South Australian Sardine Fishery

Assessment Summary

|

South Australian Sardine |

||

|

Product Name: |

Australian Sardine |

|

|

Species: |

Australian Sardine (37 085002), Sardinops sagax (Jenyns, 1842) |

|

|

Southern Australia |

||

|

Gear type: |

Purse seine |

|

|

Year of Assessment: |

2017 |

|

Adapted from the Sardine Management Plan, PIRSA (2014a), and the latest stock assessment report (Ward et al 2015a).

The South Australian Sardine Fishery (SASF) is primarily based on the capture of Australian Sardine (Sardinops sagax) using a sardine net (Australian Anchovy (Engraulis australis) is also permitted). Access to the Australian Sardine Fishery is provided through a licence for the Marine Scalefish Fishery (MSF) with a sardine net endorsement, which allows the licence holder to use a small-mesh (14-22 mm) purse seine net when fishing for marine scalefish.

The fishery is managed through an individual transferrable quota (ITQ) system with a total allowable commercial catch (TACC) set for each 12-month period. Under the current arrangements, the TACC is divided equally between the licence holders, and the quota period commences on 1 January of each year. Since 2010, spatial management zones have been used to encourage the development of the fishery outside of Spencer Gulf and Gulf St Vincent. The TACC from 2010 to 2014 was 34,000 t, while the TACC for 2015 was 38,000 t. The fishery has complementary input controls including limited entry and gear restrictions.

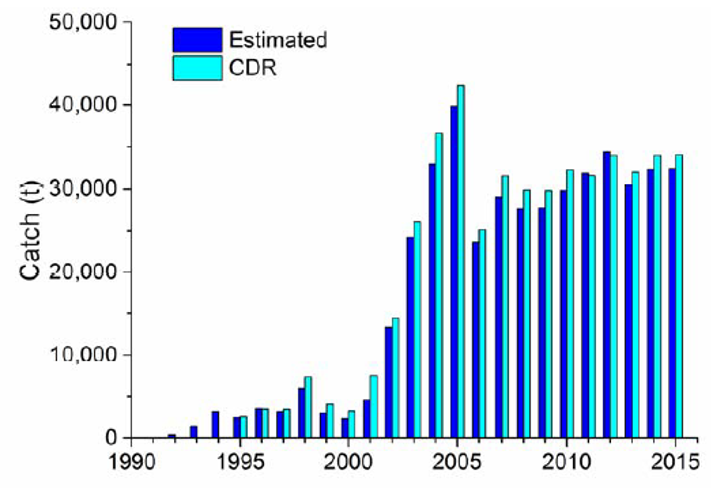

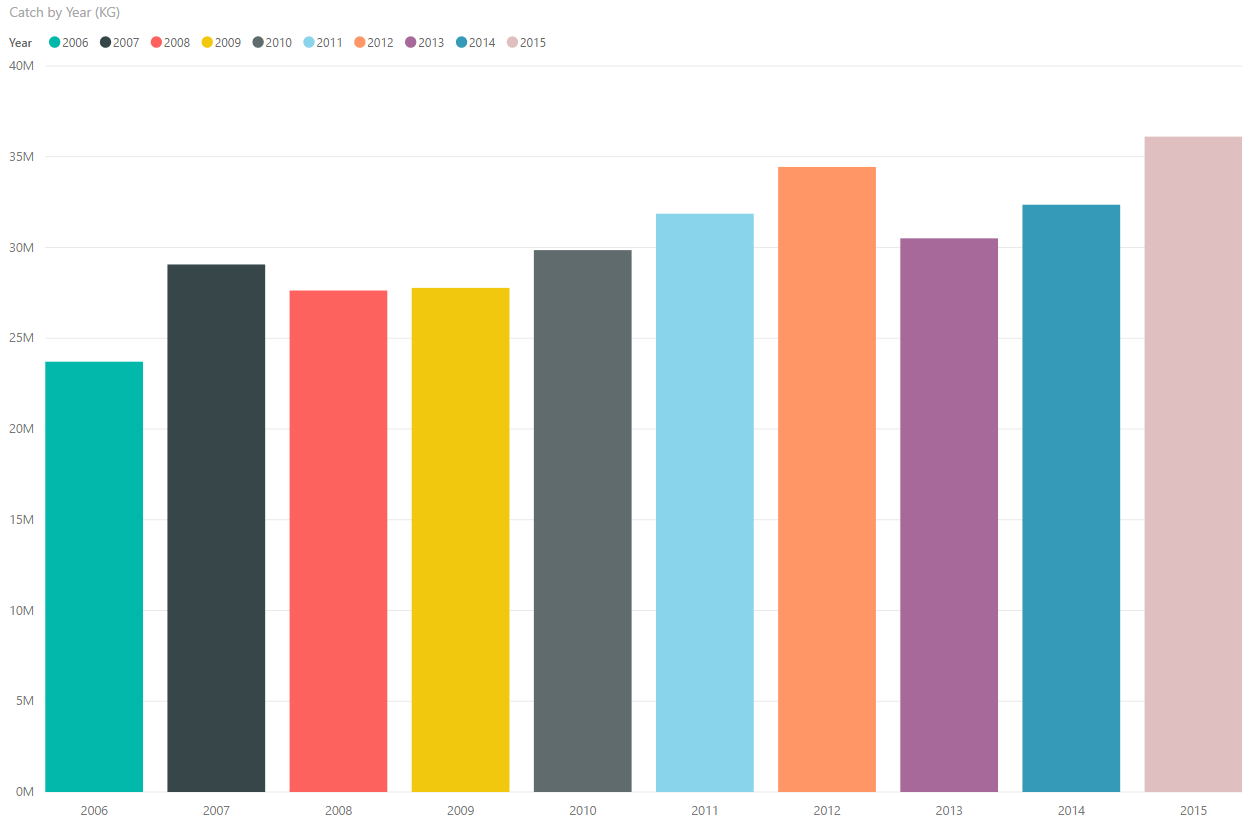

Total annual catches rose from 7 t in 1991 to reach 42,475 t in 2005, before stabilising at ~30,000 t in 2007-2009 (Figure 1). During 2010-14, the catch ranged between 32,262 t and 33,972 t. Annual effort peaked at 1,274 net-sets in 2005 and remained stable at 760-1077 net-sets between 2007 and 2014. Effort and catches usually peak in March-June.

Figure 1: Total catches (logbooks, CDR) for the South Australian Sardine Fishery (Source Ward et al, 2015a).

The first management plan for the fishery, ‘A Management Plan for the Experimental Pilchard Fishery’, was developed in 1995 and set out the objectives for management of the fishery, management arrangements, and the primary indicators for assessing the fishery. A decade later the ‘Management Plan for the South Australian Pilchard Fishery’ was released which included the first harvest strategy.

|

Performance Indicator |

Score |

|

COMPONENT 1 |

LOW RISK |

|

1A: Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

|

1C: Information and Assessment |

LOW RISK |

|

COMPONENT 2 |

LOW RISK |

|

2A: Other Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2B: ETP Species |

LOW RISK |

|

2C: Habitats |

LOW RISK |

|

2D: Ecosystems |

LOW RISK |

|

COMPONENT 3 |

LOW RISK |

|

3A: Governance and Policy |

LOW RISK |

|

3B: Fishery-specific Management System |

LOW RISK |

- The stock is assessed using biennial Daily Egg Production Method surveys. The most recent estimates of spawning biomass have been above 150,000 t, which is well above the limit reference point of 75,000 t identified in the management plan for the fishery (Ward et al 2016a).

- The current exploitation rate is around 23 per cent, which is well below the level considered safe for this species (33 per cent) taking into account its role in the ecosystem.

- The fishery is well placed against bycatch and ecosystem performance indicators. Interactions with common dolphins are monitored by independent observers and managed through an industry code of practice.

|

Component |

Outlook |

Comments |

|

Target fish stocks |

Stable |

Spawning biomass has been maintained above target levels for the majority of the last decade. |

|

Environmental impact of fishing |

Stable |

Ecosystem impacts are well understood, which is important given Australian Sardine is a low trophic level species. No major changes are expected to Component 2 PIs. |

|

Stable |

No major changes are expected to Component 3 PIs. |

This report sets out the results of an assessment against a seafood risk assessment procedure, originally developed for Coles Supermarkets Australia by MRAG Asia Pacific. The aim of the procedure is to allow for the rapid screening of uncertified source fisheries to identify major sustainability problems, and to assist seafood buyers in procuring seafood from fisheries that are relatively well-managed and have lower relative risk to the aquatic environment. While it is based on the GSSI Benchmarked MSC Standard version 2.0, the framework is not a duplicate of it nor a substitute for it. The methodology used to apply the framework differs substantially from an MSC Certification. Consequently, any claim made about the rating of the fishery based on this assessment should not make any reference to the MSC or any other third party scheme.

This report is a “live” document that will be reviewed and updated on an annual basis.

Detailed methodology for the risk assessment procedure is found in MRAG AP (2015). The following provides a brief summary of the method as it relates to the information provided in this report.

Assessments are undertaken according to a ‘unit of assessment’ (UoA). The UoA is a combination of three main components: (i) the target species and stock; (ii) the gear type used by the fishery; and (iii) the management system under which the UoA operates.

Each UoA is assessed against three components, consistent with the MSC principles:

- Target fish stocks;

- Environmental impact of fishing; and

- Management system.

Each component has a number of performance indicators (PIs). In turn, each PI has associated criteria, scoring issues (SIs) and scoring guideposts (SGs). For each UoA, each PI is assigned one of the following scores, according to how well the fishery performs against the SGs:

- Low risk;

- Medium risk;

- Precautionary high risk; or

- High risk

Scores at the PI level are determined by the aggregate of the SI scores. For example, if there are five SIs in a PI and three of them are scored low risk with two medium risk, the overall PI score is low risk. If three are medium risk and two are low risk, the overall PI score is medium risk. If there are an equal number of low risk and medium risk SI scores, the PI is scored medium risk. If any SI scores precautionary high risk, the PI scores precautionary high risk. If any SI scores high risk, the PI scores high risk.

For this assessment, each component has also been given an overall risk score based on the scores of the PIs. Overall risk scores are either low, medium or high. The overall component risk score is low where the majority of PI risk scores are low. The overall risk score is high where any one PI is scored high risk, or two or more PIs score precautionary high risk. The overall risk score is medium for all other combinations (e.g. equal number of medium/low risk PI scores; majority medium PI scores; one PHR score, others low/medium).

For each UoA, an assessment of the future ‘outlook’ is provided against each component. Assessments are essentially a qualitative judgement of the assessor based on the likely future performance of the fishery against the relevant risk assessment criteria over the short to medium term (0-3 years). Assessments are based on the available information for the UoA and take into account any known management changes.

Outlook scores are provided for information only and do not influence current or future risk scoring.

Table 1: Outlook scoring categories.

|

Outlook score |

Guidance |

|

Improving |

The performance of the UoA is expected to improve against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

|

Stable |

The performance of the UoA is expected to remain generally stable against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

|

Uncertain |

The likely performance of the UoA against the relevant risk assessment criteria is uncertain. |

|

Declining |

The performance of the UoA is expected to decline against the relevant risk assessment criteria. |

Information to support scoring is obtained from publicly available sources, unless otherwise specified. Scores will be assigned on the basis of the objective evidence available to the assessor. A brief justification is provided to accompany the score for each PI.

Assessors will gather publicly available information as necessary to complete or update a PI. Information sources may include information gathered from the internet, fishery management agencies, scientific organisations or other sources.

[sta_anchor id=”C1″]

COMPONENT 1: Target fish stocks

|

1A: Stock Status |

||

|

CRITERIA: (i)The stock is at a level which maintains high productivity and has a low probability of recruitment overfishing. |

||

|

(a) Stock Status |

LOW RISK |

|

|

Australian Sardine are a low trophic level (LTL) species, and this assessment considers the role of LTL species in the ecosystem. The South Australian Sardine Fishery harvests from the southern Australian stock. The majority of the catch from the southern Australian stock is taken from South Australia, with much smaller catches from Port Phillip Bay, Victoria. Assessment of the South Australian Sardine Fishery has involved annual and, more recently, biennial Daily Egg Production Method (DEPM) surveys, and population modelling based on spawning biomass estimates, catch and catch-at-age data. The most recent estimates of spawning biomass have been above 150,000 t, which is well above the limit reference point of 75,000 t identified in the management plan for the fishery (Ward et al 2016a). The limit reference point is based on Australian studies that explicitly consider the role of these low trophic levels species in the ecosystem. This evidence indicates that the biomass of this stock is unlikely to be recruitment overfished. The current exploitation rate is around 23 per cent (that is, 38 000 t landed from a minimum estimate of spawning biomass of approximately 166 000 t), which is well below the level considered safe for this species (33 per cent, Smith et al 2015). Accordingly, it appears highly likely that the stock is above the point where serious ecosystem impacts could occur and is fluctuating around a level consistent with ecosystem needs. |

||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|

|

1B: Harvest Strategy |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (i)There is a robust and precautionary harvest strategy in place. |

|||

|

(a) Harvest Strategy |

LOW RISK |

||

|

The harvest strategy is based on licence limitation (14 licence holders) with specifications for gear, and a Total Allowable Commercial Catch (TACC) that is managed spatially within zones. Access to the South Australian Sardine Fishery is provided through a licence for the Marine Scalefish Fishery (MSF) with a sardine net endorsement. The fishery is managed through an individual transferrable quota (ITQ) system with a total allowable commercial catch (TACC) set for each 12-month period. The net endorsement allows the licence holder to use a small-mesh (14-22 mm) purse seine net when fishing for marine scalefish. The harvest strategy takes into account the broader ecosystem role of the LTL species by setting a conservative TAC that is pre-determined from harvest control rules that consider the last estimated spawning biomass from surveys (e.g. Ward et al 2016a), and the allowable exploitation rate based on ecosystem studies for pelagic LTL species in Australia (Smith et al 2015). It also considers that the southern Australia stock of Australian Sardine is a shared stock (i.e. a small fishery exists in Port Phillip Bay, Victoria). There is no or negligible traditional or recreational catch. Also, the fishery is limited to shallow coastal waters by the efficiency of purse seines, whereas the stock is more widely distributed across the continental shelf and into Victoria. A compliance program is in effect that ensures the TACC is not exceeded. The TACC has changed on several occasions in recent years, in both total catch and spatial allocation, in response to changes observed in the stock informed by data collection. In 2016, two separate zones were permanently set for the fishery: a Gulf Zone and an Outside Zone (Ward et al 2016b). The harvest strategy in the management plan for the fishery determines the amount of the TACC that can be taken in the Gulf Zone based on length frequency data collected in the fishery (PIRSA 2014a). There is evidence that the harvest strategy is responsive to the state of the stock and the elements of the harvest strategy work together to maintain a productive fishery. |

|||

|

(b) Shark-finning |

|||

|

NA |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There are well defined and effective harvest control rules (HCRs) and tools in place. |

|||

|

(a) HCR Design and application |

LOW RISK |

||

|

Given the difficulties in reliably estimating total biomass for Australian Sardines, spawning biomass estimates based on field surveys using the DEPM technique are the preferred approach for determining stock status in South Australia (Ward et al 2016a). The South Australian Sardine Fishery Management Plan (PIRSA 2014a) documents TACC decision rules that are based on exploitation rates. The HCRs operate on a sliding scale based on the results of the spawning biomass survey, which is conducted every two years. A key principle of the system is that exploitation rates do not exceed 25%, which historical data from the fishery suggested was a conservative approach. For example, a 2015 Commonwealth study on four Australian small pelagic species (Jack Mackerel, Trachurus declivis, Redbait Emmelichthys nitidus, Blue Mackerel Scomber australasicus and Australian Sardine Sardinops sagax) using an Atlantis ecosystem model (Atlantis-SPF), demonstrated that none of the key higher trophic level species has a high dietary dependence on these species (Smith et al 2015). The modelling suggested that Equilibrium BMSY for these species ranged from about 30 to 35% of unfished levels, and as a result it was suggested that standard target levels of biomass for Commonwealth fisheries (i.e. B48%) be maintained. Smith et al (2015) determined that sustainable exploitation rates varied across most of the species and stocks studied. For Australian Sardines, a maximum exploitation rate of 33% was suggested as it was the median value to obtain B48%, with a less than 10% chance of being below B20%, based on surveys conducted every five years. Moreover, an ecosystem model on the South Australian Australian Sardine Fishery suggested that there were no key predators that were highly dependent on Australian Sardines as their primary food source (Goldsworthy et al 2011), which inferred that these levels of exploitation would also be safe for the ecosystem. Recently, the HCRs have been applied within spatial management zones to ensure a spread of the catch and to reduce the risk of localised depletion. Accordingly, well-defined HCRs and tools are in place that are robust to the main uncertainties and are expected to reduce exploitation as PRI is approached, and consistent with ecosystem needs. |

|||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

||

|

CRITERIA: (i) Relevant information is collected to support the harvest strategy. |

||||

|

(a) Range of information |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

There is a comprehensive suite of information available on the southern Australian stock of Australian Sardines. The biology of the species is well understood including the early life history, growth, diet, sexual maturity, fecundity, stock biomass and its variability, and trophic linkages within the ecosystem (summarised in Ward et al. 2016a). The fishery suffered two mass mortality events, one in 1995 and another in 1998. Spawning biomass was determined throughout the recovery of the fishery. Commercial logbook data are collected at relevant spatial and temporal scales to support the harvest strategy. There is no or negligible traditional or recreational catch. |

||||

|

(b) Monitoring and comprehensiveness |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Stock abundance is measured every two years from fishery independent surveys of the Daily Egg Production Method (DEPM). The DEPM survey is the main data source for the stock assessment and has been used to estimate the spawning biomass of Australian Sardines in South Australia since 1995 (PIRSA 2014a). All catches are monitored through the quota system. Abundance and removals are monitored at a level of accuracy and coverage consistent with the HCR. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is an adequate assessment of the stock status. |

||||

|

(a) Stock assessment |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The Daily Egg Production Method (Parker 1980, 1985; Lasker 1985), has been used to estimate the spawning biomass of Australian Sardine in South Australia since 1995. The DEPM was originally developed for stock assessment of northern anchovy off the west coast of North America (Parker 1980, 1985). The method relies on the premise that the spawning biomass of adults can be calculated by dividing the mean number of pelagic eggs produced per day throughout the spawning area. Total daily egg production is the product of mean daily egg production times the area. The key assumptions of the method are 1) that surveys are conducted during the main (peak) spawning season, 2) the entire area is sampled, 3) eggs are sampled without loss and estimated without error, 4) levels of egg production and mortality are consistent across the spawning area, and 5) representative samples of spawning adults are collected during the survey period (Ward et al. 2016a). The DEPM has been used for at least 15 species of small pelagic fishes, mainly clupeoids (Stratoudakis et al. 2006). The imprecision that characterises the DEPM is mainly associated with the estimation of total daily egg production. There are several key parameters in DEPM stock assessments that are estimated such as the spawning area, egg density and age, the proportion of females spawning, fecundity and sex ratio, which determine the precision of the biomass estimates and are influenced by the sampling intensity. While two reviews have concluded that DEPM is more suited to anchovy (Engraulidae spp.) rather than sardines (Clupidae spp.) (Alheit 1993, Startoudakis et al. 2006), the DEPM approach is appropriate for the stock and estimates status relative to reference points that are appropriate and can be estimated. |

||||

|

(b) Uncertainty and Peer review |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The stock assessment and the design of the fishery independent survey program considers all the uncertainties and assumptions associated with the DEPM approach (Ward et al., 2015a). These uncertainties have also been taken into consideration in the development of harvest control rules (PIRSA 2014a). The South Australian DEPM work has been published in peer-reviewed literature (e.g. Ward et al. 2010). A recent FRDC funded project established DEPM work in other parts of southern and eastern Australia (Ward et al, 2015b). This work included workshops to review the appropriateness of DEPM methods currently applied within Australia, to provide context to the best methods to apply for the other southern and eastern Australian pelagic stocks. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

[sta_anchor id=”C2″]COMPONENT 2: Environmental impact of fishing

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA aims to maintain other species above the point where recruitment would be impaired (PRI) and does not hinder recovery of other species if they are below the PRI. |

||

|

(a) Main other species stock status |

LOW RISK |

|

|

Of the families Engraulidae and Clupeidae, only Australian Sardines and Australian Anchovy (Engraulis australis) are listed in Schedule 1 of the Fisheries Management (MSF) Regulations as aquatic resources prescribed for the MSF. Therefore, under the current management arrangements the sardine net (the registered device) may only be used for the taking these species unless exempt under Section 115 of the Act. While bycatch data were historically gathered through an on-board observing program, there are no published data available to determine catch composition. A sizeable stock of Australian Anchovy occurs in South Australian waters (Dimmlich et al. 2004, Dimmlich et al. 2009), however Australian Anchovy are not targeted in South Australia as Australian Sardines are the preferred source for feeding the Southern Bluefin Tuna aquaculture industry. An ecological risk assessment was conducted that examined the risk to bycatch species that the fishery occasionally interacts with (PIRSA 2013). These species were rated negligible risk: Australian Anchovy, Blue Mackerel, Redbait, Jack Mackerel, Blue Sprat, and Sandy Sprat. These species were rated low risk: moray species, Blue Shark, Bronze Whaler, Snapper, barracuda (Sphyraena spp.), toadfish and cuttlefish (Sepia spp.). Despite a lack of ongoing data to accurately determine whether any non-target species would be considered as main other, the highly species-specific nature of the gear and the fishery methods, combined with the negligible risk rating for all non-target species determined by the management agency, provides sufficient confidence that the stock status of main other species can be assessed as low risk. |

||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to maintain or to not hinder rebuilding of other species; and the UoA regularly reviews and implements |

||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|

|

Australian Sardine is the dominant clupeid off South Australia, occurring from the southern parts of both gulfs to past the continental shelf (Ward et al. 2001). When Australian Sardine biomass is high, the Australian Anchovy occurs mainly in the northern gulfs, but when Australian Sardine biomass is low Australian Anchovies have the capacity to increase in abundance and expand their distribution into shelf waters (Ward et al. 2012). In 2000, DEPM surveys conducted for Australian Sardines were extended into the northern part of the Gulf St Vincent and Spencer Gulf so a spawning biomass estimate of Australian Anchovy could be completed (Dimmlich et al. 2009). The spawning biomass for Australian Anchovy in South Australian waters in 2000 was over 126,000 t (Dimmlich et al. 2009). This information was used to set a precautionary TACC for Australian Anchovy that should ensure, if targeting occurs, that the biomass will remain above the PRI for LTL species. The strategy for managing bycatch also includes an objective in the management plan to ensure that bycatch is monitored qualitatively through the on-board observer program. The strategy also includes regular updating of the ecological risk assessment so that if the profile of risk changes to any other retained species this can be identified and managed. Accordingly, while the position of the possible main other species against PRI is unknown, there appears to be an effective strategy in place to ensure the fishery does not hinder recovery if necessary. |

||

|

LOW RISK |

||

|

The work of Dimmlich et al. (2009) demonstrated that the DEPM approach worked well for Australian Anchovy. Given the very limited catches in the UoA and the effective management strategy employed for Australian Sardine, there is an objective basis for confidence that the same approach applied to Australian Anchovy would work just as effectively. |

||

|

(c) Shark-finning |

||

|

NA |

||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Information on the nature and amount of other species taken is adequate to determine the risk posed by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage other species. |

||

|

(a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|

|

On-board observer data have been used to determine bycatch composition, and this data has subsequently been used to determine risk to these individual species through the ecological risk assessment. All risks have been determined as low or negligible. A DEPM survey was conducted for Australian Anchovy (Dimmlich et al. 2009). Accordingly, quantitative information is available and is adequate to assess the impact of the UoA on non-target species and to detect any increase in risk. This information is sufficient to support a partial strategy where necessary. |

||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA meets national and international requirements for protection of ETP species. |

||||

|

(a) Effects of the UoA on populations/stocks |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The South Australian Sardine Fishery interacts with a number of ETP species including Short-beaked Common Dolphins (dolphin), Australian Fur Seals, New Zealand Fur Seal, Australian Sea Lions, White Shark, seabirds and syngnathids. The latter three species are rare events and mortality has not been reported (Mackay 2017). Seals and Sea Lions do interact with the gear but they are able to travel in and out of the nets at will over the floatline. Only one seal mortality has been recorded in the fishery’s history (Mackay 2017). The principal interactions are with dolphins and a specific report on dolphin interactions is published annually (Ward et al. 2015c and Mackay and Goldsworthy 2016). The fishery was closed for two months in 2005 because of high levels of encirclement and mortality of the Short-beaked Common Dolphin (Delphinus delphis). Following the development of an industry Code of Practice (latest version SASIA 2015), the levels of interactions have been substantially reduced (Ward et al. 2015c; Mackay 2017). There is still a considerable difference between reporting rates of dolphin interactions and mortalities between net sets with and without an independent observer which was highlighted in the recent re-assessment of the fishery by the Commonwealth Government for export exemption (DEE 2016). For example, in 2015/16 observers monitored almost 10.6% of net sets of which there was 31 dolphins encircled and one mortality. Logbook data for all 87 net sets recorded 164 encirclements and one mortality. Common dolphins are a protected species, not threatened or endangered. The ecological risk assessment assessed the biological risk to the dolphin population as negligible (PIRSA 2013). This assessment included input from all stakeholders including ENGOs. The industry has demonstrated significant improvement in reducing the mortality of dolphins to levels deemed acceptable by all stakeholders, albeit they maintain a target of zero dolphin mortalities. Current observer coverage is set at 10% of net sets for the fishery which the most recent analysis shows is representative of fishing operations. As there are no other major sources of dolphin mortality in South Australian fisheries (Tsolos and Boyle 2014; Mackay 2017), it is considered that the mortality is known and the direct effects of the UoA are highly unlikely to hinder recovery. Accordingly, this SI is assessed as low risk. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The UoA has in place precautionary management strategies designed to:

Also, the UoA regularly reviews and implements measures, as appropriate, to minimise the mortality of ETP species |

||||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

There is an effective management strategy in place to manage dolphin and other ETP interactions. The strategy includes limited licences, ITQs for the target species, an independent observer program specifically for ETP interactions, a commercial logbook program for ETP species, ecological risk assessments, and an industry Code of Practice. The Threatened, Endangered or Protected Species Code of Practice was developed during the closure period that outlined procedures for avoiding encirclements and releasing encircled animals. Interaction rates decreased significantly following the introduction of the code of practice (Hamer et al. 2008, 2009, Mackay 2017). A working group that includes industry, fisheries managers, scientists and representatives of conservation agencies meets every quarter to review logbook and observer data, and assess the effectiveness of the Code of Practice in reducing interaction rates. A report on interaction rates and the effectiveness of the Code of Practice is published annually (Ward et al. 2015c). This comprehensive strategy should ensure that the fishery minimises interaction levels. |

||||

|

(b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

Ward et al. (2013, 2015c) documents the reduction in ETP interactions and mortalities through the industry Code of Practice. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the program, Hamer et al. (2009) reported that “in 2007-08 observers monitored 200 of the 884 net-sets in the South Australian Sardine Fishery (22.6% coverage). A total of 79 common dolphins were encircled (0.395 per net-set) in 27 encirclement events. Eleven dolphins died (0.055 per net-set) in eight mortality events. In 2012/13 the rates of interactions and mortalities reduced to 0.321 and 0.012, respectively, while in 2015/16 the rate of interactions was the lowest recorded (Mackay et al 2017). Moreover, the ecological risk assessment assessed the biological risk to the dolphin population as negligible (PIRSA 2013). These data provide an objective basis for confidence that the strategy will work and is being implemented successfully. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Relevant information is collected to support the management of UoA impacts on ETP species, including:

|

||||

|

(a) Information |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The observer program and commercial ETP logbook (notwithstanding weaknesses in reporting) provide representative, quantitative information that has been demonstrated as adequate to assess UoA-related mortality and support a strategy to manage impacts. |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to habitat structure and function, considered on the basis of the area(s) covered by the governance body(s) responsible for fisheries management |

||||||

|

(a) Habitat status |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Examples of “serious or irreversible harm” to habitats include the loss (extinction) of habitat types, depletion of key habitat forming species or associated species to the extent that they meet criteria for high risk of extinction, and significant alteration of habitat cover/mosaic that causes major change in the structure or diversity of the associated species assemblages (MSC, 2014). Purse seine nets are pelagic in nature, with no interaction with sea floor habitats during normal operations in most fisheries. In South Australia, fishing operations avoid rough bottom and are conducted on generally smooth substrate (PIRSA 2013). Also, it is undesirable for the net to touch the sea floor as it can cause damage to the net and ‘roll up’ the net, where the bridles and net twist around the purse wire (PIRSA 2013). The nets used on the fishery are light and cause minimal damage to habitats contacted (e.g. seagrass) when this occurs. Overall, the intensity of the disturbance is likely to be minor and measured at the scale of metres. (DEE 2016) concluded that “due to the low impact harvesting method used in the fishery (purse seining), impacts to the physical ecosystem such as the ancient coastline, are negligible”. Accordingly, the fishery is highly unlikely to reduce habitat structure and function to a point where there would be serious or irreversible harm. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There is a strategy in place that is designed to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to the habitats. |

||||||

|

(a) Management strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

There is a partial strategy in place to ensure that the fishery does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to habitat types, including limited entry, catch and effort limits, gear restrictions, spatial restrictions and closures. The nature of the gear type which is fished at the surface of the water column provides an objective for confidence that the partial strategy will work. |

||||||

|

(b) Management strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

There is evidence through compliance monitoring and observer coverage that the partial strategy is being implemented successfully. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Information is adequate to determine the risk posed to the habitat by the UoA and the effectiveness of the strategy to manage impacts on the habitat. |

||||||

|

(a) Information quality |

MEDIUM RISK |

|||||

|

There is considerable habitat mapping that has been conducted in South Australian waters (e.g. see Nature Maps, accessed at https://data.environment.sa.gov.au/NatureMaps/Pages/default.aspx), however much of it has been in shallow waters or in regions not targeted by the purse seine fishery. Despite this, the nature of the habitats fished are broadly understood. Where interactions with the bottom do occur, fishers avoid rugose habitats to avoid gear damage. |

||||||

|

(b) Information and monitoring adequacy |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Given the pelagic nature of the gear type, the available habitat information is adequate to allow for the identification of the main impacts on the main habitat types and to detect increased risk. There is good information on the spatial extent of interaction and the timing and location of use of the fishing gear. |

||||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The UoA does not cause serious or irreversible harm to the key elements of ecosystem structure and function. |

|||||

|

(i)(a) Ecosystem Status |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

Serious or irreversible harm in the ecosystem context should be interpreted in relation to the capacity of the ecosystem to deliver ecosystem services (MSC, 2014). Examples include trophic cascades, severely truncated size composition of the ecological community, gross changes in species diversity of the ecological community, or changes in genetic diversity of species caused by selective fishing. Goldsworthy et al. (2011) conducted an extensive study of the trophodynamics of the eastern Great Australian Bight to determine the ecological effects of harvesting Australian Sardines from the fishery. The authors determined that current levels of fishing effort are not impacting negatively on the ecosystem function (Goldsworthy et al. 2011). No predatory species feeds exclusively or even predominately on Australian Sardine, therefore there are no obligate Australian Sardine predators (they are all opportunistic). Food availability is not negatively impacting on the foraging behaviour or reproductive success of any predatory species. A separate, fishery-specific study of four Commonwealth pelagic species aimed to determine sustainable harvest levels in an ecological context (Smith et al 2015). This study confirmed the results of Goldsworthy et al (2011), and suggested that compared to several northern hemisphere systems (Smith et al 2011), Australian key predators are not highly reliant on these pelagic fishes. This directly confirmed that the conservative exploitation rates maintained within the harvest strategy are highly unlikely to impact the ecosystem in a serious or irreversible manner. The Commonwealth Government recently reviewed the fishery for EPBC export exemption (DEE 2016) stating “fishing activity is closely linked to the remaining relevant key ecological features of regional upwellings and small pelagic fish aggregations, however impacts on the food web are unlikely given that take of the target species is limited to ecologically sustainable levels, as prescribed in the fishery’s management plan. Incidental impacts of the fishery bycatch species are minimised through specific industry practices to avoid these species, such as through the Code of Practice for mitigating of interactions of the South Australian Sardine Fishery with wildlife (SASIA 2015).” Based on all of the above, the UoA is highly unlikely to disrupt the key elements underlying ecosystem structure and function to a point where there would be a serious or irreversible harm. |

|||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) There are measures in place to ensure the UoA does not pose a risk of serious or irreversible harm to ecosystem structure and function. |

|||||

|

(a) Management Strategy in place |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

The main measures in place to mitigate ecosystem impacts include the use of a benign gear type, a limitation on licences and a TACC that is based on conservative exploitation rates linked to robust measures of spawning biomass for the fishery. The HCRs account for the low trophic level of the species to ensure that the fishery does not disrupt structure and function of the ecosystem. Dedicated studies have been undertaken to assess the potential trophodynamic impacts of the fishery, and management measures have been introduced to limit impacts on key ecosystem components (e.g. ETPs). These measures are likely to constitute at least a partial strategy which could be expected to restrain the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem so as to achieve the outcomes stated in criterion 2D(i). |

|||||

|

(b) Management Strategy implementation |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

There is clear and objective evidence that the partial strategy is being implemented successfully through the compliance program. The research of Goldsworthy et al. (2011) and Smith et al (2015) provide objective, scientific evidence that the strategy is working. |

|||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) There is adequate knowledge of the impacts of the UoA on the ecosystem. |

|||||

|

(a) Information quality |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

The trophodynamic work of Goldsworthy et al. (2011) builds on population monitoring data that is routinely collected for a number of the key predators in South Australia, including Australian and New Zealand Fur Seals, Australian Sea Lions, and sea birds. Additionally, the research of Smith et al (2015) provides a direct and relevant measure of the validity of exploitation rates with respect to the ecosystem impacts. This high-quality information, together with ongoing information from the fishery on catch, SpB and interactions with non-target species, is sufficient to detect increased risk. |

|||||

|

(b) Investigations of UoA impacts |

LOW RISK |

||||

|

The main impacts of the UoA on key ecosystem elements can be inferred from existing information, and Goldsworthy et al. (2011) represents a detailed study on the ecosystem impacts of the removal of Australian Sardines from the South Australian ecosystem. |

|||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

||||

[sta_anchor id=”C3″]COMPONENT 3: Management system

|

CRITERIA: (i) The management system exists within an appropriate and effective legal and/or customary framework which ensures that it:

|

||||

|

(a) Compatibility of laws or standards with effective management |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The South Australian Fisheries Management Act 2007, the Offshore Constitutional Settlement (OCS) between South Australia and the Australian Commonwealth and the “Management Plan for the South Australian Commercial Marine Scalefish Fishery Part B – Management arrangements for the taking of Australian Sardines” (PIRSA 2013) provide the basis for an effective legal system that can deliver the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2. |

||||

|

(b) Respect for Rights |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The Fisheries Act (2007) develops explicit access rights by way of allocation for aboriginal people. The Australian Sardine Management Plan (PIRSA 2014a) has currently allocated 100% of the Australian Sardine rights to commercial fishers as the recreational catch is negligible and it is understood that traditional fishing did not occur. The allocation policy has mechanisms for changing these allocations if new information arises. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The management system has effective consultation processes that are open to interested and affected parties. The roles and responsibilities of organisations and individuals who are involved in the management process are clear and understood by all relevant parties. |

||||

|

(a) Roles and Responsibilities |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The roles and responsibilities of the main people (e.g. Minister for Agriculture, Food and Fisheries, Primary Industries and Regions South Australia (PIRSA) Chief Executive) and organisations (South Australian Sardine Industry Association, SASIA) involved in the South Australian fisheries management process are well-understood, with relationships and key powers explicitly defined in legislation (e.g. Fisheries Act 2007, Fisheries Management (Marine Scalefish Fisheries) Regulations 2006). The state authority (PIRSA Fisheries) manages the day to day business of fishery management and provides key advice to the Minister. |

||||

|

(b) Consultation Process |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

While some consultation occurs directly with license holders on operational issues, most consultation occurs through the peak industry body the South Australian Sardine Industry Association (SASIA). PIRSA Fisheries conduct most of the day to day management and consultation processes for the fishery. Specific working groups are established where needed, such as the Wildlife Working Group that meets every three months to review the data and discuss issues regarding the fishery’s interaction with dolphins. The existing system for consultation includes both statutory and non-statutory opportunities for interested stakeholders to be involved in the management system. Opportunities for stakeholder input into processes such as the development of Management Plans are provided through public consultation periods, or involvement in working groups. |

||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) The management policy has clear long-term objectives to guide decision making that are consistent with MSC fisheries standard, and incorporates the precautionary approach. |

||||

|

(a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

The Fisheries Management Act 2007 has clearly-defined long-term management goals that are consistent with the precautionary principle. The principal object of the Act is “to protect, manage, use and develop the aquatic resources of the State in a manner that is consistent with ecologically sustainable development”. The first principle of this object is “proper conservation and management measures are to be implemented to protect the aquatic resources of the State from over-exploitation and ensure that those resources are not endangered”. While a number of other principles follow this regarding how best to use and manage the resource, object 2 states “The principle set out in subsection (1)(a) (i.e. above) has priority over the other principles”. The Act also explicitly references the precautionary approach as part of the concept of ecologically sustainable development. Part 2(7)(5) notes that ESD should be pursued “taking into account the principle that if there are threats of serious or irreversible damage to the aquatic resources of the State, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent such damage.” |

||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||

|

3B: Fishery Specific Management System |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (i) The fishery specific management system has clear, specific objectives designed to achieve the outcomes expressed by Components 1 and 2. |

||||||

|

(a) Objectives |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

There are short and long term fishery-specific objectives listed in the management plan (PIRSA 2013) that are consistent with both Components 1 and 2. The overarching objectives state: 1) Maintain ecologically sustainable Australian Sardine biomass, and 2) Protect and conserve aquatic resources, habitats and ecosystems. Underneath these objectives are a series of operational objectives and performance measures specific to the fishery to achieve these objectives. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (ii) The fishery specific management system includes effective decision making processes that result in measures and strategies to achieve the objectives and has an appropriate approach to actual disputes in the fishery. |

||||||

|

(a) Decision making |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The fishery responds to both serious and less serious issues in a manner consistent with a low risk score for this SI. For example, the response to the mortality of dolphins demonstrated that government were willing to act swiftly to address a serious issue by a 2-month closure, and industry and researchers combined to develop a code of best practice that has substantially reduced the frequency of mortality events. Of a less serious nature, recent data suggested that the size structure of Australian Sardines in the main catching area were of sub-optimal size. In response, the spatial allocation of the catch was altered to protect the smaller Australian Sardines by shifting effort to more remote areas where Australian Sardines were of a larger size. |

||||||

|

(b) Use of the Precautionary approach |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Both of these examples above demonstrate application of the precautionary principle. Of particular importance, the Ministerial decision to close the fishery immediately upon learning of the dolphin mortality issues demonstrated a clear precautionary approach. |

||||||

|

(c) Accountability and Transparency |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Information on the biological performance of the fishery is provided in the SARDI stock assessment reports. Economic reports provide public information on the economic performance of the fishery and includes broader social measures. Reports on ETP interactions are provided in the SARDI ETP annual report (e.g. Mackay 2017). Other issues relevant to the daily management of the fishery are discussed with licence holders (through SASIA) at regular and ad-hoc Management Committee meetings as required. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iii) Monitoring, control and surveillance mechanisms ensure the management measures in the fishery are enforced and complied with. |

||||||

|

(a) MCS Implementation |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

PIRSA runs a compliance program that has dual objectives (PIRSA 2013):

These objectives are consistent with the National Fisheries Compliance Policy. PIRSA maximises voluntary compliance by ensuring that fishers are aware of the rules that apply to their fishing activities, that they understand the rules and the purpose of those rules, and that they operate in a culture of compliance. PIRSA creates effective deterrence through the presence of fisheries officers and the visibility of compliance operations, as well as through detection and prosecution of illegal activity. The objectives are prioritised through a 3-year planning cycle that is underpinned by an annual compliance risk assessment. Through this process key risks are identified, responses are planned, and benchmarks are established to monitor effectiveness. Based on these actions, an annual compliance status report is provided to industry at the end of each quota year. |

||||||

|

(b) Sanctions and Compliance |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

The Fisheries Act 2007 provides the legislative framework for fisheries sanctions and compliance in South Australia. The Act defines offences, enforcement, and review and appeals. Fishery specific legislation (e.g. Fisheries Management (Marine Scalefish Fisheries) Regulations 2006) further defines the sanctions and compliance for the fishery. Fishers are generally thought to comply with the management system, including providing information important to the effective management of the fishery, and there is some evidence of improved compliance with ETP species interactions. For example, PIRSA (2014b) report that “in response to discrepancies between observer and industry reported dolphin interactions, the SASIA developed a process of real-time reporting on interactions to help improve transparency and remove discrepancy between interaction rates. There has been a subsequent decrease in the difference between reported interaction rates indicating that this industry-led initiative has improved transparency of reporting frameworks.” |

||||||

|

LOW RISK |

||||||

|

The compliance system is incentive based and encourages voluntary industry compliance including the provision of intelligence, which in turn reduces the risk of systematic non-compliance. Risk issues are identified and addressed annually so that the risk of non-compliance issues becoming systematic is minimal. |

||||||

|

CRITERIA: (iv) There is a system for monitoring and evaluating the performance of the fishery specific management system against its objectives. |

||||||

|

(a) Evaluation coverage |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

PIRSA has a number of processes in place to evaluate key parts of the management system, including the effectiveness of its target species harvest control arrangements, arrangements to mitigate unacceptable ecological risks, and compliance with management arrangements. The effectiveness of commercial and recreational management arrangements is primarily monitored through commercial catch and effort returns and periodic recreational fishing surveys, and reported against through the Stock Assessment reports. Effectiveness of non-target species management arrangements are evaluated through ecological risk assessment (PIRSA 2013). The effectiveness of the compliance regime is evaluated through annual compliance risk assessments and an annual compliance report. |

||||||

|

(b) Internal and/or external review |

LOW RISK |

|||||

|

Internal review of the management system occurs through the periodic review of the Management Plan every 5 years. The Management Plan is prepared by PIRSA in consultation with stakeholders, and was approved by the now defunct Fisheries Council comprised of a panel of independent experts, prior to being approved by the Minister and Cabinet. Periodic external review of the fishery has also occurred through the Commonwealth EPBC export accreditation process. External reviews of the stock assessment reports do occur occasionally. |

||||||

|

PI SCORE |

LOW RISK |

|||||

Alheit, J. (1993). Use of the daily egg production method for estimating biomass of clupeoid fishes: A review and evaluation. Bulletin of Marine Science. 53(2): 750-767.

DEE (2016) Assessment of the South Australian Sardine Fishery. https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/72da29f4-befd-40a5-baa5-f21abe509e04/files/sa-Australian Sardine-fishery-assessment-report-2016.pdf

Dimmlich, WF, Breed, WG, Geddes, M and Ward, TM (2004) ‘Relative importance of gulf and shelf waters for spawning and recruitment of Australian anchovy, Engraulis australis, in South Australia’, Fisheries Oceanography, 13 (5), pp.310-323.

Dimmlich, WF, Ward, TM and Breed, WG (2009) ‘Spawning dynamics and biomass estimates of an anchovy Engraulis australis population in contrasting gulf and shelf environments’, Journal of Fish Biology, 75, pp.1560-1576.

Goldsworthy, S.D., Page, B, Rogers, RP & Ward, T. (2011) Established ecosystem –based management for the South Australian Sardine Fishery: developing ecological performance indicators and reference points to assess the need for ecological allocations. Final Report to the FRDC SARDI (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2010/000863-1. SARDI Report Series No. 529 173 pp.

Hamer, DJ, Ward, TM & McGarvey, R (2008) Measurement, management and mitigation of operational interactions between the South Australian Sardine Fishery and Short-beaked Common Dolphins (Delphinus delphis), Biological Conservation, 141: 2865–2878.

Hamer, D.J., A. Ivey, and T.M. Ward (2009). Operational interactions of the South Australian Sardine Fishery with the Common Dolphin: November 2004 to March 2009. SARDI Aquatic Sciences Publication No. F2007/001098-2. SARDI Research Report Series No. 354.

Lasker, R. (1985). An egg production method for estimating spawning biomass of pelagic fish: application to northern anchovy, Engraulis mordax. NOAA. Tech. Rep. NMFS, 36: 1-99.

Mackay, A.I. and Goldsworthy, S.D (2016). Mitigating operational interactions with short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis): application of the South Australian Sardine Fishery Industry Code of Practice 2015-16. Report to PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2010/000726-7. SARDI Research Report Series No. 934. 38pp.

Mackay, A.I. (2017). Operational interactions with Threatened, Endangered or Protected Species in South Australian Managed Fisheries Data Summary: 2007/08 –2015/16. Report to PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2009/000544-7. SARDI Research Report Series No. 945. 74pp.

Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) (2014) MSC Fisheries Certification Requirements and Guidance. Version 2.0, 1st October, 2014.

Parker, K. (1980). A direct method for estimating northern anchovy, Engraulis mordax, spawning biomass. Fisheries Bulletin. (US). 541-544.

Parker, K. (1985). Biomass model for the egg production method. In: An egg production method for estimating spawning biomass of pelagic fish: application to northern anchovy, Engraulis mordax. NOAA. Tech. Rep. NMFS, 36: 5-6.

PIRSA (2013). ESD risk assessment of South Australia’s Sardine Fishery. Accessed at: (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/68608772-df30-455e-9aa9-379ed843eb33/files/sa-Australian Sardine-fishery-draft-esd.pdf)

PIRSA (2014a). Management Plan for the South Australian Commercial Marine Scalefish Fishery Part B –Management Arrangements for the Taking of Sardines.

PIRSA (2014b). Ecological Assessment of the South Australian Sardine (Sardinops sagax) Fishery. Reassessment Report.27pp.

SASIA (2015) Code of practice for mitigation of interactions of the South Australian Sardine Fishery with threatened, endangered, and protected species, South Australian Sardine Industry Association, Port Lincoln, www.saAustralian Sardines.com.au/links-resources.html.

Smith, A.D., Brown, C.J., Bulman, C.M., Fulton, E.A., Johnson, P., Kaplan, I.C., Lozano-Montes, H., Mackinson, S., Marzloff, M., Shannon, L.J., Shin, Y.J. and Tam, J. (2011). Impacts of fishing low-trophic level species on marine ecosystems. Science. 334(6052):39.

Smith ADM., Ward, TM., Hurtado, F., Klaer, N., Fulton, E., and Punt, AE (2015), Review and update of harvest strategy settings for the Commonwealth Small Pelagic Fishery – Single species and ecosystem considerations. Hobart. Final Report of FRDC Project No. 2013/028.

Stratoudakis, Y., Bernal, M., Ganias, K, and Uriate, A. (2006). The daily egg production method: recent advances, current applications and future challenges. Fish and Fisheries, 7: 35-57.

Tsolos and Boyle (2014) Interactions with Threatened, Endangered or Protected Species in South Australian Managed Fisheries 2012/13. http://www.sardi.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/220092/Wildlife_Interactions_in_SA_Fisheries_2013_-_FINAL.pdf

Ward T.M., Hoedt F., McLeay L.J., Dimmlich W.F., Jackson M., Rogers P.J., and Jones K. (2001). Have recent mass mortalities of the pilchard Sardinops sagax facilitated an expansion in the distribution and abundance of the anchovy Engraulis australis in South Australia? Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 220: 241-251.

Ward, TM, Paul Burch, Lachlan J. McLeay & Alex R. Ivey (2010). Use of the Daily Egg Production Method for Stock Assessment of Sardine, Sardinops sagax; Lessons Learned over a Decade of Application off Southern Australia. Reviews in Fisheries Science. Volume 19, Issue 1, 2011.

Ward, TM, Burch, P and Ivey, AR (2012) South Australian Sardine (Sardinops sagax) Fishery: stock assessment report 2012, SARDI publication no. F2007/000765-4, SARDI Research Report Series no.667, South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide.

Ward T. M., Whitten, A.R. and Ivey, A.R. (2015a). South Australian Sardine (Sardinops sagax) Fishery: Stock Assessment Report 2015. Report to PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2007/000765-5. SARDI Research Report Series No. 877. 103pp.

Ward, T. M., Burnell, O., Ivey, A., Carroll, J., Keane, J., Lyle, J. and Sexton, S. (2015b). Summer spawning patterns and preliminary daily egg production method survey of Jack mackerel and Sardine off the East Coast. 64pp.

Ward, T. M., Ivey, A. and Carroll, J. (2015c). Effectiveness of an industry Code of Practice in mitigating the operational interactions of the South Australian Sardine Fishery with the short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis). Report to PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture (PDF 1.9 MB). South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2010/000726-6. SARDI Research Report Series No. 876. 35pp.

Ward, T.M., Ivey, A.R. and Carroll, J.D. (2016a). Spawning biomass of Sardine, Sardinops sagax in waters off South Australia in 2016. Report to PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2007/000566-7. SARDI Research Report Series No. 931. 31pp.

Ward, T., Moore, A., Andrews, J., Norriss, J. and Stewart, J. (2016b). Australian Sardine, Sardinops sagax. in Carolyn Stewardson, James Andrews, Crispian Ashby, Malcolm Haddon , Klaas Hartmann, Patrick Hone, Peter Horvat, Stephen Mayfield, Anthony Roelofs, Keith Sainsbury, Thor Saunder s, John Stewart, Ilona Stobutzki and Brent Wise (eds) 2016, Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2016, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.