the objective of maximising economic returns across the fishery as a whole (AFMA, 2017a).

The following summary of the HSF structure and processes is adapted from AFMA (2017a):

The HSF uses a three tier approach designed to apply different types of assessments and cater for different amount of data available for different stocks. The HSF adopts increased levels of precaution that correspond to increasing levels of uncertainty about stock status, in order to reduce the level of risk associated with uncertainty. Tier 1 represents the highest quality of information available (i.e. a robust integrated quantitative stock assessment).

Each Tier has its own harvest control rule (HCR) that is used to determine a recommended biological catch (RBC). The RBCs provide the best scientific advice on what the total fishing mortality (landings from all sectors plus discards) should be for each species/stock. For all Tier levels, once the RBC is determined from the results of the assessment and the application of the relevant HCR, a recommended total allowable catch (TAC) is calculated based on the TAC setting rules.

For Tier 1, the HCR is based on the following reference points:

- The limit biomass BLIM –The default BLIM proxy is B20 = 20% of the unfished spawning biomass;

- The BMSY – the default BMSY proxy is B40 = 40% of the unfished spawning biomass;

- The target biomass BTARG (MEY) – BTARG is generally equal to BMEY, for which the default proxy is approximated by 1.2*BMSY. If the default BMSY proxy is used, this results in B48 = 48% of the unfished spawning biomass.

The Tier 1 harvest control rule applies to species and/or stocks where there is a robust quantitative assessment that provides estimates of current biomass levels, and where estimates or appropriate proxies are available for BLIM, BTARG and FTARG.

Tier 3 and Tier 4 assessments use other indicators (relating to fishing mortality and catch rates respectively) and reference points which are taken as proxies for the biomass reference points for Tier 1.

A Tier 3 stock assessment uses information available on the age structure of annual catches and annual total catch weight, as well as knowledge of basic biological parameters, e.g. natural mortality, length at age, weight at length, the stock recruitment relationship steepness, fecundity at age and selectivity at age. The catch control rule uses the ratio of the target exploitation rate to the actual exploitation rate as a multiplier on the current average catch to determine the RBC.

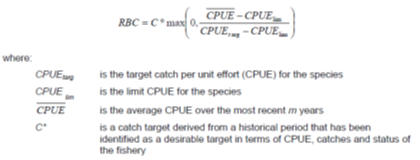

The Tier 4 assessment is based entirely on catch and CPUE. The Tier 4 analysis determines an RBC by selecting CPUE reference points that are taken as proxies for the estimated BLIM and BTARG. This is done by assuming that the CPUE is proportional to stock abundance, an assumption that is made in most SESSF assessments.

HCRs under each Tier of the HSF have been subject to robust simulation testing (e.g. Wayte, 2009) with results published in peer-reviewed journals (e.g. Little et al, 2011).

The status of fish stocks in the SESSF, and how they are tracking against the HSF, is reported to the relevant Resource Assessment Group (RAG), the relevant Management Advisory Committee (MAC) and AFMA Commission as part of the yearly TAC setting process. The data used for input into the stock assessment process are collected by the observer-based Integrated Scientific Monitoring Program (ISMP), AFMA logbooks and Catch Disposal Records (CDRs) and periodic trawl-based Fishery Independent Surveys (FIS). Otoliths from the biological sampling are provided to a private contractor for ageing. All sampling and age data are provided to stock assessment scientists for analysis or reporting. Stock assessment reports are produced by CSIRO or other contracted assessment specialists and discussed by the RAG. The outcomes of assessments are run against the HCRs in the HSF to produce recommended biological catch (RBC) amounts for each quota species. Other sources of mortality, including an estimate of future discards, catch taken by other jurisdictions (e.g. State and recreational sectors) and a research catch allowance, are subtracted from the RBC to produce a Commonwealth TAC.

Each stock is assessed under the appropriate Tier level as advised by the RAGs. In mid-December, AFMA produces a position paper with recommended TACs for quota species for the upcoming fishing season, based on the stock assessments and RAG advice. The paper is distributed to interested parties and undergoes a public comment period.

In early February, a South East Management Advisory Committee (SEMAC) TAC Setting meeting is held where TAC recommendations are made. The outcomes of RAGs and SEMAC together with the AFMA position paper and any public comments received, are then sent to the AFMA Commission to determine TACs for the upcoming fishing season in mid-February.

The southern Australia biological stock of N. gouldi is harvested by a range of fisheries including:

- The Commonwealth Southern Squid Jig Fishery (SSJF);

- The Commonwealth Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (SESSF) (Commonwealth Trawl Sector – CTS – and Great Australian Bight Trawl Sector – GABTS);

- The Tasmanian Scalefish Fishery (TSF); and

- Recreational fisheries.

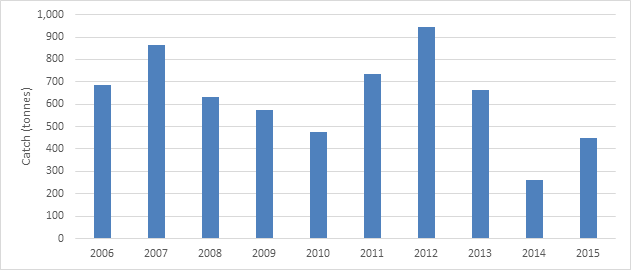

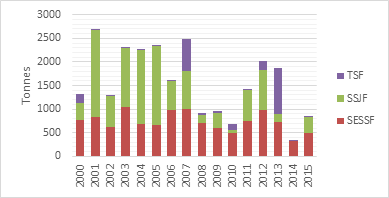

Catches in the two Commonwealth fisheries have historically dominated total landings, however substantial catches were taken in the TSF in 2012-13 (Figure 3). Recreational catches in Tasmania were estimated at 21t in 2012-13 (Noriega et al, 2016).

Figure 4: Australian Gould’s squid commercial catches between 2000 and 2015.

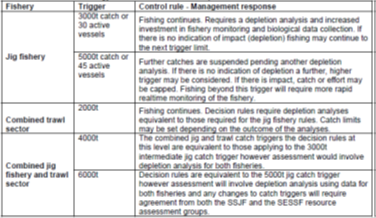

The SSJF and SESSF are subject to management arrangements specified in the Arrow (Gould’s) Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy. This harvest strategy details processes for monitoring and conducting assessments of the biological and economic conditions of the fishery. The harvest strategy covers the SSJF as well as sectors of the SESSF and other Commonwealth fisheries which may take Gould’s squid in the Australian Fishing Zone. The Arrow (Gould’s) Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy was implemented on 1 January 2008.

In the absence of biomass estimates, the harvest strategy uses suites of intermediate and limit catch and effort triggers based on recent catch history, with values well below historical high catch levels. A series of defined actions are associated with each trigger (e.g. re-assess the fishery using depletion analysis if a trigger of 5,000t from the SSJF or 6,000t overall is reached). These do not specify catch reductions (or increases) but are consistent with the existing lightly-exploited nature of the fishery (Anon, undated). Under the current SSJF Management Plan, advice will be provided by a Southern Squid Jig Fishery Resource Advisory Group (SquidRAG) on an appropriate management response, should any of the trigger catch levels be reached.

The TSF uses jigs and is subject to limited entry, vessel restrictions (<20m) and spatial and temporal closures. There were 12 active vessels in the TSF in 2015, and the number of automatic squid jigging licenses is limited to 7 in 2016-17 [1].

Notwithstanding larger catches in 2011-12 and 2012-13, catch remains well below historical levels. The harvest strategy in the Commonwealth sectors, which have dominated catches except for 2012-13, is responsive to the state of stock and the elements work together towards achieving the stock management objectives reflected in Criterion 1A(i). Catches in the TSF should continue to be monitored in the context of ensuring effective management arrangements across the full range of the stock.

[1] http://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/sea-fishing-aquaculture/commercial-fishing/scalefish-fishery/commercial-scalefish

| (b) Shark-finning |

|

|

NA

| CRITERIA (ii): There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place |

LOW RISK |

|

Well-defined HCRs are set out for each Tier 1-4 species covered by the SESSF HSF (AFMA, 2017a). HCRs are designed to achieve the objectives set out in the HSF which in turn has been designed to meet the Commonwealth HSP (DAFF, 2007).

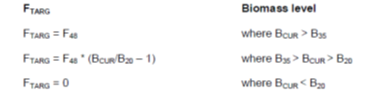

Under the HSF, for Tier 1 stocks the target fishing mortality rate FTARG represents the fishing mortality rate that would result in a spawning biomass of BTARG (equal to BMEY). The default value for FTARG is F48, the value of F corresponding to a BTARG of B48. Alternative reference points may be adopted for some stocks to better pursue the objective of maximising economic returns across the fishery as a whole. The recommended maximum fishing mortality rate for Tiers 3 and 4 is FMSY (the default proxy for which is F40). This represents the fishing mortality rate that would cause the spawning biomass to decline to its maximum sustainable biomass BMSY (the default proxy for which is B40). The breakpoint, or HCR inflection point, in the overfishing line occurs at a biomass corresponding to BMSY. If B<BMSY or F>FMSY, the TACs should be reduced to limit fishing effort and the fishing mortality rate. For Tier 1, the recommended maximum fishing mortality rate and HCR inflection point occurs at a proxy of F35.

Figure 8: Schematic representation of a harvest control rule, showing key reference points (Source: AFMA, 2017)

Recommended Biological Catch (RBC) is calculated according to the following (AFMA, 2017a):

Tier 1

The formula for calculating FTARG is as follows:

The RBC is calculated by applying FTARG to the current biomass BCUR to calculate the total catch (including discards) in the next year, using the agreed base case assessment model:

![]()

At Tier 1, BLIM = B20, the maximum value for FTARG = F48 and the breakpoint in the HCR occurs at B35. Alternative reference points may be adopted for some stocks to better pursue the objective of maximising economic returns across the fishery as a whole.

The HCRs are robust to the main uncertainties (SI(b)) as they have been developed over a period of time involving world leading scientists, underpinned by publications in peer-reviewed journals. There is substantial evidence that the HCRs have been successfully implemented across a diverse range of gear types and species of Commonwealth fisheries (SI(c)). Additional HCRs are also applied for specific fisheries or species where necessary, developed through the Resource Assessment Group, and applied and monitored by AFMA.

Tier 3

The Tier 3 HCR applies to species and/or stocks that do not have a quantitative stock assessment, but where estimates of fishing mortality and other biological information are available (AFMA, 2017a). Yield per recruit calculations are used to calculate F values that will reduce the spawning biomass to 20% (F20), 40% (F40) and 48% (F48) of the unexploited level.

Recommended biological catch CRBC is calculated according to the following formula:

where FCUR is the estimated current fishing mortality, and FRBC is the selected F for the recommended biological catch from the control rule. The estimate of fishing mortality is limited to be no less than 0.1 of natural mortality.

Tier 4

The Tier 4 control rule is of the form:

A range of considerations are then taken into account in translating the RBC into a TAC. For Tier 4 species a ‘discount factor’ of 15% is applied to account for greater levels of uncertainty in these stocks. Other sources of mortality including state catches, discards and any research catch allowance are then subtracted from the RBC to produce a Commonwealth TAC.

Multi-year TACs are to be applied for all Tier 1 and Tier 4 species where suitable. Where the RBC is zero, an incidental bycatch TAC may be set after considering a range of circumstances including the impact of incidental catches on rebuilding of the stock.

The Commonwealth Arrow (Gould’s) Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy uses a system of within-season monitoring against catch triggers for the jig and trawl sectors that signal the need for formal assessment. The main harvest strategy control rules are outlined in Table 2. Due to relatively low effort in the last few years, these triggers have far exceeded the catch and effort in the fishery.

Table 3: Harvest controls for the SSJF (Source: AFMA, 2009).

Although the Commonwealth HCRs do not apply to the TSF, given the historically low levels of catch and the greater potential for fishing effort in the Commonwealth sectors, these rules are likely to ensure that exploitation is reduced as the PRI is approached.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

1C: Information and Assessment

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy.

| (a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|

Comprehensive information on fleet composition, catch and other fishery-wide indicators is collected through the monitoring programs described in AFMA (2017). In 2016-17 fishing season there were 57 trawl vessels in the CTS, although only 34 were active (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a). Catch data are collected through compulsory logsheets and catch disposal records.

Notwithstanding difficulties in estimating biomass, sufficient information on stock structure, stock productivity and fleet composition are available to support the harvest strategy (see for example Jackson et al, 2003a,b; Virtue et al, 2011; Noriega et al, 2016; Emery and Bath, 2017, and references therein).

| (b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

LOW RISK |

|

Generic monitoring arrangements in place for the SESSF are described in the HSF (AFMA, 2017). These include:

Logbooks and catch records

AFMA requires fishers to record catch and effort information in logbooks at sea, and in catch disposal records (CDRs) which record the actual landed catch at port. CDRs are considered more accurate than logbook records. Data recorded for each fishing operation includes: the port and date of departure and return; gear type and fishing method; number of fish kept and discarded; and resultant catch and product form (e.g. trunked, gutted, filleted, whole).

The Integrated Scientific Monitoring Program (ISMP)

A key component of the ISMP is the sampling and recording of catches at ports and on board fishing vessels using fishery-independent observers. The purpose of the ISMP is to provide reliable, verified and accurate information on the fishing catch, effort and practice of a wide range of vessels operating inside and, periodically, outside the Australian Fishing Zone. Biological and environmental data are collected on: catch composition including size and weight; amount and type of incidental catch; number of fish kept and discarded; fate of target and non-target species; interactions with TEP species; and fishing effort.

Fishery Independent Surveys (FIS)

The FIS is an industry-based fishery-independent resource survey which provides a timeseries of relative abundance indices for key target species (e.g. Knuckey et al, 2015). A FIS has been conducted for key target species in the SESSF since 2008. Biological and environmental data are collected such as: target species; catch rate (kg/shot); fishing method; and fishing depth. Information which provides a relative abundance index of other main byproduct and incidental catch species is also obtained.

Stock abundance is monitored through models of varying sophistication based on data availability for Tier 1, 3 and 4 species. All UoA removals, including state catches and discards, are estimated in TAC decision making.

Accordingly, for all Tier 1-4 species stock abundance and UoA removals are regularly monitored at a level of accuracy and coverage consistent with the HCR and there is good information on all other removals from the stock.

Given the highly variable nature of the stock, the need for abundance monitoring and other assessments (e.g. depletion analysis) is determined by monitoring catch against trigger points in the Commonwealth Arrow (Gould’s) Squid Fishery Harvest Strategy. Where effort and catch remain at low levels, no specific abundance monitoring is required (other than nominal CPUE/catch). In Commonwealth fisheries, removals from the stock are monitored using daily catch and effort logbooks, catch disposal records and occasional observer coverage. Removals from the stock by the TSF are monitored through compulsory catch and effort logbooks. In the Commonwealth sector, monitoring arrangements are consistent with the HCR.

CRITERIA: (ii) There is an adequate assessment of the stock status.

| (a) Stock assessment |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

No formal stock assessment exists for this stock (Noriega et al, 2016). AFMA (2009) note that given the high natural variability of arrow squid, the standard stock assessment techniques used for fish such as teleosts or chondrichthyans are not appropriate. Current knowledge of the southern squid resource is insufficient to allow biomass or suitable proxies for reference points to be estimated. Nevertheless, Noriega et al (2016) and Emery and Bath (2017) use alternative empirical indicators including catch rates and total catch to estimate stock status using a weight of evidence approach. This approach estimates stock status relative to generic reference points appropriate to the species category.

| (b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

LOW RISK |

|

Stock assessments for all Commonwealth managed stocks are subject to peer review and judgement (i.e., ability to reject the assessment) in the relevant Resource Assessment Group (RAG) and the South East Management Advisory Committee (SEMAC).

The main uncertainties are taken into account in the weight of evidence approach used by Noriega et al (2016). Although not a formal assessment, their conclusions are subject to external assessment.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

2A: Other Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI.

| (a) Main other species stock status |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

The intent of this scoring issue is to examine the impact of the fishery on ‘main’ other species taken while harvesting the target species. ‘Main’ is defined as any species which comprises >5% of the total catch (retained species + discards) by weight in the UoA, or >2% if it is a ‘less resilient’ species. The aim is to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired and ensure that, for species below PRI, there are effective measures in place to ensure the fishery does not hinder recovery and rebuilding.

In this assessment, main other species are assessed as those species that —

- constitute > 5% of the catch (by weight) or constitute > 2% of the catch and are ‘less resilient’; or

- were assessed as at least precautionary high risk during the Level 3 SAFE ERA (Zhou et al. 2012).

Species that constitute >5%, and >2% of the catch

Six other species which account for > 5% of the catch (Blue Grenadier, Blue-eye Trevalla,,Orange Roughy, Pink Ling, Gemfish and Ocean Jackets) are assessed under Component 1 in the full assessment report. Observer data indicates that otter trawlers directly interact with 533 species, 360 of these are teleosts, 39 are skates/rays and 63 are sharks (Walker et al., 2006). However, the fishery regularly retains around 30 target species and over 100 byproduct species. Knuckey and Upston (2013) report that “varying, but significant, levels of the catch (up to 50% by weight of quota and non-quota species combined) are caught and discarded in the “market” fishery. Although some commercial species are discarded, most of the discards are comprised of small fish species with little or no commercial value”.

Average annual retained catch in the CTS (inclusive of the Danish seine sector) during the three year period between 2013 and 2015 was 10,604t, based on catch disposal records. Species accounting for >5% of the retained catch, and not assessed here as target species, include Tiger Flathead (24.1%) and Eastern School Whiting (6.3%). Others which account for >2% of the retained catch include Silver Warehou (4.4%) and Mirror Dory (2.5%), although neither of these are likely to be considered ‘less resilient’ and both have recently been classified as neither overfished, nor subject to overfishing (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a). Eastern School Whiting are caught almost entirely by the Danish Seine sector of the CTS and thus do not need to be assessed here. Accordingly, we have assessed Tiger Flathead as a main other species, noting that all other species have been assessed through the SESSF ERA process discussed below.

Flathead

For SESSF management purposes, ‘flathead’ refers to a group of at least eight flathead species consisting predominantly of tiger flathead (Platycephalus richardsoni), but sand flathead (P. bassensis), southern flathead (P. speculator), bluespot flathead (P. caeruleopunctatus) and gold-spot or toothy flathead (P. aurimaculatus) are also caught regularly. Tiger flathead remains the dominant species in the catch and is the only species assessed in stock assessments at this stage. Data from onboard observers support catch data and indicates that P. richardsoni comprises over 95% of the SESSF catch of flathead (Morison et al. 2013); the results of aproductivity-susceptibility analysis suggest that the productivity of Tiger Flathead is not significantly different to the other five species regularly encountered. It is therefore reasonable to assume they won’t be disproportionately impacted by stock management arrangements directed at tiger flathead.

The most recent assessment of flathead estimated spawning stock biomass in 2014 to be 11 572 t or 50 per cent of the unfished (1915) level (Day & Klaer, 2014). The spawning biomass that supports maximum sustainable yield of Tiger Flathead was estimated to be 32 per cent of the unfished biomass. The biological stock is not considered to be recruitment overfished (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a). The available evidence indicates that the stock is highly likely to be above PRI.

Species assessed as at least precautionary high risk during the Level 3 SAFE ERA (Zhou et al. 2012).

Seventeen species or species groups were assessed as at least precautionary high by Zhou et al. (2012). A subsequent analysis demonstrated that the SAFE assessment significantly overestimated the risk to Bight skate, with the risk reduced from Extreme High Risk to Medium risk following an improved, data-intensive methodology (Zhou et al. 2013). However, given that some uncertainty still remains on the stock status of 16 other species, the measures in place to ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery or rebuilding are considered here.

It is worth noting that this assessment evaluates ‘other species’ across the CTS as a whole. Future assessments may benefit from greater depth and spatial separation of other species to account for the differences in other species catch composition across different areas and depth zones in the fishery.

AFMA employs an Ecological Risk Assessment for the Effects of Fishing (ERAEF) process for each Commonwealth fishery to determine risks posed by fishing to individual species. These outcomes are used here as a proxy for status of main other species in relation to PRI. Under the assessment framework used for this risk assessment, where there is evidence that a species/stock may be below PRI, measures must in place that are expected to ensure that the UoA will not hinder recovery and rebuilding for the UoA to meet the medium risk SG.

The AFMA ERAEF is a four step process:

- Level 1 analysis (SICA – Scale Intensity Consequence Analysis)

- Level 2 analysis (PSA – Productivity Susceptibility Analysis)

- Level 2 analysis (Residual risk PSA)

- Level 3 analysis (SAFE – Sustainability Assessment for Fishing Effects)

The first SAFE assessment was conducted in 2007 (Zhou et al. 2007). From this and previous Level 1 and Level 2 analyses, a Level 2 Residual Risk Assessment (AFMA 2012a) was published. The ERM identified a priority list of species to be assessed by the fishery, defined as those that were precautionary high risk or greater from the Level 2 and Level 3 assessments. In 2012, an updated SAFE assessment was completed (Zhou et al. 2012) for the CTS that identified a suite of additional species, including main other species, as precautionary high risk or greater risk. In 2014, residual risk guidelines were applied to the outcomes of the 2012 SAFE assessment for all teleost and chondrichthyan species (AFMA, 2014b).

At the completion of this process, a final list of 9 non-ETP species were identified as priorities to be treated through the SESSF Ecological Risk Management (ERM) Strategy 2015 (AFMA, 2015c) (Table 4).

Table 4: Priority species for the CTS identified through the ERA process (AFMA, 2015c).

| Common name | Species name | Highest level of Assessment | Risk rating |

| Dipturus australis | Common Skate | Level 3 SAFE | Extreme High Risk |

| Squalus mitsukurii | Green-Eyed Dogfish | Level 3 SAFE | (Greeneye spurdog listed as Extreme High Risk) |

| Azygopus pinnifasciatus | Righteye Flounder | Level 3 SAFE | Precautionary Extreme High Risk |

| Dipturus canutus | Grey Skate | Level 3 SAFE | Precautionary Extreme High Risk |

| Urolophus sufflavus | Yellow-backed Stingaree | Level 3 SAFE | Precautionary Extreme High Risk |

| Hydrolagus lemurs | Bight Ghost Shark | Level 3 SAFE | High Risk |

| Trygonorrhina fasciata | Eastern Fiddler Ray | Level 3 SAFE | High risk |

| Centrophorus squamosus | Nilson’s Deepsea Dogfish | Level 3 SAFE | Precautionary High Risk |

| Ventrifossa nigrodorsalis | Rattail | Level 3 SAFE | Precautionary High Risk |

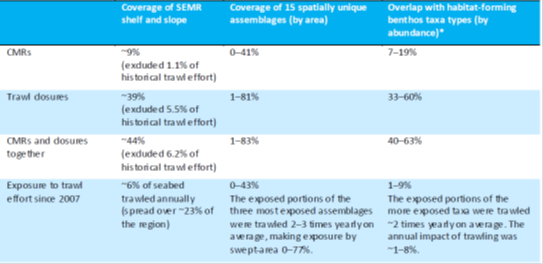

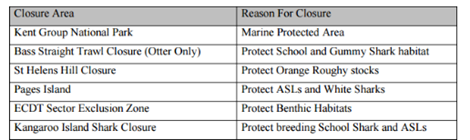

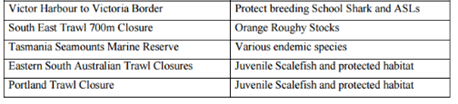

While there is uncertainty about the current status of the high-risk species in relation to PRI, the CTS has a number of measures in place to monitor, assess and manage impacts. These are outlined in the SESSF Ecological Risk Management (ERM) Strategy (AFMA, 2015c). These include:

- Overall effort limitations through TACCs on main target species (Pitcher et al [2015] estimated around 6% of the continental shelf and slope area in the South East Marine Region [SEMR] was exposed to trawl effort annually);

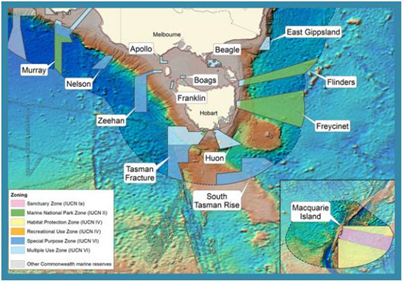

- Spatial closures through both fisheries and marine parks legislation – in 2007, a network of 13 marine protected areas was declared in the South-east marine region, with reserves that cover an area of 388,464 km2 across a depth range of 40m – 4600m;

- Species specific measures including:

- Upper-Slope Dogfish Management Strategy which includes:

- a prohibition on the take of Harrisson’s dogfish and southern dogfish (ETP species);

- area closures (see AFMA, 2012b, 2015c);

- monitoring obligations through observers or electronic monitoring;

- a limit for bycatch of Harrisson’s and southern dogfish when undertaking permitted types of line fishing in specific areas: and

- handling practices to improve post capture survival for released sharks.

- Shark and Ray Handling Practices: A Guide for Commercial Fishers in Australia – the shark handling guide was developed by AFMA to improve the handling of non-target shark species and to provide background material on fisheries related injuries and research on survivability.

- National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks

- Fishery-specific spatial closures – AFMA (2015c) list 5 fishery-specific area closures for dogfish, and a further 11 closures for protection of: school and gummy shark habitats and breeding stock, Orange Roughy stocks, white sharks, Australian Sea Lions, juvenile scalefish, various endemic species and important habitats; and

- Periodic ecological risk assessments of all non-quota species taken in the fishery

Accordingly, while there remains some uncertainty on the status of nine non-ETP species assessed as high risk or greater by AFMA (2014b) in relation to PRI, the fishery has measures in place that could be expected to ensure the UoAs do not hinder recovery and rebuilding if necessary. The strong recent history of the management agency in taking action to address known high risk areas (e.g. dogfish closures, nil TACs, etc) provides some confidence that the outcomes of the ERA process will be acted on. Further, ongoing improvements in the ERA methodology have resulted in the downgrading of risk ratings to at least some species (e.g. Bight skate) as more information is known, and application to other high risk species may produce similar results (Zhou et al, 2013). On this basis, the UoAs meet the medium risk SG.

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

AFMA has a comprehensive strategy in place to manage the impacts of the fishery on both target and non-target species.

The SESSF Management Plan 2003 sets out clear objectives for the management all species impacted by the fishery (i.e. that the fishery is “conducted in a manner consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development and the exercise of the precautionary principle and, in particular, the need to have regard to the impact of fishing activities on non-target species and the long-term sustainability of the marine environment”), as well as actions by which the objectives will be achieved. In relation to non-target species these include:

- Monitoring through a structured program, the impact of fishing on fish species, any other species that are caught as by-catch, ecologically-related species and the marine environment, analysing the impacts and implementing any strategies necessary to ensure: (i) the sustainability of those species and the marine environment; and (ii) that by-catch limitations are not exceeded;

- periodically checking the accuracy and consistency of information kept in relation to the fishery

For commercially-important species managed under quota, a HSF is applied which establishes evidence-based catch limits according to a clear framework of reference points and harvest controls rules (AFMA, 2017a). Evidence-based RBCs and TACs are set based of regular stock assessments, with additional precaution built into the TAC setting process for stocks for which information is limited. Flathead is managed as a Tier 1 species under the HSF. The strategy is expected to maintain the stock at levels which are highly likely to be above the PRI.

For all other species, AFMA assesses the potential impact of the fishery through the application of the ecological risk assessment process described under criterion 2A(i)(a) above. In addition, in the SESSF, the level 3 SAFE assessment was extended by Zhou et al. (2013) to provide a greater understanding of the cumulative risk posed by multiple fisheries accessing the same species. A Residual Risk Assessment was also undertaken on the Level 3 SAFE outcomes (AFMA, 2014b).

Species identified as high risk through the ERA process are subject to specific management measures to better understand or limit impacts under the SESSF ERM Strategy (AFMA, 2015c).

In the future, measures to manage impacts on non-target species will be guided by the AFMA Bycatch Strategy 2017-2022 (AFMA, 2017b).

Measures in place to monitor and manage impacts on non-target species in the CTS include:

- Limited entry;

- Catch controls through TACs and ITQs;

- Gear restrictions (e.g. >90mm single mesh twine);

- Bycatch reduction devices;

- Monitoring through logbooks and catch disposal records (CDRs);

- Monitoring through VMS;

- Observer coverage through the ISMP;

- Spatial closures; and

- Depth closures (although they are currently in review).

The harvest strategy framework, the ERA process, and the implementation of on-water actions through the SESSF ERM Strategy is likely to be considered as at least a partial strategy that is expected to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of the main other species at/to levels which are highly likely to be above the PRI.

| (b) Management strategy evaluation |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

For flathead, Tier 1 assessments estimating the stock to be above target levels provide an objective basis for confidence that the strategy in place will work.

For species identified as high risk through the ERA process, the SESSF ERM Strategy 2015 (AFMA 2015c) provides the framework for addressing impacts. These measures have been developed in consultation with SEMAC and other experts (e.g. CSIRO) as necessary. The measures are considered likely to work based on plausible argument, and therefore meet the medium risk SG, although for many there is yet to be an objective basis for confidence that the strategy will work and is being implemented successfully.

| (c) Shark-finning |

LOW RISK |

|

Shark finning at-sea is illegal in Commonwealth fisheries. All fisheries are subject to Fisheries Management Regulation 9ZO that makes it an offence for the caudal lobe, caudal fin, pectoral fin and dorsal fin to be removed from the shark at sea before it is in the possession of a fish receiver. Existing levels of observer coverage (129 days in 2016-17) and compliance monitoring is probably sufficient to verify the absence of shark finning to low risk levels.

| (a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|

The CTS is a multi-species fishery with numerous target species. AFMA’s ERA process, in addition to information provided through daily catch and effort logbooks, catch disposal records, protected species reporting, observer monitoring and VMS monitoring provides quantitative information to assess the UoA related mortality on other main species, and to support a management strategy. Observers collect detailed information on boat activity catch composition, as well as collection of data and samples for research programs and monitoring compliance of the boat with its fishing concession. Observer coverage rates are developed by AFMA in association with the RAGs. In 2016-17, observer coverage was 129 sea days, allocated across different geographical regions and times of the year (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a).

The risks that the otter trawl sub-fishery of the CTS poses to the sustainability of the marine ecosystem have been assessed through the application of a progression of risk assessment methodologies listed below:

- 2008 – ERA for effects of fishing completed to Level 2 Productivity Susceptibility Analysis (PSA) for non-teleost and non-chondrichthyans, habitats and communities, and to Level 3 Sustainability Assessment of Fishing Effects (SAFE) for all teleost and chondrichthyan species.

- 2010 – Application of residual risk guidelines to Level 2 PSA results for all non-teleost and non-chondrichthyan species.

- 2012 – Re-assessment by application of residual risk guidelines to Level 2 PSA results for non-teleost and non-chondrichthyan species; re-assessment of Level 3 SAFE for all teleost and chondrichthyan species.

- 2014 – Application of residual risk guidelines to Level 3 SAFE results for all teleost and chondrichthyan species.

Further information is available in the SESSF ERM Strategy (AFMA, 2015c).

Notwithstanding uncertainties around the population status of some high risk species, these monitoring programs provide qualitative and some quantitative information that is adequate in most cases to assess the impact of the UoAs on other species and to detect increases in risk. The main uncertainties, currently being addressed through the SESSF ERM Strategy, is the absence of information on some precautionary extreme high risk and high risk species. ecies.

PI SCORE – LOW RISK

2B: Endangered Threatened and/or Protected (ETP) Species

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species.

The UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

PRECAUTIONARY HIGH RISK |

|

At least 219 ETP species are thought to occur in the area of the CTS, including: three species of sharks, 74 species of seabirds, 51 species of marine mammals, 10 species of marine reptiles and 81 species of bony fish. (AFMA, 2015c). Protected species interactions are reported on the AFMA website: http://www.afma.gov.au/managing-our-fisheries/environment-and-sustainability/protected-species/.

For all ETP species, the risk that the fishery poses has been assessed through the application of the ecological risk assessment process described under criterion 2A(i)(a) above. Species identified through the ERA process as high risk are subject to specific risk treatment under SESSF ERM Strategy 2015 (AFMA, 2015c). These species are:

- Australian fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus);

- Albatrosses – multiple species

A further five species are listed as ‘conservation dependent’ under the EPBC Act and therefore could be considered ‘recognised’ under national environmental legislation (MSC, 2014). These include:

- Eastern Gemfish (Rexea solandri);

- Blue Warehou (Seriolella brama);

- Orange Roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus);

- School Shark (Galeorhinus galeus);

- Harrison’s Dogfish (Centrophorus harrisoni); and

- Southern Dogfish ( zeehaani).

Orange Roughy is assessed here as a target species and is not taken while targeting other species assessed here as target species. Accordingly, it is not considered further.

Pinnipeds (Low risk)

The areas fished by the SESSF overlap with the distributions of the Australian fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus), New Zealand fur seal (A. forsteri) and Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea). Fur seal populations have recovered substantially following heavy harvesting in the 18th and 19th centuries, with conservative best estimates of current abundance of 87,424 (S.E. 10,415) published in 2016 (Mackay et al. 2016). Australian sea lions are currently listed under the EPBC Act as vulnerable and there is a formal recovery strategy in place under the EPBC Act (DSEWPC, 2013). Only the Australian fur seal was identified as high risk from the CTS sector.

There is a potential for interactions with Australian fur seals (AFSs) in the CTS wet-boat sector (wet-boats being non-freezer operations) as identified by the ERA process. Early studies suggested that more than 700 seals may be caught annually in the wet-boat sector of the CTS (Stewardson and Aust. 2007). Helidoniotis et al (2017b) report that “in 2016, 136 pinniped interactions were reported in CTS and GHTS logbooks: 18 with Antarctic fur seals, 2 with Australian sea lions, 6 with New Zealand fur seals, 71 with Australian fur seals and 39 with seals of unknown species. This is a slight increase from the 134 interactions reported in 2015. Of the 136 reported pinniped interactions, 14 of the Antarctic fur seals, 1 Australian sea lion, 5 of the 6 New Zealand fur seals, 65 of the 71 Australian fur seals and 33 of the 39 unspecified seals were reported to be dead”. Of the interactions in the CTS in 2016, 89% were in the demersal trawl sector, with the remaining interactions in the Danish seine or mid-water trawl sectors.

Mackay et al. (2016) estimated Potential Biological Removal (PBR) which is, conceptually, the maximum number of anthropogenic mortalities a marine mammal population can sustain while still allowing that “stock” to reach or maintain its optimum sustainable population. The method is sensitive to a range of recovery factors (RF) with estimates of PBR ranging from 2,623 to 4,721 for RF values of 0.5 to 0.9, respectively. In other words, the population could sustain human induced mortalities of at least 2,600 seals annually with a high degree of confidence in this measure.

Koopman et al. (2014) examined the potential for the use of shortened cod-ends to reduce interactions. They report that “interactions with a total of 44 AFSs were recorded during the 1,117 fishing operations conducted by the Western Alliance during 14 February 2013 to 17 August 2014. This information is valuable as it the single-most long-term verifiable reporting of TEP interactions of a vessel in the CTS. Of the total of 44 AFSs, 9 were recorded as released alive, while 35 were dead”. Extrapolation of these figures to total trawl effort suggests that the annual level of seal interactions would be around 500. While this rate of interaction suggests there is a discrepancy with logbooks, the level of mortality is well below the estimated PBR for the species. Therefore, the direct effects of the fishery on the species are known and are highly likely to not hinder recovery of the species.

Cetaceans (Low risk)

In 2016, one interaction with a dolphin was reported in the CTS (Helidoniotis et al, 2017b). Dolphin mortalities are a rare event and this is verified by independent observers. Accordingly, it is highly likely the fishery is not preventing the population from recovering.

Seabirds (Medium risk)

For trawl fisheries, seabirds are vulnerable to injury as a result of striking the trawl warps during fishing operations, and this occurs predominantly when offal are being discarded (e.g. Favero et al. 2011). Phillips et al. (2010) analysed observer data from the CTS in 2006 which indicated that 31 shy albatross and 9 black-browed albatross were “captured” from 856 observed trawls. One of the limitations of assessing sea bird mortalities from warp strikes is that it is difficult to determine the proportion that survive. Phillips et al. (2010) chose to include all heavy interactions with the warp wire as “captures” even if the bird initially survived the interaction, due to uncertainty in post-interaction mortality, potentially resulting in over-estimation of the mortality rate. However, it was also noted that the observer data were not collected with the explicit aim of recording seabird interactions and thus some interactions were likely to have been missed. Phillips et al. (2010) concluded that “if the numbers observed in the 2006 calendar year are typical of other years, then reducing the seabird mortality in trawl fisheries (namely the CTS) should be a priority for the development of mitigation measures.”

Phillips et al. (2010) also highlighted a discrepancy between the reporting of seabird interactions in commercial logbooks compared to the rates reported by observers. This issue remains, with Helidoniotis et al (2017b) reporting that “seabird interactions are probably under-reported for numerous reasons, including that it may be difficult to constantly observe seabirds interacting with fishing gear and vessels, and that seabirds may not have visible injury after interactions such as warp strikes.”

In 2012, a Residual Risk Assessment of the Level 2 ERA was conducted (AFMA 2012a) that included assessments for seabirds. The two species assessed by Phillips et al. (2010), shy albatross and black-browed albatross, were both assessed as medium risk. Several other albatross species were identified as high risk from the initial PSA and were reduced to medium risk in the residual risk assessment taking into account the impacts of management measures introduced for these species. The group “Albatrosses – species unidentified” was assessed as high risk after the PSA and remained high risk after the residual risk assessment. The justification for retaining the high risk was “Twelve Albatrosses (species unidentified) were caught or interacted with in 2010 and 16 in 2011; all except one animal were deceased. It has been considered that it is a TEP species and the number of interactions that have occurred and no guidelines were applied which means the risk rating remains the same.” Thus, the key outcome from the Level 2 Risk Assessment was that the group of ‘unidentified albatrosses’ were the only high risk category. It should be noted that this analysis did not include the new gear technologies that significantly reduce the probability of interaction.

Since 2010, AFMA and SETFIA have led several research projects on various approaches to mitigate the impact on seabird populations, and in the last two years several new devices have significantly and sequentially reduced the level of seabird interactions. In 2017, two new technologies (water sprayers and bird bafflers) have been legislated that are expected to result in >90% reductions in seabird interactions (and by extension mortality). Given that the only high risk species are the “unknown” group, the issue remains one of a lack of information rather than known risks to these species. In the absence of this information, at this time it cannot be argued that the fishery is highly likely to not hinder recovery of all the albatross species. However, given the low numbers of annual mortalities in the unknown category, and the recently improved gear technologies that have been and are about to be implemented, there is a plausible argument that the CTS is likely to not hinder recovery of these unknown species and thus this SI is assessed as medium risk.

Upper-slope Dogfishes (Gulper sharks) (Medium risk)

Upper-slope dogfish (or ‘gulper sharks’) were targeted in the SESSF, GABTF and NSW trawl fisheries in the 1980s and 1990s and this resulted in the stocks being substantially depleted. Targeted fishing appeared to have effectively ceased in 2002 due to declining catch rates (Wilson et al. 2009), but very small quantities are still taken as byproduct (within trip limits).

Given the depleted state of the species (estimated to be <5–10 per cent of unfished levels on the upper slope off New South Wales, and unknown in other areas) the level of fishing mortality was considered too high to enable rebuilding, and three species of upper-slope gulper sharks (Harrison’s, Southern and Endeavour dogfish) were nominated for listing under the EPBC Act in 2008. The Endeavour Dogfish was found to be ineligible for listing in 2011 however, in 2013, Harrison’s and Southern Dogfish were listed as ‘conservation dependent’ after meeting the eligibility criterion for the ‘endangered’ listing. A rebuilding strategy is a requirement of the listing.

The Upper Slope Dogfish Management Strategy 2012 forms the basis of the rebuilding strategy and is designed specifically to rebuild the populations of Harrisson’s Dogfish and Southern Dogfish above a limit reference point (BLIM) of B25 (25% of unfished biomass) (AFMA, 2012b). The recovery time to B25 is estimated at around 86 years for Harrisson’s Dogfish, and 62 years for Southern Dogfish. The Strategy relies on a new network of spatial closures supplemented by a range of operational measures including regulated handling practices, 100% monitoring, move-on provisions and no retention of gulper sharks. The new closure network will provide protection, across the depth range, of 25% of the carrying capacity weighted core habitat of the continental slope stock of Harrisson’s Dogfish, 16.2% of the east stock of Southern Dogfish and 24.3% of the central stock of Southern Dogfish, in AFMA-managed waters. This closure network also protects 25% for Harrisson’s Dogfish, 25.9% for eastern Southern Dogfish, and 20.1% for central Southern Dogfish of core habitat area. The development of the strategy was supported by an Upper-Slope Dogfish Scientific Working Group which provided expert scientific advice on specific scientific questions to inform management and recovery of upper-slope dogfish species, as well as the normal AFMA consultative structure.

Despite gulper sharks being a no-take multispecies stock under the Strategy, reported landings for the trawl fishery were 0.3 t in the 2016–17 season (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a). Helidoniotis et al (2017a) suggest that this may reflect reporting errors. Nevertheless, they also note that “there is potential for unreported or underestimated discards, based on the large degree of overlap of current fishing effort with the core range of the species. Low levels of mortality can pose a risk for such depleted populations”.

The analysis undertaken during the development of the strategy provides some objective basis that the measures will work, although it is not clear at this point that the measures are being implemented successfully (there is no evidence yet of recovery) and there remains uncertainty over whether overfishing is occurring (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a). Accordingly, this SI is scored medium risk.

School shark (Medium risk)

While the school shark stock is overfished, catch from the otter trawl fishery is not likely to hinder recovery of the species. School shark catch from the otter trawl sub-fishery was 16 t on average for the last 3 years. This is less than 10% of the total catch of the species in the south east. Mortality from the UoA is considered within the Rebuilding Strategy, and current total commercial fishing mortality is within the limits set by the revised Strategy (AFMA 2014c).

Syngnathids (Low risk)

Syngnathids are taken as bycatch in the CTS in otter-trawl and Danish-seine nets but they are generally small and difficult to observe among large catches of fish. The ERAEF noted that 61 syngnathids have the potential to interact with the fishery and of these, only one was classified as high risk. However, when these risks were elevated to the Level 3 SAFE assessment conducted by Zhou et al. (2012), there were no syngnathids identified as high risk. On the basis of this outcome, it is expected that impacts on syngnathids are known and direct effects of the fishery are highly unlikely to hinder recovery.

Blue Warehou (Medium risk)

Blue Warehou has been classified as overfished since 1999 (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a). In February 2015, the species was listed as conservation dependent under the EPBC Act 1999. Two stocks of Blue Warehou exist: eastern and western. The stocks are managed under the SESSF tier 4 HSF and assessed using standardised CPUE to determine RBCs.

The 2008 rebuilding strategy for Blue Warehou was revised in 2014 (2014d) with the aim to prevent targeted fishing for Blue Warehou, minimise incidental catches and improve knowledge of stock status. The objective of the strategy is to rebuild the stock to its limit reference point (B20) by no later than 2024, and from there ultimately to the BMEY-based target reference point of B48. The strategy sets the targeted TAC at zero and allows for a limited bycatch TAC to cover incidental catches. The incidental TAC is currently set at 118t, consistent with CSIRO analysis of ‘unavoidable’ catch in 2010 (ShelfRAG, 2015). In the context of this SI, the incidental catch limit could be considered a ‘national limit’. The landed catch for 2016–17 was 16 t, and the weighted average discards were 8.68 t. The catch and discards combined was 24.68 t.

ShelfRAG (2015) examined progress towards achieving the objectives of the rebuilding strategy in 2015. They noted that catches have been small and over the last few years and below the incidental TAC, although as a consequence of low catches there are little data with which to assess recovery. They also noted that the number of shots containing more than 250 kg of Blue Warehou had declined over the previous 10 years with the most recent year being the lowest on record, catches of Blue Warehou by the top 10 boats had declined from 116 tonnes to less than two tonnes, and there was some evidence of range contraction.

Using projections from the Tier 1 stock assessment for the western stock, Haddon (2015; in ShelfRAG, 2015) projected that under recent catch conditions and using the highest average observed recruitment the stock should have rebuilt to 80% of the its original biomass; under average recruitment observed between 1987 and 2005 the stock should be at B38; and under the lowest average recruitment the stock should be at B20. On that basis, he concluded that the failure of the stock to recover seems unlikely to be due to excessive current incidental catches. A change in recruitment success could offer an explanation for the lack of observed rebuilding, as could a change in reproductive productivity although there is no mechanism to evaluate if this is the case (ShelfRAG, 2015).

Based on the available evidence, ShelfRAG (2015) concluded that current catches, even with low recruitment, should not be impeding recovery and catches would have to be substantially underestimated to have any effect.

Although level of fishing mortality that will allow the stock to rebuild is uncertain

, recent catches in the CTS are estimated to have been substantially below the incidental catch limit, modelling suggests the failure of the stock to recover is unlikely to be due to excessive incidental catches and the relevant RAG has concluded that current catches should not be impeding recovery. On that basis, there is a plausible argument that the known direct effects of the CTS are unlikely to be hindering recovery consistent with the medium risk SG. Nevertheless, the fishery would be better placed against this SI with some evidence of actual recovery.

Eastern Gemfish (Precautionary high risk)

Note: Because it is both a target species and an ETP species, Eastern Gemfish is assessed in Component 1 and here in Component 2 (i.e. Eastern Gemfish would be considered an ETP species for UoAs in which Eastern Gemfish is taken incidentally while targeting other species).

Eastern Gemfish is currently assessed as overfished. The integrated stock assessment model for Eastern Gemfish was last updated in 2010 with data on catch and length frequency up to 2009 (Little & Rowling 2010). The 2010 estimate of spawning stock biomass in 2009 was 15.6 per cent of the 1968 level.

The 2010 assessment included projections of Eastern Gemfish biomass based on average historical recruitment that examined two catch scenarios: total catches of 100 t each year and zero catches each year. The projection for zero catch indicated that the point estimate of biomass might reach 0.2SB before 2020. Projections for annual catches of 100 t suggested recovery to 0.2SB by 2025 (Morison et al, 2012). A full assessment has not been completed since 2010 due to a paucity of useful additional datasets. Nevertheless, an assessment of spawning potential ratio (SPR) was conducted to examine whether current levels of fishing represented overfishing of the stock (Little, 2011; in AFMA, 2015a). The SPR analysis showed that the ratio was high until the late 1970s when there were high recruitments and spawning biomass; SPR decreased starting in the mid-late 1970s reaching the lowest point in 1988 corresponding to high catches and thereafter has increased to earlier levels.

A stock recovery plan is in place with an incidental TAC of 100 t that aims to prevent targeting and promote recovery of the stock to a level above the limit reference point by 2027 (AFMA, 2015a). In the context of this SI, the 100t incidental TAC could be considered to be a national limit.

Although discards were high in 2013, and meant total fishing mortality (retained catch plus discards) was around double the incidental TAC, SERAG (2016) reports that total fishing mortality in Commonwealth fisheries was below the incidental TAC in 2012, 2014 and 2015. Moreover, Helidoniotis et al (2017a) report that the total fishing mortality in the 2016-17 fishing year was below the incidental TAC (77.4t in total).

While total mortality from the CTS has been below the incidental catch limit in most of the past five years, the main uncertainty is the extent to which existing catches may be hindering recovery under the low recruitment conditions experienced over recent years. Morison et al (2012) noted that stock recovery projections predicting the stock would recover to BLIM by 2025 depend strongly on average recruitment (also acknowledged in the rebuilding plan; AFMA, 2015a). However, Little and Rowling (2010) estimated that most of the recruitments during the last 25 years have been relatively weak. On that basis, while current catches in the CTS could be expected to not hinder recovery under average recruitment conditions, the extent to which they may hinder recovery under low recruitment conditions is unclear. Accordingly, we have scored this SI precautionary high risk.

Other listed species

Sharks (Low risk)

A number of other shark species are listed on international conventions to which Australia is a member and are therefore recognised under the EPBC Act. These include Longfin Mako (Isurus paucus), Shortfin Mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) and Porbeagle (Lamna nasus) sharks – listed on the EPBC Act in January 2010 after their inclusion on Appendix ii of the Convention of Migratory Species (CMS) – and Scalloped Hammerhead Shark (Sphyrna lewini), Great Hammerhead Shark (Sphyrna mokarran), Smooth Hammerhead Shark (Sphyrna zygaena) and Oceanic Whitetip Shark (Carcharhinus longimanus), included on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in September 2014. Porbeagle sharks were also included on CITES Appendix II at the same time.

Catches of each of these species is small or non-existent in the CTS. An average of 1.9t of retained catch of Shortfin Mako was reported during 2013 to 2015. Relative to catches in other fisheries (Clarke, 2011, notes that median estimates by number of mako sharks recorded by observers in South Pacific longline fisheries were between 50,000-250,000 individuals in 2006), it is highly unlikely that the marginal impact of catches in the CTS are hindering recovery. Of the remaining species, an average of 68kg of Smooth Hammerhead Shark was retained between 2013 and 2015, 32kg of Porbeagle was retained in 2014 and no retained catches of the other species were reported.

Scoring

Of the ETP species assessed above, the eastern stock of Gemfish received the highest risk rating of precautionary high risk. Target species UoAs likely to interact with this stock are therefore scored precautionary high risk and include: Blue Grenadier, Blue-eye Trevalla, the Pink Ling – eastern stock, Gould’s Squid and Ocean Jacket. The remaining stocks are scored medium risk.

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

- meet national and international requirements; and

- ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery of ETP species.

| (a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

AFMA has a comprehensive framework of measures in place to manage the impacts of the fishery on ETP species.

The SESSF Management Plan 2003 sets out clear objectives for the management all species impacted by the fishery (i.e. that the fishery is “conducted in a manner consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development and the exercise of the precautionary principle and, in particular, the need to have regard to the impact of fishing activities on non-target species and the long-term sustainability of the marine environment”), as well as actions by which the objectives will be achieved. In relation to non-target species these include:

- Monitoring through a structured program, the impact of fishing on fish species, any other species that are caught as by-catch, ecologically-related species and the marine environment, analysing the impacts and implementing any strategies necessary to ensure: (i) the sustainability of those species and the marine environment; and (ii) that by-catch limitations are not exceeded;

- periodically checking the accuracy and consistency of information kept in relation to the fishery

The impacts of the fishery on all ETP species in the fishery area have been assessed through the ERA framework described in 2A(i). For those species identified as high risk, measures to mitigate risks are set out in the SESSF ERM Strategy (AFMA, 2015c). Key measures in place which serve to mitigate risks include:

- Limited entry;

- Catch controls (e.g. zero targeted TACs and incidental catch trip limits);

- Gear modifications such seal excluder devices (SEDs) and bird scaring devices;

- Extensive spatial closures under fisheries legislation (e.g. deepwater shark closures);

- Extensive spatial closures to trawling under the South East Marine Protected Area network (388,464 km2 with a depth range of 40m – 4600m).

All interactions with ETP species are required to be reported in compulsory logbooks. Interactions are also reported by observers under the ISMP.

- In addition to the measures above, a framework of species

-specific conservation measures apply. These include:

‘Conservation dependent’ species

Fishing restrictions have been imposed on all overfished stocks listed under the EPBC Act as ‘conservation dependent’. These restrictions are to promote the rebuilding of the stock to a level above the target reference limit within an allocated timeframe. AFMA develops stock rebuilding strategies in consultation with the fishing industry, the Department of the Environment, the Department of Agriculture and the relevant management advisory committee and resource assessment group.

Rebuilding strategies are reviewed every five years to monitor the progress of rebuilding and ensure the continued effectiveness of management arrangements which have been implemented.

Specific management plans have been compiled for the following ETP species[1]:

- School shark Rebuilding Strategy 2015

- Orange Roughy Rebuilding Strategy 2014

- Upper Slope Dogfish Strategy 2012

- Eastern Gemfish Rebuilding Strategy 2015

- Blue Warehou Rebuilding Strategy 2014

These instruments are likely to be considered a strategy that is expected to ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery. The main uncertainty for several species is the extent to which measurable recovery has occurred (e.g. Eastern Gemfish, Blue Warehou), and the extent to which recovery will occur under recent recruitment conditions.

Pinnipeds

SEDs have been compulsory for freezer boats in this component of the SESSF since 2005, and modifications to fishing practices seem to have substantially reduced the incidence of seal bycatch in the midwater nets of factory vessels (Helidoniotis et al, 2017b). Trials of SEDs in the wet-boat sector have achieved positive results (Knuckey, 2009), and industry has adopted a code of conduct that includes voluntary measures to minimize interactions. Seal bycatch (alive or dead) must be formally reported to SEWPaC and AFMA within 24 hours of the time of capture. Helidoniotis et al (2017b) report that “trials of a flexible SED design suitable for use in smaller nets have been reasonably successful (Knuckey, 2009), but reliably estimating and reducing the level of interactions between seals and wet-boats remain difficult. A trial using a shortened codend to reduce seal bycatch was completed in late 2014. The trial found no definitive proof that short trawl nets had lower interaction rates with seals, caught fewer seals or resulted in lower mortality rates of caught seals (Koopman et al. 2014).” Historically, there have been concerns about under-reporting of pinniped interactions.

The framework of measures in place through the SESSF Management Plan, ERA/ERM processes, independent monitoring through observers, targeted research and species specific measures to limit interactions (e.g. SEDs) are likely to be considered a strategy that is expected to ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery for high risk pinnipeds.

Seabirds

In response to the detection of seabird interactions with trawl gear in the SET and GAB sectors of the SESSF, AFMA has worked in conjunction with industry and seabird experts to develop and implement Seabird Management Plans (SMPs) on all SESSF otter board trawl vessels (Helidoniotis et al, 2017b). Seabird management plans were introduced in the CTS in 2011.

Seabird management plans are tailored to individual fishing boats and identify the main threats posed to seabirds by that boat. Each plan identifies the physical mitigation measures to stop seabirds from interacting with the warp wires and other fishing gear. They also include measures dealing with the discharge of biological waste from vessels to reduce seabird attraction and interaction. Further ‘common-sense’ measures are employed by fishers to help reduce the risk of interactions, including reducing the time the nets are on the surface of the water and cleaning the net of fish when re-setting. This reduces the likelihood of seabirds using the nets as a food source and consequently getting entangled. Seabird Management Plans set out a variety of proven mitigation measures that are tailored to each vessel in each fishery. Trawl fishers must use ‘warp deflectors’ or pinkie devices. These are pink buoys that sit alongside the trawl gear as a visual deterrent. The buoys also act as a physical barrier between birds and fishing gear.

Recently, the South East Trawl Fishing Industry Association (SETFIA) led a research project to trial other alternative seabird mitigation devices, which resulted in sea trials for two new devices: water sprayers and bird bafflers (Boag, 2016). Sprayers were found to reduce interactions by 92% while bafflers reduced interactions by 96%. AFMA have approved both approaches for use as seabird mitigation devices within vessels’ seabird management plan (as a condition on the fishing permit). From 1 May 2017, all CTS trawl vessels must use one of these two devices or continue with pinkies and not discharge offal while towing. As it is not economical to retain offal, it is probably reasonable to assume that from May 2017, uptake of the new devices is likely to be high. SETFIA have also recently introduced a Code of Conduct and an E-Learning programme to attempt to improve seabird avoidance measures and seabird interaction reporting.

CTS vessels are also subject to the measures in the National Recovery Plan for Threatened Albatrosses and Giant Petrels 2011-2016 (DSEWPC, 2011).

The framework of measures in place through the SESSF Management Plan, ERA/ERM processes, independent monitoring through observers, targeted research and species specific measures to limit interactions (e.g. seabird mitigation devices) are likely to be considered a strategy that is expected to ensure the UoA does not hinder recovery for seabirds

[1] http://www.afma.gov.au/sustainability-environment/protected-species-management-strategies/

| (b) Management strategy implementation |

MEDIUM RISK |

There is an objective basis for confidence for some species groups (e.g. mitigation approaches for seals and seabirds have followed international best practice approaches) that the management measures are likely to work, however in the case of Eastern Gemfish, Blue Warehou and Upper Slope Dogfish there is currently insufficient evidence to suggest that the strategy is being implemented successfully. As such this SI is assessed as medium risk on the basis that a plausible argument exists that the measures are likely to work.

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

- information for the development of the management strategy;

- information to assess the effectiveness of the

- management strategy; and

- information to determine the outcome status of ETP species.

| (a) Information |

MEDIUM RISK |

|

A range of quantitative and qualitative information is available on ETP interactions which has been adequate to assess UoA related mortality for most species.

The primary sources of information on ETP species interactions include compulsory commercial fisher reporting in logbooks, observer coverage through the ISMP and targeted studies on specific species (e.g. school sharks, upper slope dogfishes, Australian fur seals). Catch and effort information is also available for commercially important ‘conservation dependent’ listed species (e.g. Eastern Gemfish, Blue Warehou, gulper sharks).

To assist fishers accurately identify protected species, AFMA has produced the following guides:

- Protected species identification guide

- Shark and Ray eBook

- Seabird identity guide

A summary of interactions with commonwealth fisheries is available online at:

http://www.afma.gov.au/environment/eco_based/reporting.htm#reports.

In 2016-17, observer coverage was 129 sea days, allocated across different geographical regions and times of the year (Helidoniotis et al, 2017a). Although the ISMP was not developed to evaluate ETP species interaction, ISMP data has been used to validate logbook data. Onboard cameras are being trialled in some SESSF fisheries as a way of monitoring bycatch of ETP species and may be used to gather information; however this work is subject to further trials.

- Information available on the distribution of ETP species within the fishery area, together with information on their biological characteristics and rates of interaction

- through logbooks and

- the ISMP, has allowed an assessment of the

likely impacts on ETP species through ecological risk assessments

described in PI 2A (e.g. AFMA, 2012a).

For several ETP species,